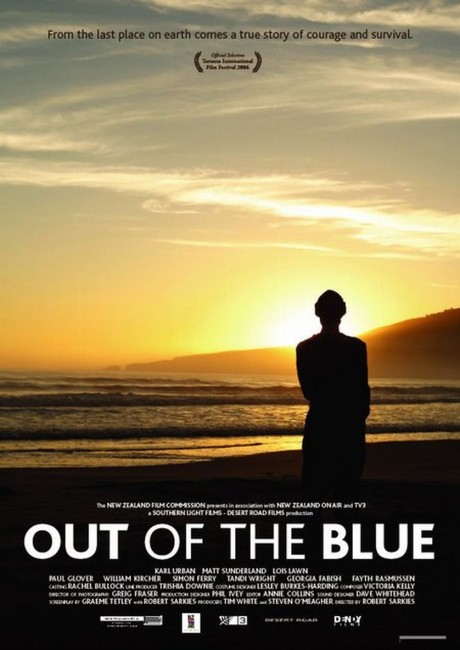

New Zealand. 2006.

Crew

Director – Robert Sarkies, Screenplay – Robert Sarkies & Graham Tetley, Based on the Book Aramoana: 22 Hours of Terror by Bill O’Brien, Producers – Steven O’Meagher & Tim White, Photography – Greig Fraser, Music – Victoria Kelly, Visual Effects Supervisor – George Port, Production Design – Phil Ivey. Production Company – The New Zealand Film Commission/NZ On Air/TV3/Southern Light Films/Desert Road Films.

Cast

Karl Urban (Nick Harvey), Matt Sunderland (David Gray), Lois Lawn (Helen Dickson), William Kircher (Stu Guthrie), Simon Ferry (Gary Holden), Tandi Wright (Julie Anne Bryson), Vanessa Stacey (Vanessa Percy), Bruce Phillips (Chris Cole), Fayth Rasmussen (Stacey Percy), Timothy Bartlett (Jimmy Dickson), Paul Glover (Paul Knox), Georgia Fabish (Chiquita Holden), Danaka Wheeler (Jasmine Holden), Dra McKay (Heather Dickson)

Plot

November 13, 1990 in the tiny New Zealand town of Aramoana. Angry when a neighbouring child runs across his property, David Gray, a reclusive unemployed man who collects guns, takes one of his rifle and shoots the boy’s father. Gray then bursts into the family’s house, shoots at the children and sets the house on fire. The town slowly awakens to panic as Gray runs rampant, shooting at the locals. The nearby police Armed Defenders squad are rushed to Aramoana and hunt through the town during the night to try to bring Gray down, whilst the residents huddle in fear inside their homes.

As a New Zealander, I remember turning on the news one evening and suddenly seeing coverage from Aramoana – a tiny town in the South Island not far from Dunedin that has a population of only around 200 and which most New Zealanders couldn’t even place it on a map – where the Armed Defenders Squad (the equivalent of a US SWAT team) were holding off against an armed gunman. Over November 13-14 of 1990, David Gray, a reclusive unemployed local, went on a shooting spree after an argument with a neighbour erupted. Throughout the night, Gray ran rampant through the township shooting as locals cowered in their houses. Gray killed a total of thirteen people before he was eventually shot by the Armed Defenders the following day. The situation held considerable shock value for a placid country like New Zealand where private gun control is strictly enforced, where the annual murder rate rarely ever rises to a number that be counted on more than two hands and not even the police carry firearms. The events of November 13-14 1990 served to put Aramoana onto the map and Aramoana has since become a word that will always be associated in infamy with the David Gray shootings.

Out of the Blue joins a swathe of true-life crime films that have come out in recent years – the likes of Dahmer (2002), Ted Bundy (2002), Gacy (2003), Monster (2003), Wonderland (2003), The Hillside Strangler (2004), Karla (2006), Chapter 27 (2007) etc. Although if there is any film that Out of the Blue resembles it is surely the one other Kiwi film about a true life murderer Bad Blood (1982), which was based on the story of Stanley Graham who went on a killing spree on New Zealand’s West Coast during the 1940s. Both Stanley Graham and David Gray were recluses and gun obsessives who went on shooting sprees after snapping over a trivial incident. Graham and David Gray even look the same, hunched into rolled-up balaclavas.

