USA/UK/Luxembourg. 2000.

Crew

Director – E. Elias Merhige, Screenplay – Steven Katz, Producers – Nicolas Cage & Jeff Levine, Photography (colour & b&w) – Lew Bogue, Music – Dan Jones, Digital Effects/Titles – Cine Image, Special Effects Supervisor – Rick Weissenhaan, Makeup – Pauline Fowler & Julian Meriya, Production Design – Assheton Gordon. Production Company – Saturn Films/Long Shot Films/BBC Films/Deluxe Productions/Shadow of the Vampire Ltd.

Cast

John Malkovich (Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau), Willem Dafoe (Max Schreck), Cary Elwes (Fritz Arno Wagner), Udo Kier (Albin Grau), Catherine McCormack (Greta Schroeder), Robert Aden Gillett (Henrik Galeen), Eddie Izzard (Gustav von Waggenheim), Ronan Vibert (Wolfgang Muller)

Plot

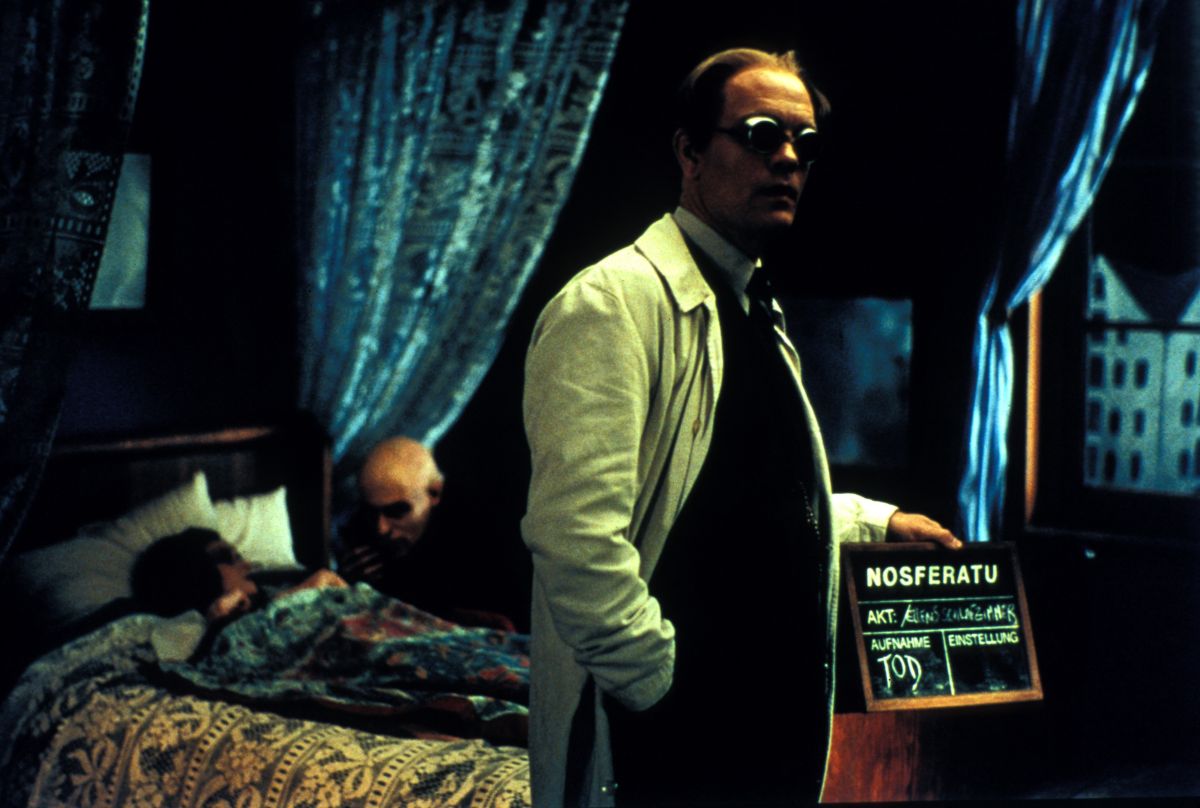

In 1921, the brilliant, highly acclaimed German film director Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau seeks to make the greatest and most realistic vampire film of all time. He calls his film ‘Nosferatu’ after Bram Stoker’s widow refuses him permission to film ‘Dracula’. He takes his crew to the small town of Wismar. In the role of the vampire, Murnau employs an actor called Max Schreck who is so much of a character actor that he even appears in his own makeup. The unnerved crew soon discover that Schreck is a real vampire and that Murnau has promised him leading lady Greta Schroeder to feed upon at the end of shooting.

