USA. 1987.

Crew

Director – Joseph Ruben, Screenplay – Donald E. Westlake, Story – Donald E. Westlake, Brian Garfield & Carolyn Lefcourt, Producer – Jay Benson, Photography – John Lindley, Music – Patrick Moraz, Special Effects – Bill Orr, Production Design – James William Newport. Production Company – ITC Productions.

Cast

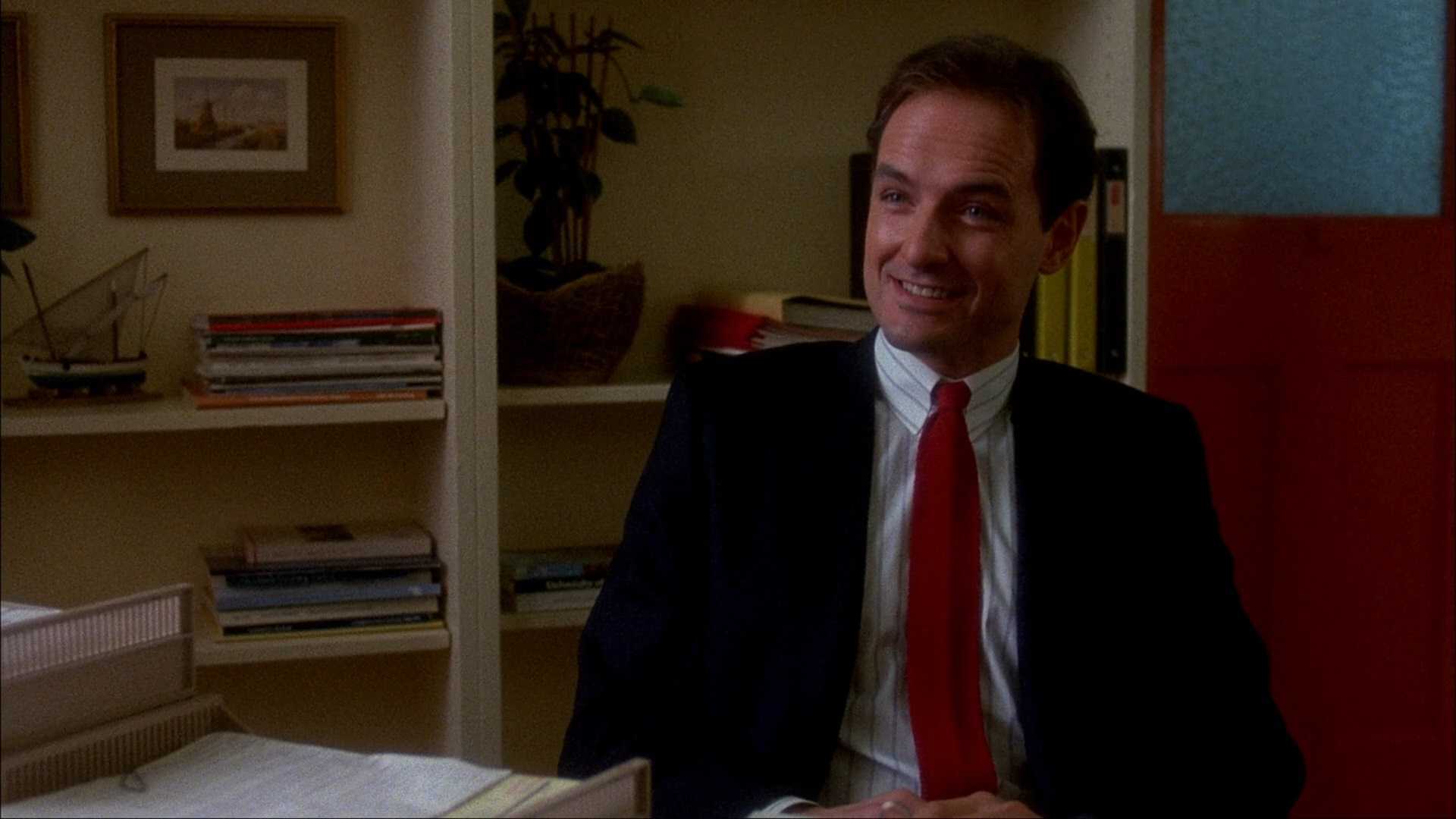

Terry O’Quinn (Henry Morrison/Jerry Blake/Bill Hodgkins), Jill Schoelen (Stephanie Maine), Shelley Hack (Susan Blake), Stephen Shellen (Jim Ogilvie), Charles Lanyer (Dr Bondurant)

Plot

Henry Morrison desires the perfect family – to such extent that he searches for divorcees or widows with established families and marries them. However, when the family does not meet up to his expectations, he massacres them and moves on to set up identity in another town and find another family. After slaughtering his previous family, he sets up as real estate salesman Jerry Blake and marries widow Susan Maine. His image of the perfect family comes under threat when Susan’s teenage daughter Stephanie, who has developed a dislike of Jerry, begins to suspect that he may be a wanted killer.

In a decade (the 1980s) when the psycho-thriller had become supplanted by the slasher film and streamlined to the point that the films were little more than novelty killing machines, The Stepfather proved to be a breath of intelligence amid the dross. It was perhaps the most scintillating of the new breed of psycho films to emerge during this time and one of the finest psycho-thrillers to emerge since indeed Alfred Hitchcock turned showering into a blood sport.

