New Zealand. 2003.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Gaylene Preston, Producers – Gaylene Preston & Robin Laing, Photography – Alun Bollinger, Music – Plan 9, Visual Effects – WETA Digital, Special Effects Supervisor – Daryl Richards, Makeup Effects – WETA Workshop (Supervisor – Richard Taylor), Production Design – Joe Bleakley. Production Company – Gaylene Preston Productions/Huntaway Productions/New Zealand Film Production Fund/The New Zealand Film Commission/NZ On Air/TVNZ

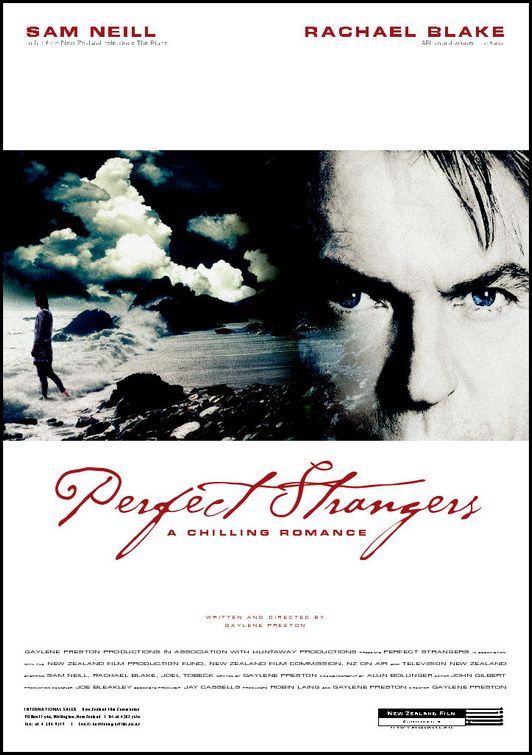

Cast

Rachael Blake (Mel), Sam Neill (The Man), Joel Toebeck (Bill)

Plot

Mel works at a fish’n’chip shop in the small town of Buller on New Zealand’s West Coast. One night she meets a handsome stranger in the local pub and, while drunk, agrees to go home with him for the night. When she comes around, she finds herself on his fishing boat as he takes her to the remote island he calls home. Once there, he insists that he is in love with her, despite her protests that he does not know her. He then makes her his prisoner. She attempts to make an escape but he is injured during the attempt. She nurses him back to health and an attraction grows between the two of them. He grows worse and so she decides to take him back to the mainland, only for the boat to be overturned during a storm. She swims ashore to find his dead body on the beach. She carries the body back to the hut and places it in the deep freezer. She is then surprised when the stranger appears to her at night and they become lovers. However, their love is threatened when the real owner of the island, a fisherman Bill and a former boyfriend of hers, arrive.

Perfect Strangers is a thriller from New Zealander Gaylene Preston. Two decades earlier, Preston made her directorial debut with the stalker film Mr Wrong (1985), entitled Dark of the Night in the US. Since then Preston has maintained a modest directorial career (if one that has never extended much outside of New Zealand) with films like the comedy Ruby and Rata (1990); Bread and Roses (1994), a biopic of Sonja Davies, an early New Zealand health campaigner and feminist; the documentary War Stories (1995) in which various women from Preston’s mother’s generation recounted their experience of World War II; and the tv mini-series Hope and Wire (2014) about the Christchurch Earthquake. All of Preston’s films have a strong interest in women’s issues.

Mr Wrong was a thriller about a woman who buys a car that may be haunted and at the same time finds herself stalked by a sinister stranger. There are many similarities between it and Perfect Strangers. In both films, the central character is a woman who is in peril (being stalked, being abducted) from sinister men; both films also sit in an uncertain place between whether the sinister male (who in both films is simply called The Man) is real or ghostly. Both films also have clear feminist sympathies – here Preston laces her abduction tale with all sorts of sardonic allusions to fairytales – with references to “a dark and stormy night,” Sam Neill calling the batch on the island ‘his castle’, and where Neill and Rachael Blake’s love does literally become “happily ever after.”

Perfect Strangers starts out like a standard woman abducted thriller and travels along similar lines to films such as The Collector (1965), Pedro Almodovar’s Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down (1990), Boxing Helena (1993), The Maddening (1995) and Paranoid (2000). Here Preston does a fair, if never entirely standout, job of generating suspense. There are times when her direction is playful – the film opens on a black screen and the theatre fills with sinister amplified booming sounds but when the film opens these are revealed to only be the heroine chopping onions on a breadboard – and others that are quite sinister – the moment that Sam Neill places Rachael Blake’s clothes in the fire as she takes a bath. However, the film feels like it needed more scenes like these that either evoke the sinister or play with clichés.

Furthermore, Sam Neill does seem a little miscast. In a role that should be both darkly charming and disturbed, his performance seems far too laidback. At one point, Neill was named ‘The Sexiest Man Alive’, and in films like The Final Conflict (1981) and the magnificent tv mini-series Reilly, Ace of Spies (1983), he was capable of projecting a magnetically sexy charisma. Yet peculiarly he brings none of that to the film, and when the character imprisons Rachael Blake, we never see any of his darkness or mental unbalance. What the role needed was an actor like Gabriel Byrne or Patrick Bergin, both of whom are capable of projecting intensely captivating sexual charisma and revealing a brooding dark side underneath.

While the abduction thriller aspect of the film emerges only routinely, Gaylene Preston then throws a complete dogleg spin on the plot that causes you to immediately sit up and start paying attention. [PLOT SPOILERS]. Here Sam Neill is surprisingly killed off, Rachael Blake returns to the island and as we watch her behaviour becoming increasingly more peculiar as she places Neill’s body in the deep freezer and carries on as though he were still alive. The film becomes even more bizarre as Neill suddenly returns and becomes her lover. It is during this second half that the film starts to become rather good. You have no idea where Gaylene Preston is taking the show and the suspense she generates as Joel Toebeck suddenly turns up on the island, where you are not sure whether he is going to find the dead body or if Rachael Blake is going to kill him, keeps one on the edge of the seat.

Moreover, Preston keeps the scenes where Sam Neill returns to life in a careful state of ambiguity about whether he is real or it is all taking place in Blake’s imagination. It is almost like The Sixth Sense (1999) or The Others (2001) played in reverse – where you know the main surprise that the character is dead from the outset and where the film proceeds onwards playing a subtly ambiguous and misleading game making you think they are alive. It is perhaps The Sixth Sense as filtered through The Innocents (1961), a classic ghost story that hovered in a delicate state of ambiguity as to whether the ghosts we saw were entirely in the governess’s imagination or were real. The final scene the film goes out on, with Rachael Blake dancing with both men at her own wedding, is excellent.

The film was shot in the towns of Greymouth, Wesport and Buller on the rugged West Coast of New Zealand’s South Island. Alun Bollinger, the country’s best cinematographer, does a fine job of shooting the rawness of the coastline. The film makes interesting comparison to Cinema of Unease: A Personal Journey of Sam Neill (1995), the documentary that this film’s star Sam Neill directed, wrote and narrated about New Zealand cinema. In the film, Neill identifies one of the recurrent themes of New Zealand cinema as the sense of a dark and brooding landscape where bad things seem in imminent danger of being about to happen, a thesis that Perfect Strangers could almost have been made to illustrate.

Peculiarly, Perfect Strangers was not the only New Zealand film on the same subject the same year – cinema screens also offered Harold Brodie’s Orphans and Angels (2003), which similarly dealt with a woman who becomes captivated by an at first charming stranger who then reveals his dark side and makes her his prisoner. Both films also maintain a degree of ambiguity about who or what the stranger is.

Trailer here