Crew

Director – Martin Scorsese, Screenplay – Paul Schrader, Producers – Julia Phillips & Michael Phillips, Photography – Michael Chapman, Music – Bernard Herrmann, Special Effects – Tony Pamalee, Makeup Effects – Dick Smith, Art Direction – Charles Rosen. Production Company – Columbia.

Cast

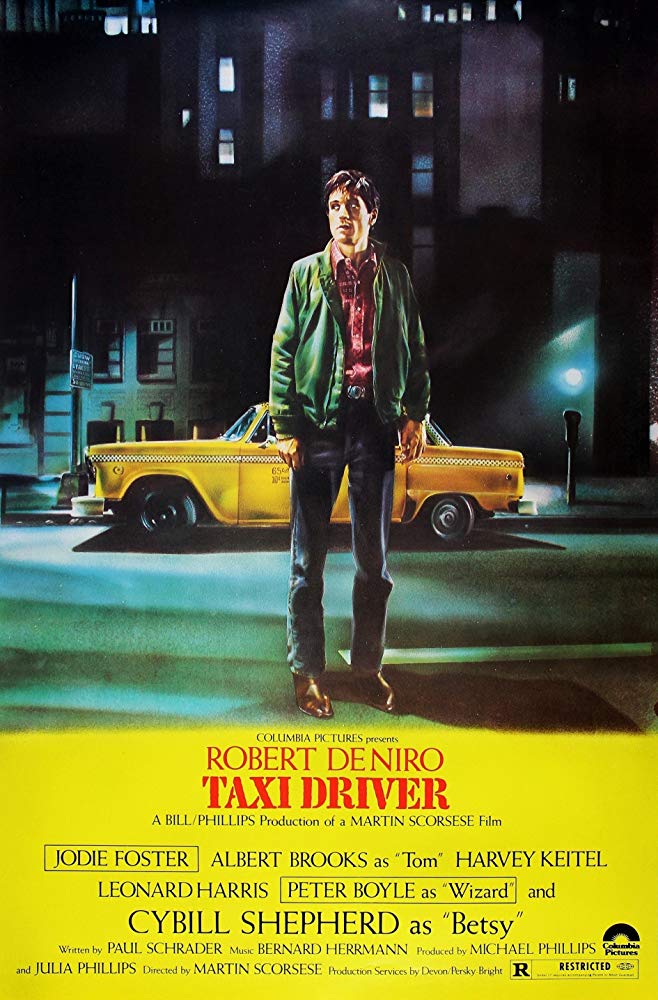

Robert De Niro (Travis Bickle), Cybill Shepherd (Betsy), Jodie Foster (Iris Steenman), Peter Boyle (The Wizard), Harvey Keitel (Matthew), Albert Brooks (Tom)

Plot

Vietnam veteran Travis Bickle takes a job as a taxi driver, driving long hours to curb the boredom of his insomnia. As he drives, Bickle becomes disgusted with the sickness and corruption he sees around him on the streets of New York City. He befriends Betsy, a girl working at a Senator’s campaign office, and asks her out. However, after Bickle tries to take her to a porn movie, Betsy refuses to see him anymore. Bickle buys up an arsenal of guns and starts practicing with them. He hangs about the Senator’s campaign rallies with weapons hidden upon his person. He then becomes fixated with the 12-year old prostitute Iris, wanting to deliver her back to the family life he believes she should be leading.

