Crew

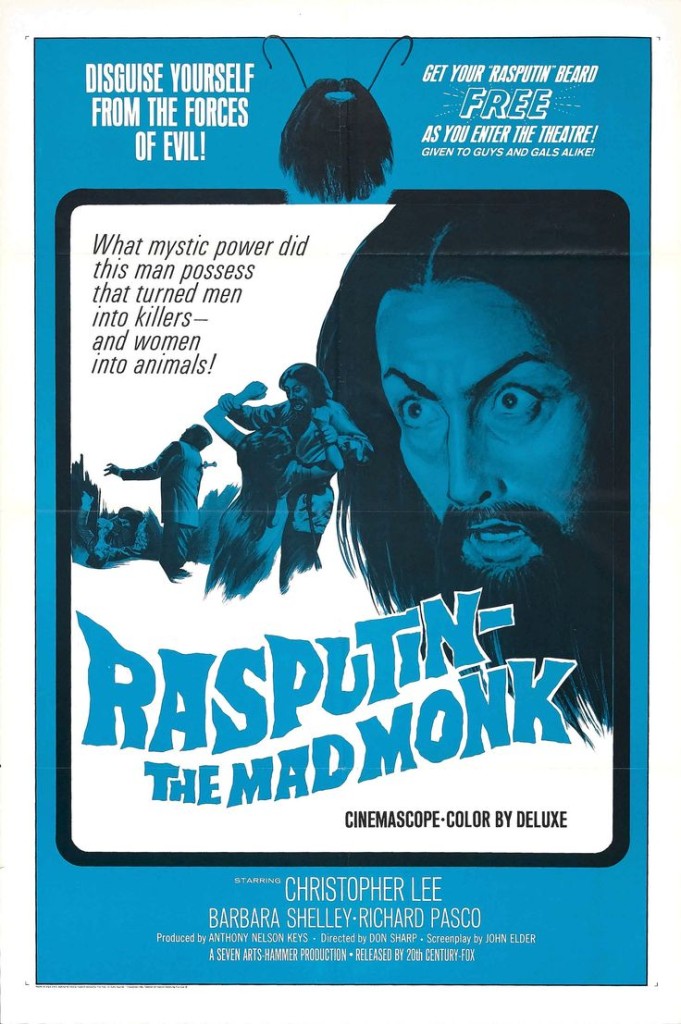

Director – Don Sharp, Screenplay – John Elder [Anthony Hinds], Producer – Anthony Nelson Keys, Photography – Michael Reed, Music – Don Banks, Music Supervisor – Philip Martell, Makeup – Roy Ashton, Production Design – Bernard Robinson. Production Company – Hammer/Seven Arts.

Cast

Christopher Lee (Grigori Rasputin), Richard Pasco (Dr Boris Zargo), Barbara Shelley (Sonia Vasilivitch), Francis Matthews (Ivan Keznikov), Suzan Farmer (Vanessa Keznikov), Dinsdale Landen (Peter Vasilivitch), Renee Asherson (Tsarina Alexandra), Derek Francis (Innkeeper), John Bailey (Dr Zieglov), Michael Cadman (Michael), Fiona Hartford (Tania)

Plot

The wild and filthy monk Grigori Rasputin stumbles into an inn. Upon learning that the innkeeper’s wife is ill with a fever that no doctors can cure, Rasputin heals her with his hands. Immediately after doing so, Rasputin drinks wildly, tries to force his way with the innkeeper’s daughter and severs her fiance’s hand after he tries to intervene, before being forced to flee by an angry mob. When the villagers approach his bishop over this incident, Rasputin is ordered to leave the monastery. He heads to St Petersburg where he falls in with a disbarred doctor. At an inn, Rasputin meets Sonia, a handmaid to the Tsarina. After having his way with Sonia, Rasputin hypnotises her into contriving an accident for the young prince heir Alexei and then recommending him to the Tsarina. He is able to heal Alexei and is acclaimed as a result. Rasputin becomes a confidant of the Tsarina and uses this influence to manipulate the court. However, when he callously discards Sonia and hypnotises her to kill herself, her brother and others plot to kill Rasputin and bring down his diabolic influence over the crown.

In the late 1950s, Hammer Films exploded onto the world stage and created a revolution in horror with their bold, richly colourful revampings of the horror perennials with The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula/The Horror of Dracula (1958). This inaugurated a major British horror industry. Hammer at the forefront and over the next few years remade most of the other Universal horror classics and covered fairly much all the major themes in horror. By the mid-1960s, Hammer were starting to sequelise their Frankenstein and Dracula films, as well as looking around for new horror themes.

