USA/Australia. 2002.

Crew

Director – Michael Rymer, Screenplay – Scott Abbott & Michael Petroni, Based on the Novel by Anne Rice, Producers – Andrew Mason & Jorge Saralegui, Photography – Ian Baker, Music/Songs – Jonathan Davis & Richard Gibbs, Visual Effects Supervisor – Gregory L. McMurray, Visual Effects – CREO, Gray Matter FX, Manex Visual Pictures, RIOT Pictures & Rising Sun Pictures, Special Effects Supervisor – Brian Cox, Makeup Effects – Bob McCarron, Production Design – Graham ‘Grace’ Walker. Production Company – Material Productions.

Cast

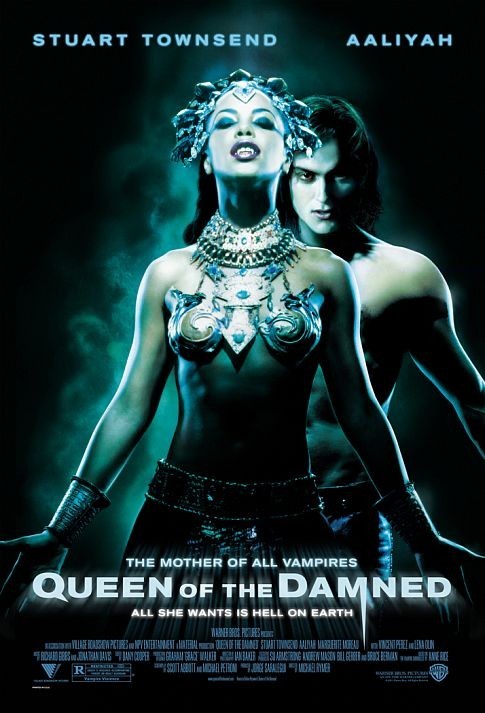

Stuart Townsend (Lestat), Aaliyah (Akashah), Marguerite Moreau (Jessie Reeves), Vincent Perez (Marius), Paul McGann (David Talbot), Lena Olin (Maharet)

Plot

The vampire Lestat rises from the tomb into the present day where he becomes a rock star, making a virtue of his vampirism. This draws the attention of Jessie Reeves, a junior researcher at the Talamascan Center for Paranormal Studies in England, who believes there is truth behind what everyone assumes to be just a pose upon Lestat’s part. She reads Lestat’s 18th Century journal in which he tells how he was turned by the vampire Marius and then came to drink the blood from the preserved statue of the mother vampire Akashah. Obsessed, Jessie goes in search of Lestat who is planning a concert in Death Valley and calling all vampires to come out of their hiding. She finds that the other vampires are planning to kill Lestat for disrupting their anonymity. Lestat’s call has also raised Akashah from the dead and she comes looking for him, wanting him to be her eternal consort.

Anne Rice’s The Vampire Chronicles books, begun with Interview with the Vampire (1976), have developed a cult appeal that has grown to mainstream popularity. Although Rice’s work has increasingly slipped into formula, her vampire stories and other works show no signs of tapering off in appeal. The secret of Rice’s success is less to do with vampires and any of the other horror elements she co-opts as it is to do with a hyper-romanticised homosexual eroticism. This is a facet that runs through all of Rice’s novels and it is no surprise that she writes entire series of S&M erotic novels under two different pseudonyms. The cult for Rice’s vampire novels have always been strongly divided between the gay markets and the slash fandom, the almost entirely female audiences that embrace a concept of erotically feminised masculine relationships.

The first of Rice’s Vampire Chronicles was filmed as Interview with the Vampire: The Vampire Chronicles (1994), which drew vehement protests from Rice herself prior to its release for the casting of Tom Cruise as her favourite bad boy Lestat, something that she then suddenly retracted after seeing the finished film. Queen of the Damned (1988) is the third of Rice’s Vampire Chronicles. (The film series seems to be sidestepping the second novel in the series, The Vampire Lestat (1985), the rights of which are tied up in limbo somewhere still as a potential sequel for Tom Cruise). In 2016, she announed that The Vampire Chronicles was being developed as a tv series.