To my mind, Martin Scorsese is maybe the greatest of all modern American directors. While other directors may surpass Scorses in terms of style or making big, bold underlined statement films, nobody makes films with the passion and intensity that Martin Scorsese does. What is so striking about Scorsese’s curriculum vitae is his versatility as a director. His work has covered everything from reality-based gangster films – Goodfellas (1990), Casino (1995) and The Departed (2006), to psycho-thrillers – Cape Fear (1991) and Shutter Island (2010), musicals – New York, New York (1977), the woman’s film – Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974), the rock documentary – The Last Waltz (1977), No Direction Home: Bob Dylan (2005) and Shine a Light (2008), to Merchant Ivory-type period drama – The Age of Innocence (1993) and black comedy – The King of Comedy (1982) and After Hours (1985). Scorsese goes out on a limb and makes passionate films about religion (he himself once wanted to enter Catholic seminary) such as the highly controversial The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), Kundun (1997) about the Dalai Lama and Silence (2016) about the Jesuits in Japan. He makes films about urban grimness – Mean Streets (1973), Bringing Out the Dead (1999) and Taxi Driver. These are films that eschew the thriller structures that a crime drama might take and feel like naked and open sores, bleeding with a dark, disturbed venal ichor. In all of Martin Scorsese’s genre hopping, none of his films make concessions towards easy commercialism and all bear a distinctiveness that makes them a Martin Scorsese film.

Taxi Driver is to my thinking Martin Scorsese’s best film. When it came out, Taxi Driver was nominated for a Best Picture Oscar by the usually ultra-conservative Academy of Motion Pictures and conclusively put Robert De Niro on the map as a name. Taxi Driver is rarely a film that is reviewed by historians of the horror genre as a psycho film – possibly because of the fascinatingly ambiguous moral messages it sends out – but it is an urban psycho film that is as startling in its own way as Psycho (1960) and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) were in their time.

Taxi Driver is certainly a unique psycho film – one where the psycho is the nominal hero and the antagonist of the piece almost seems to be New York City itself. Scorsese and photographer Michael Chapman imbue New York City with a seething, unsettled pent-up energy. The intensity of Taxi Driver can unnerve one – a relentless, restless anger throbs beneath the surface, sexuality and violence glitter and seem to merge into one and the same with disturbing ease. As in Scorsese and screenwriter Paul Schrader’s very similar Bringing Out the Dead (1999), the narrator is an alienated passive observer whose profession involves driving through the chaos, indifferently, detachedly observing the moral decay of the society around him. We hear Robert De Niro’s haunted voice coming across the soundtrack: “All the animals come out at night – whores, scum, pussy, buggars, queens, fairies, dopers, junkies, sick, venal. Some day a real rain’ll come and wash all this scum off the streets.” Over the top of it, Bernard Herrmann creates a grinding intensive score, contrasted with beautifully mellow sax solos.

With Taxi Driver, Robert De Niro was transformed into a James Dean for the 1970s. As Dean became the voice of 1950s dissatisfaction, so Robert De Niro came to embody a restless urban alienation, a sense of trying to find moral certainty in a world that no longer makes sense, and of troubled post-Vietnam violence pent-up and ready to explode. There is something genuinely disturbing as we follow De Niro through this moral Hell.

One of the most chilling moments is a cameo from Scorsese himself as a cab customer who calmly describes to De Niro in graphic detail how he is going into an apartment where his wife and lover are to shoot the both of them. There is a disturbing matter-of-factness to the sequence where Robert De Niro buys the guns as he and the salesman stand nonchalantly discussing the purchase with the arsenal laid out across a hotel bed, and then of De Niro practicing pulling his guns in front of a mirror – his famous “You talkin’ to me?” line – and building fast-loading rigs to go up his sleeve. Through the first hour of this, Scorsese builds the film towards a looming sense of something about to detonate. When Taxi Driver does explode into a bloodbath, it does with a grim brutality.

This is far beyond anything ever attempted in Psycho or Texas Chain Saw – there Norman Bates and Leatherface were psychos that had been set up as antagonists. Up against them we had average, ordinary whitebread protagonists – we could look to Janet Leigh, Vera Miles and Marilyn Burns and we could ascertain the insanity of Norman Bates and the cannibal family by the threat they presented to the very ordinariness of such heroines. That ordinariness gave their psychosis a distancing effect, we at least had the comfort that it was Other to our protagonists whom we identified with. However, in Taxi Driver the protagonist is the madman, or at least begins as an ordinary person and gradually makes a descent into being the psychopath. Martin Scorsese offers the audience the choice either to be dragged into Travis Bickle’s decaying insanity or to leave the theatre. Our participation in Taxi Driver is no other choice but to go along with the never stated reasons for Robert De Niro’s looming violence.