While the Hammer name is incontrovertibly intertwined with horror, less well known is their production of historical films. They made a number of these, including swashbucklers and historical adventure films like Dick Turpin – Highwayman (1956), Sword of Sherwood Forest (1960), The Crimson Blade (1963), The Brigand of Kandahar (1965), A Challenge for Robin Hood (1967) and The Viking Queen (1967); as well as various World War II films – The Steel Bayonet (1957), The Camp on Blood Island (1958), Yesterday’s Enemy (1959) and The Secret of Blood Island (1964). They seemed particularly fond of historical films that could be pushed towards horror or at least have an emphasis on the lurid and sadistic, as with the likes of The Stranglers of Bombay (1959) and pirate films like The Terror of the Tongs (1961), Night Creatures (1962), The Pirates of Blood River (1962) and The Devil-Ship Pirates (1964). Rasputin The Mad Monk sits somewhere here, although has clearly been mounted as far more of a horror film than it ever has as an historical film.

Rasputin The Mad Monk focuses on the true life character of Grigori Rasputin. Rasputin is a figure that holds an undeniable fascination in history, as much for the myth that surrounds him – his reputed healing powers, the intensity of his wild man presence (it was claimed that he never bathed), his reputation as an orgiast, his sinister influence over the Russian crown, his almost supernatural-seeming defiance of death – than any historical detail, which often disputes many of these claims. Rasputin’s origin and birthplace is uncertain. He gained a reputation as a holy man and healer of reputedly mystical powers. His fame came in 1905 when Alexandra, the wife of Nicholas II, the Tsar of Russia, came to seek help for their son Alexei who suffered from haemophilia (the inability of blood to clot and cuts to naturally heal). It is unknown how but Rasputin managed to heal Alexei. Both Nicholas and Alexandra soon readily sought Rasputin’s advice, even taking notice of the prophetic visions he made claim to. This gave Rasputin much influence over the court and he began to demand the firing and appointing of officials. Rasputin was also reputed to engage in wild orgies and bedded numerous wives of the aristocracy, although many of these claims may have been made up by rivals who sought to blacken his reputation. This came to a head in 1916 when a group of aristocrats invited Rasputin over and attempted to kill him. Exactly what happened is debated but by a later published account, several attempts were made to kill Rasputin – they feeding him poisoned cakes and wines, then shooting and attempting to club him to death, all of which kept having no effect until he was finally dumped into the nearby river.

Rasputin The Mad Monk was directed by Don Sharp, who had made various Hammer films including Kiss of the Vampire (1962), The Devil-Ship Pirates and their last theatrical film The Thirty-Nine Steps (1979). At the time that he made Rasputin the Mad Monk, Don Sharp had then just come from the success of the lush period version of The Face of Fu Manchu (1965), starring Christopher Lee for Anglo-Amalgamated. Sharp is one of the less celebrated directors in Anglo-horror. Mostly his career was marked by dreary hackwork like The Curse of the Fly (1965), Jules Verne’s Rocket to the Moon (1967) and Secrets of the Phantom Caverns/What Waits Below (1984), although he did make a number of other minor ventures into Anglo-horror with the likes of Witchcraft (1964), the demented Psychomania (1973) and the psycho-thriller Dark Places (1973). When he was given a decent opportunity, as in Kiss of the Vampire and particularly here and The Face of Fu Manchu, which remain his two best films, Sharp showed that he really could do something. In these outings, Sharp brought a touch that made him perhaps the one other director working in this era of English horror to closest approximate the lush floridness that Terence Fisher imprinted on the genre.

Sharp creates an unforgettable opening to the film:– a doctor is seen departing from tending the innkeeper’s wife, shaking his head, whereupon Christopher Lee’s Rasputin barges in through the inn door, looking like a wild man, and then goes up and touches his hands to the wife’s face and heals her, mostly doing so it would seem with the piercing intensity of his eyes. He then returns downstairs, where he gets drunk and dances, before taking the innkeeper’s daughter off to the barn to have his way with her, where her fiance breaks in and tussles with Lee, Lee manages to sever the fiance’s hand with a scythe and immediately returns to force his way with the innkeeper’s daughter, before the angered locals return in a mob, forcing Lee to flee through the barn roof and away on horseback, where we then see him scale a wall to return to his monastery.

The abrupt juxtapositions that these scenes require – between healer and drunken lecher, between wounding a man and returning to force his way onto the man’s fiancee, between the carnality we have just seen and the revelation that the character lives in a monastery – are breathtaking. In the subsequent scene, Christopher Lee is brought before his bishop by the accusing villagers and offers up a superbly arrogant response: “When I go to forgiveness I don’t offer God petty sins, I offer sins worth forgiving.” The scenes in the Cafe Tsigani also have a superb dramatic power – the drinking competition between Rasputin and Richard Pasco’s discredited doctor; Christopher Lee turning on Barbara Shelley after she laughs at his dancing, demanding with piercing intensity: “You will apologise for laughing at me … You will come to me and apologise.” A couple of scenes later we see Christopher Lee on a balcony looking out over the city, seemingly commanding with his eyes that Barbara Shelley hear his call and return to him.