In almost all slasher films and psycho-thrillers, from Psycho (1960) through Halloween (1978) and Friday the 13th (1980) on, there is a deep-seated conservatism, a reinforcing of puritan ethics – that the sexually impure will be punished, that those who fail to take life seriously, those who indulge in dope and alcohol will be punished for their sins. The Stepfather is hardly different – the point where Terry O’Quinn loses it for good with his adopted family of Shelley Hack and Jill Schoelen is the moment he finds Schoelen kissing her boyfriend goodnight on the front porch. The ingenuity of The Stepfather is that it consciously carps at (rather than reinforces) the very puritan values that most American psycho-thrillers embody. This is a film that seems to have been conceived as Father Knows Best (1954-60) with Norman Bates playing the father.

You could maybe draw parallels between The Stepfather and another film that came out the same year – Fatal Attraction (1987). Both films are psycho-thrillers. Both centre around concerns with Family Values, a buzzword that emerged in the 1980s, coined by conservative American political campaigners. Both are also films at mirror opposites of one another. Fatal Attraction concerns itself with a family man (Michael Douglas) who makes a bad decision (to have a fling) and pays for his mistake. The warmly presented status quo of his family and forgiving wife is restored when he eliminates the psychopathic, feminist-sympathizing single woman who seemed determined to wreak her revenge by tearing his home life apart.

By contrast, The Stepfather casts the man of the household defending these Family Values as the psychopath. Fatal Attraction is concerned with preserving Family Values – there is no questioning of the wholesomeness of Michael Douglas’s life with his wife and daughter; where as on the other hand, The Stepfather is intent upon showing these values to be cloying, outmoded and makes the clear point that the ludicrously clean-living ideals of family as promulgated by 1950s tv shows are out of step in the 1980s.

The contrast between both films can be seen even more so in the way the two were made – where Fatal Attraction was a big-budget studio film, The Stepfather was an independent, modestly-budgeted production; and where Fatal Attraction was a colossal box-office success but polarized public opinion, The Stepfather found only modest success but great critical acclaim.

There is some fine direction from Joseph Ruben. The opening, which cuts across a quintessential suburban avenue into a bathroom where Terry O’Quinn changes into a three-piece suit and walks out through a living room filled with the butchered remains of his family, calmly picking up children’s toys on his way out, is one of the most ingeniously nonchalant and disturbing set-ups in any horror film. Mostly, this is a film where the suspense is carried by the uncommonly tight plotting (apart from a crack Bondurant makes about charging his schizophrenic patient double that no self-respecting psychologist would make).

The script comes from thriller writer Donald E. Westlake, whose books have been adapted into films like Point Blank (1967), The Grifters (1990) and The Ax (2005). Westlake mounts some gripping twists – there is that oh so delicious moment where psychologist Charles Lanyer, pretending to be a client of O’Quinn’s, accidentally traps himself with a slip of the tongue, or the chilling moment where Terry O’Quinn starts to lose touch and slip into the new role he is creating during a phone-call.

A great deal of the film’s believability comes from the performance by Terry O’Quinn. It is an extraordinary performance that O’Quinn gives, where he can go from playing a man of instant warmth with a patient and utter belief in the banalities of Leave It to Beaver (1957-60) Americana to a sudden cold glint of eyes and chilling clench of jaw. A sense of sympathy is even created for O’Quinn – there is a lovely shot when he turns from his family crumbling around him to longingly stare at the perfect family group across the street from him and one is given a disturbingly plausible touch of insight into his corner of the American Dream.

The film digs away with an at times unnervingly incongruous sense of black humour – “My father’ll kill me,” is Jill Schoelen’s prophetic first thought upon news of her expulsion from school; or Terry O’Quinn’s return from murdering Schoelen’s therapist: “Sweetheart, I have some bad news about Dr Bondurant,” followed by a pregnant wait, “He’s not going to be able to make his appointment.” The only point the film falters is at the climax, which is routine in terms of the genre, where Joseph Ruben seems to see the need to take it into traditional slasher territory – Jill Schoelen taking a gratuitous shower and with Terry O’Quinn wielding a knife and predictably getting up again after being stabbed.

There were two sequels, Stepfather II (1989), which featured a return performance from Terry O’Quinn, and the terrible Stepfather III (1992), where O’Quinn was replaced by Robert Wightman and the difference explained away by plastic surgery. Neither film emerges with the conceptual ingenuity that this does and both are routine slasher films. As part of the fad for 70s/80s remakes, there was a remake of the original with the dull The Stepfather (2009) where Terry O’Quinn was replaced by Dylan Walsh.

Director Joseph Ruben had previously made the sf film Dreamscape (1984) about psychics warring inside people’s dreams. For a brief time after The Stepfather, Ruben seemed to go onto a career in psycho-thrillers with Sleeping With the Enemy (1991), which had Julia Roberts as a wife pursued by a psycho husband, and The Good Son (1993) with Macaulay Culkin as a psychopathic child. Ruben has since gone onto much blander fare with the action film Money Train (1995), the Malaysian jail imprisonment horror Return to Paradise (1998), the thriller Penthouse North (2013) and the historical drama The Ottoman Lieutenant (2017), although did return to the genre with the interesting alien abduction film The Forgotten (2004).

Trailer here