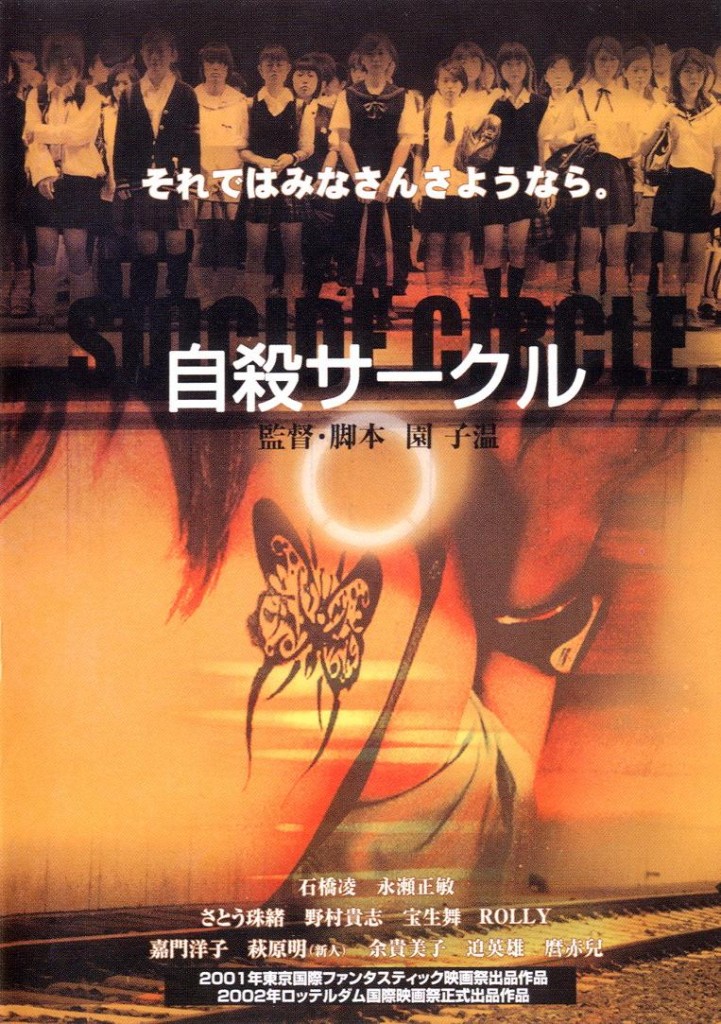

aka Suicide Circle

(Jisatsu Circle)

Japan. 2002.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Shion Sono, Photography – Kazuto Sato. Production Company – Omega Project Inc

Cast

Ryo Ishibashi (Detective Kuroda), Masatoshi Nagase (Detective Shibu), Akaji Maro (Detective Murata), Rolly (Genesis), Takashi Nomuri (Jiro), Mai Hosho (Akko Sawada), Tamo Sato (Yoko Kawaguchi)

Plot

54 schoolgirls link hands and jump in front of the train at Shinjuku Station. As other copycat suicides sprout up and high schools form Suicide Clubs, police begin to treat the rash of deaths as suspicious. At each scene, the police find a bag containing a roll stitched together from squares of skin taken from the victims that will be at the next mass suicide. At the same time, a mystery hacker directs the police to a website that is counting the number of victims killed before they die.

Several Japanese films in the 00s have taken up the theme of wayward youth – see the likes of Battle Royale (2000), Blue Spring (2001) and the Crows films. As a result, you might begin to suspect that Japanese teens have lost control and are heading on a one-way ticket to the edge of the cliff. Suicide Club was one film to jump on this bandwagon – it has some alarming real world parallels with such suicide clubs among disaffected teens becoming a social problem in Japan. (Indeed, this particular web page gets an alarming number of hits from search engines under phrases like ‘suicide clubs’ and ‘japanese suicide clubs’). Although, rather than any sociological portrait of wayward Japanese youth, Suicide Club is more centred in the Japanese horror wave that began with Ring (1998).

Suicide Club starts promisingly. There is an attention-grabbing opening where 54 schoolgirls line up on a railway platform, join hands and jump in front of the train, splattering the train and platform with a tide of blood. Director Shion Sono gets down the entertainingly schlocky mix that made Ring so much fun. The film is filled with scenes that sit between schlock horror and dark humour – giggly pupils gathering on the roof of a building, spontaneously deciding to form a suicide club and jumping to their deaths; the spookiness at the hospital and the surreal image of the bloodied bag sliding into view; the revelation of the glitter rock villain who karaokes songs while stomping on what look like hamsters writhing in bags.

These scenes are tempered by a intriguing building mystery – the mysterious website counting the deaths of the victims in advance, the enigmatic teenage girl hacker The Bat tipping the police off, and the wonderfully grisly image of strips of skin each taken from different victims and sewn into a ribbon and left at the previous crime scene. Even if the balance between serial killer thriller and black comedy schlock sits uneasily, Suicide Club creates a compulsively mystery as to what on Earth is going.

… Only for Shion Sono to promptly lose it altogether. It soon rapidly becomes apparent that as screenwriter Shion Sono has as little idea as to what is going on as the entirely baffled audience does. There is an explanation of sorts towards the end where we are shown victims at the concert being lined up and having the strip of skin cut off with a plane saw and see that the suicides are being programmed via subliminal messages inside cellphones and pop videos. However, there is zero explanation of the agency behind the suicides, unless one can believe the ever-so-slightly improbable notion that they it is being stage-managed by a pre-adolescent pop band. There is also no explanation of how the suicides are chosen, who masters the website, and most of all why, except for the kid band mouthing something unclear about the heroine about losing her connection to herself.

The sort-of explanation comes close to Claude Chabrol’s Dr M/Club Extinction (1990), which was about a mastermind programming people to mass suicide using subliminals inside mass media. There is maybe something also something of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s deeply unfathomable Cure (1997) about a mystery man hypnotizing people into becoming killers, as well as Kurosawa’s Pulse (2001) about mass suicides.

In comparison to Kurosawa, Suicide Club seems acutely confused, with Shion Sono’s seeming need to go off on a tangent with a new idea every five minutes making the film seem amateurish and muddled. Even as a police procedural it is unbelievable – it is only some three-quarters into the film before the police actually come up with the idea of tracking down the IP address of the website, which is something so obvious that you wonder why it was not the first thing on their list.

Shion Sono made a sequel with Noriko’s Dinner Table (2005). Over the next few years, Sono has made a number of other genre filns, including the perversely disturbed Strange Circus (2005); Exte: Hair Extensions (2007) about killer hair extensions; Cold Fish (2010) about serial killings, tropical fish salesman and the reclamation of male pride; Guilty of Romance (2011) about sexual fulfilment and murder; Himizu (2011) about murderous children; The Land of Hope (2012) set in an alternate world; Tokyo Tribe (2014), a near-future set film about gangland wars where much of the dialogue is delivered in rap; Love and Peace (2015), an awkward romance involving talking animals; the reality blurring Tag (2015); the comedy The Virgin Psychics (2015); The Whispering Star (2015) about an intergalactic delivery android; Tokyo Vampire Hotel (2017), The Forest of Love (2019) and the post-apocalyptic English language Prisoners of the Ghostland (2021).

Trailer here