As one can see, this is the Rasputin story mounted as a horror film. Indeed, Hammer’s Rasputin is just another face on the character of the carnal demoniac figure that Christopher Lee incarnated in their Dracula films. Rasputin, like Hammer’s Dracula, is a diabolic force personified, with powers of supernaturally magnetic intensity and representative of a brutish animalism that bursts forth to disrupt polite society. (One of the most interesting dichotomies, one that remains unexplored in the rest of the film, is the contrast between Rasputin who is a holy man with divine healing powers yet is a pure devil figure in his deeds). There are probably few actors better suited to playing the role of Rasputin than Christopher Lee, who was one of the undisputed cornerstones of Hammer’s success. Lee, aside from physically looking the part, has a commanding regal power and a piercing intensity that is not unlike what the historical Rasputin is credited with having.

The latter half of the film is less interesting than Don Sharp’s superb opening. The machinations that go on among the Russian aristocracy are dreadfully standard British upper-class costume drama. Certainly, Sharp makes the murder of Rasputin into a dramatic climax, passing through poisoned chocolates and wine, a syringe stabbed in the neck and Rasputin then thrown out of the window. The scene is well drawn out, although one feels that the film is somewhat pinned in by the adherence to the historical facts – watching Christopher Lee engorge himself on chocolates and wine is not a particularly dramatic climax. (Although even here, the film does depart somewhat from historical fact).

The film is often called historically inaccurate. In fact, this is a case that has been overstated and the film adheres to the Rasputin story more than many might give it credit for. Aside from the aforementioned death scene, there are no outstanding scenes where one can see that the film, at least in terms of what it does depict, blatantly fictionalises the Rasputin story. Certainly, the film regards Rasputin’s powers as actual, but in that nobody has any clear idea of how it was that Rasputin managed to heal Prince Alexei and many did believe that he have such powers, this can be an acceptable dramatic licence. The biggest departure from history is the reasons for the murder of Rasputin. The film contrives a fiction that this was revenge by the brother of a woman that Rasputin hypnotised and then made kill herself after he had finished with her, whereas in fact Rasputin’s assassins were a group of aristocrats who wanted to remove him from influence over the crown.

Rasputin The Mad Monk‘s main problem however is not so much historical inaccuracy as it is historical omission. There is no mention of Alexei’s haemophiliac condition – instead, the film is happy to give the impression that Alexei is a perfectly healthy child that Rasputin sets up with an accident in order to get close to the royal circles. Perhaps as a result of a desire not to cross over into any issues concerning Communism, there is no mention whatsoever made of the Bolsheviks and the Russian Revolution that was occurring around the time, during which Tsar Nicholas was unseated and he and his family murdered. The Tsarina is also made into a fairly minor character – she only gets about two scenes – and we see nothing of Tsar Nicholas II at all.

The film has been beautifully shot on rich sets (and given a superb restoration on the dvd release). The sets, one might note, are also the ones that Hammer used around the same time in Dracula – Prince of Darkness (1965). In particular, the mansion exterior with its iced-over lake where Alexei falls and Rasputin meets his end is the same one where Christopher Lee’s Dracula was finally despatched in Prince of Darkness.

Other screen incarnations of the character of Rasputin include:– the silent German Rasputin The Black Monk (1917), the silent German Rasputin (1928), the Hollywood version Rasputin and the Empress (1932) starring John Barrymore, the German Rasputin, Demon with Women (1932), the French Rasputin (1938), the French Rasputin (1954), the French The Nights of Rasputin (1960) starring Edmund Purdom, the French I Killed Rasputin (1967) wherein one of Rasputin’s assassins Prince Felix Yusupov played himself, the Russian-made Agony: The Life and Death of Rasputin (1981) and Rasputin (tv movie, 1996) starring Alan Rickman. Rasputin has also appeared as a supporting character in the historical film Nicholas and Alexandra (1971) where he was played by Tom Baker, as a black sorcerer in the animated Anastasia (1997) and as the chief villain in Hellboy (2004). There was also the Australian Harlequin (1980), which updated the story of Rasputin to the modern day and had Rasputin played by an appealingly ambiguous Robert Powell. Other oddities include the Boney M disco song Rasputin (1978) and one of the mutants in Marvel’s X-Men series who is named Peter Rasputin aka Colossus.

Trailer here