Shadow of the Vampire was announced immediately after the critical success of Gods and Monsters (1998), which was based on the life of the real-life genre director James Whale. Indeed, the initial pitch for Shadow of the Vampire had it sounding like it was a similar biopic of silent German director F.W. Murnau. Gods and Monsters was an honest attempt to speculate about true events surrounding Whale’s death. On the other hand, Shadow of the Vampire takes reality as a springboard for a What If story – in this case, what if F.W. Murnau shot Nosferatu (1922) using a real vampire?

The important difference between the two is to realize that Shadow of the Vampire is a work of fiction, not of historical accuracy, even though it mimics such. Max Schreck, although the character has attained a certain creepy mythology, was a real flesh and blood actor and did not die in 1921 as is stated here but went on to make some twenty other films over the next decade up until his death in Munich in 1936 of a much more mundane heart-attack.

Nor were screenwriter Henrik Galeen and cinematographer Fritz Arno Wagner killed as depicted in the film – Henrik Galeen went onto write other fantastic classics such as Waxworks (1924), became a director with the remakes of The Student of Prague (1926) and Alraune (1928) and died in 1949 after emigrating to the US to flee the Nazis, while Fritz Arno Wagner filmed more than 100 films including such Fritz Lang classics as Spies (1928), M (1931), The Testament of Dr Mabuse (1933) and did not die until 1958.

There are a few other inaccuracies – the film makes the claim that F.W. Murnau wanted to make the “most realistic vampire film of all time” – but as there had been no other vampire films made before Nosferatu, it seems difficult to make such a qualitative statement. Shadow of the Vampire also calls F.W. Murnau the greatest filmmaker of the German silent era (which is probably true) but most of Murnau’s reputation came as a result of Nosferatu and with later films such as The Last Laugh (1924), Faust (1926) and particularly Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927). The film’s characterisation of Murnau as a reckless tyrant obsessed with his art to the extent he is prepared to sacrifice human life also verges on the libellous. However, as long as one can get the proper perspective, one can enjoy Shadow of the Vampire for exactly what it is – a work of historical fiction, not of accuracy.

As such, Shadow of the Vampire is rather enjoyable. The sense of verisimilitude achieved is strikingly well done. Most impressive is the haunting and beautiful credits sequence all in a stylised three-dimensional recreation of 1920s art deco frescoes. Director E. Elias Merhige’s recreations of the camera set-ups of the original Nosferatu are striking in their exacting precision. There is almost a sense of watching the original Nosferatu and being able to stop the film you have just seen and walk around the edges of the frame to watch the filmmakers at work.

Merhige is only too aware of the effect of this and starts to play into and against audience expectations – when it comes to the scene where Orlock picks up the locket with the photo of Johannes’s wife and Willem Dafoe playing Orlock picks it up and looks at the photo of Greta Schroeder who has been promised to him by Murnau, the expected line “What a beautiful throat” rather wittily comes out as “What a beautiful bosom.” The classic death scene with Ellen luring Orlock to her bed and keeping him until dawn is revealed in reality as being conducted by an actress who is too drug-addled to be able to wield the stake through the heart that was originally intended to be Orlock’s form of dispatch, while the film’s wonderfully cinematic death scene where Orlock is killed by the dawn’s rays is revealed as being Schreck’s death caused by the accidental opening of the set doors.

Steven Katz’s script pays exceptional attention to characters and E. Elias Merhige has an excellent cast on hand. Even the smaller parts in the film are filled with excellent, wonderfully nuanced characterisations – especially notable being Cary Elwes’s fine performance as the handsome, gung ho cameraman. Of course, the performance that had everyone talking and received a number of award nominations (the Golden Globes and the LA Film Critics Awards) is Willem Dafoe’s Max Schreck. It is a part where Willem Dafoe completely submerges himself in the role and is totally unrecognisble on screen. His performance has a creepy fascination, although is one that is very different to Max Schreck’s.

This is a vampire cast as a pathetic and aged figure that has lost all former glory and lacks anything in the way of classic vampire movie magnetism, evil or dark sexuality. It is a performance considerably abetted by the extraordinary character soliloquies that Steven Katz provides – most haunting of all being the one where he tells how the saddest part of Dracula (1897) is the scene where we see Dracula forced to act as his own servant, a scene where we see the touching sense of an aristocrat (not Dracula, but Schreck) having been reduced to squalor.

Director E. Elias Merhige had previously made the extremely weird art film Begotten (1990) concerning a day in the life of God, who disembowels himself, and Mother Earth. Subsequently, Merhige went onto make the serial killer thriller Suspect Zero (2004). Screenwriter Steven Katz went onto write the ghost story Wind Chill (2007) and write/produce the Steven Soderbergh tv series The Knick (2014-5).

(Winner in this site’s Top 10 Films of 2000 list. Winner Best Original Screenplay and Nominee for Best Supporting Actor (Willem Dafoe), Best Musical Score and Best Makeup Effects at this site’s Best of 2000 Awards).

Trailer here