However, Out of the Blue is quite a different film from these others true crime stories. Most of these other abovementioned films evoke their story as a true crime expose, sketching out the events as they transpire or speculatively venturing into the subject’s psychopathology. Like one other New Zealand true crime story, Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures (1994), Out of the Blue is a film that seems as much about the environment where the shootings take place as the events themselves.

Both Jackson and director Robert Sarkies set their films at direct contrast to the ordinariness of calm, docile New Zealand at a particular time and place. Aramoana is seen as an utterly placid town where the pace of life takes place at a crawl, where children play in the streets without any worry of vehicles coming by and when shots ring around, locals look around with curious puzzlement and take some time to ever think of any notion of danger.

Cinematographer Greig Fraser offers up some exquisite shots of the beaches and peninsula, the spit stretching out into the bay, the bush surrounding the town – all of which has an extraordinary calmness and serenity that stands at direct contrast to the events of the film. Elsewhere Robert Sarkies conjures a distinctly Kiwi (and at times almost nostalgic) rural world of baches (of course making sure to get the Southland colloquial distinction between a bach and a crib), summer barbeques, Marmite on the breakfast table, dads in pairs of shorts two sizes too small and the days of red telephone boxes. Not to mention a soundtrack made up of tracks from classic 1980s New Zealand groups like Th’ Dudes, Coconut Rough and The Chills.

In this respect, Robert Sarkies’ approach to Out of the Blue is as far away from Hollywood dramatic effect as could be. The film is entirely one of understatement – the first killing when it comes jolts the audience in its casualness and lack of pumped-up drama. Despite such a low-key and unmelodramatic approach, Sarkies manages to generate considerable tension in the lurking around the town trying to catch Gray. One minor complaint that one might make is that the film never delves much into the psychology of David Gray. We get a few almost cliché shots where Sarkies attempts to depict Gray’s madness with fractured, chaotic camera-work or show Gray huddled up in his home obsessively studying gun magazines, and an earlier scene that acts as prologue to the main action where he loses his cool in a bank because of unnecessary fees. (I know the feeling).

The nearest Out of the Blue comes anywhere near attempting to be a Hollywood film is in the casting of Karl Urban who subsequently became a big name talent on the international stage. Urban has clearly been cast with an eye towards leading man heroism, although this feels somewhat awkward in Out of the Blue – as though the film is trying to create the role because it feels it needs to. Alas, in Robert Sarkies conducting such a rigorously accurate telling of the events, Karl Urban has ended up filling the role in a way that gives the part more expectation than it ends up getting. For example, with the type of role that Urban is filling, one would have at least expected him to be one of the police present during the climactic shooting of Gray, but in fact he is shuffled offstage, escorting one of the kids out of the town, several scenes earlier.

One can clearly see that Robert Sarkies’ real interest in Out of the Blue is in crafting a tribute to the heroism of the people involved. The end credits come with a list of dedications, which include a roll of the names of the dead, as well as the officers and citizens who received medals and commendations. It is this one suspects that is Robert Sarkies’ real interest – making a film about the heroism of ordinary people in horrific circumstances. The standout performance of the film comes from the unknown Lois Lawn, who is simply marvellous in her incarnation of a bygone generation of Wartime-era Kiwis who, after having lost her crutches, matter-of-factly crawls back and forth between her house and the road to get help for a wounded victim.

Robert Sarkies has made a painstaking effort to replicate the detail of the Aramoana massacre. He and co-writer Graham Tetley went and rented a cottage in the Aramaona township and invited locals to come and tell their stories and then composited these into the events of the film – in comparison, a film like Karla had to go and shoot in another entire country because of local oppostion to the idea of the film. You could almost guarantee that Monster, Ted Bundy et al would never have had such a user-friendly and respectful way of researching the material. Unlike most of the other films in the true life crime genre, Sarkies and Tetley go to the extent of naming all the characters after the real-life figures. The film was able to shoot in Aramoana itself, although due to the tender sensitivity of the incident in recent memory, the bulk of it was shot in Long Beach a few miles away from Aramoana.

(Nominee for Best Cinematography at this site’s Best of 2006 Awards).

Trailer here