For all the controversy and dislike that was heaped upon Interview with the Vampire, it still remains the most faithful and literate of the films adapted from Rice’s work. Among the other adaptations of her work, Exit to Eden (1994) turned Rice’s S&M romance into a giggly, self-conscious comedy, while the tv mini-series Feast of All Saints (2001) was no more than a torrid soap opera set among the slaves.Subsequent to this was The Young Messiah (2016) based on the series of books about the life of Christ that Rice wrote following her conversion to Christianity and tv series’ Interview with the Vampire (2022- ) and Mayfair Witches (2023- ). It may well just be that Rice’s often melodramatically overwrought and wordy prose just does not translate well to film. Certainly, the film here emasculates the book. The Talamasca order, which feature prominently in several of Rice’s other series, emerge with thorough ordinariness and the book’s central character of Maharet and her sisterhood make a belated appearance near the end of the film with little impact.

In fact, the film reduces Rice’s languidly romanticised vampires to no more than a feature-length Goth music video. Queen of the Damned has almost no substance beyond Goth posturing. It rarely engages as a plot, all director Mark Rymer seems interested in is Goth poses – Stuart Townsend walking out of a graveyard in slow motion draping a violin in one hand; lying in a pure white marble coffin with his feet up listening to a Walkman; appearing draped across a set of speakers; to the horde of body-pierced, black leather and vinyl clad, ambi-sexual Goth extras that leer in the background with decadent menace. The wall-climbing trick from Dracula (1897) is employed at one point but now it is no more than a party trick being used by Lestat to show off before pouncing on two willing victims. It adds up to a pose that is surface affect and little else.

Furthermore, for all its appeal to a decadent fetishism, the film coyly shuts its eyes whenever it comes to blood and eroticism – it is a surprisingly tame and chaste film for its R-rating. Where the film is at its most successful is the amusing idea of a postmodern vampire who hides his vampirism behind Goth music and the pretence of being a cliche vampire. The opening credits are interestingly placed against one of Lestat’s music videos that recreates the sets of The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1919).

The most pretentious and laughable aspect of all the posturing is Stuart Townsend’s performance as Lestat. Townsend does not so much give a performance as a series of lascivious, cod bad boy poses, prancing through the film with bared chest or open shirts, vinyl pants and a wicked smile. He is like a teenager who most earnestly wants us to notice how wicked and decadent he is play-acting at being. The worst part though is the film’s indecision in regard to the character of Lestat. The first half of the film sets him up as a playful decadent, toying with victims, play-acting at being a vampire, taunting other vampires to come out and play and consumed with a desire to write his ego across the world. Yet the second half gets a case of moral cold feet and backtracks, showing him as nothing more than a clueless little boy who is really innocent at heart, just wants to feel mortal love and lacks the stomach for killing people. Where the first half of the film was all posturing, the second half has reduced its sexy bad boy to a wimp.

Amid the posturing, the one person that does stand out is Aaliyah. Aaliyah attained fame as a hit R&B artist while still only in her mid-teens before making her acting debut in the action film Romeo Must Die (2000) which, despite her bland performance, had her pegged for other acting roles. Her (second) performance here suggests she may well have had some potential as an actress. With blue contacts, exotic accent and weirdly prowling gait, not to mention a mind-boggling array of costume changes, she succeeds in projecting an unearthly exoticism that recalls something of Grace Jones’s performance in Vamp (1986).

There is a certain ghoulishness that hangs over the film. It was originally not even intended as a cinematic release but to go straight to video. However, Aaliyah died in a plane crash in August 2001, aged only twenty-two. In an effort to exploit this, the film was bumped up for a full cinematic release. Certainly, in viewing it, the sets and effects – which include a nifty CGI-styled revisiting of Christopher Lee’s meltdown to dust in Dracula/The Horror of Dracula (1958) – appear to have been lavishly designed for widescreen photography rather than the small screen.

Australian director Michael Rymer next went on within genre material to make the surprisingly good tv mini-series revival of Battlestar Galactica (2003) and to produce/direct various episodes of the subsequent series, as well as to produce/direct on the tv series Hannibal (2013-5) and direct episodes of the mini-series Picnic at Hanging Rock (2018).

Trailer here