Martin Scorsese views his native New York City on two levels – the dark, festering underbelly where the ugliness of human need is laid open and a pristine middle-class layer that seems almost distantly above and far beyond the reaches of any character who lives in this world. Part of Travis Bickle’s psychosis seems to come in trying to place the moral framework of one world onto the other. Cybill Shepherd is held up as an almost impossibly distant figure of desirability and normalcy belonging to this other world – her rejection of Robert De Niro seems to come out of his inability to understand what is norm in his world (attending porn cinemas) is improper in hers. There is a muted sense of black humour to be found in the ridiculous platitudes of the senator’s campaign promises to clear up crime contrasted to the overwhelmingly pervasiveness of the moral rot that we see all around us; and of Robert De Niro’s attempts to make Jodie Foster conform to a traditional child role, something immediately punctured by her sharp, streetwise practicality (a fine performance of tarnished innocence from the twelve year-old Foster).

Even the seemingly triumphal note that Taxi Driver ends on – Bickle called a hero for saving Iris – is an ambiguous settlement. It is the same place a more standard action film might end and is one that seemingly vilifies Bickle’s actions. However, being placed in the position of a traditional movie happy ending end makes us feel uneasy – having followed Robert De Niro on his descent into insanity, being also asked to applaud it too is disturbing. You are not entirely sure if this ending is a place where Scorsese and Paul Schrader regard as Bickle having gained his redemption or else a place where heroic triumph and the restoration of a family values status quo is to be regarded as ironic in light of the overwhelming intensity of the sleazy world that Taxi Driver has delved into.

You might compare Taxi Driver with the Tim Burton Batman (1989) where Michael Keaton’s incarnation of the comic-book character was a similar dark disturbed avenger prowling a morally diseased city – Taxi Driver is in some ways Batman without capes and masks, a realist Batman. Yet Batman never pushed the material as far as Scorsese and Paul Schrader do, Batman is ultimately a vilified hero where we regard his actions as right, with Taxi Driver you emerge worryingly puzzled about the nature of individual heroism.

Taxi Driver also taps into the mood of the era – both the sense of social unrest that loomed without ever emerging into the open following the end of the Vietnam War and the number of political assassinations that rocked the country during the 1960s. What is also disturbing about Taxi Driver is that Travis Bickle’s tentative attempts at political assassination have no clear purpose in targeting the Senator, other than the vague connection of Bickle’s being rejected by a woman who works for the campaign. (Taxi Driver was given a disturbing real-life resonance in 1981 when John Hinckley Jr developed a stalker fixation with actress Jodie Foster and attempted to shoot then-President Ronald Reagan in imitation of Bickle). Although, in truth, much of the film feels like a snapshot of the mind of screenwriter Paul Schrader who was hanging out in L.A., trying to get a break into the industry, feeling powerless (before being switched onto guns by director John Milius and thereafter sleeping with a gun by his bedside), having fantasies of shooting up people at political conventions and wanting to bed desirable women but feeling inadequate.

Martin Scorsese’s other ventures into genre material include the remake of Cape Fear (1991); Bringing Out the Dead (1999), a quasi-ghost story about a haunted ambulance driver that returns to Taxi Driver territory; the reality-bending psycho-thriller Shutter Island (2010); and the children’s film Hugo (2011) about silent film pioneer Georges Melies. Scorsese also makes occasional acting appearances and has been in several genre films – as Vincent Van Gogh in Akira Kurosawa’s fantasy anthology Dreams (1990), as himself in Albert Brooks’s Hollywood satire The Muse (1999) and as a talking fish in the animated Shark Tale (2004). He also produced the modernised tv mini-series Frankenstein (2004), the documentary Val Lewton: The Man in the Shadows (2007) about the 1940s horror producer, the Norwegian-set serial killer thriller The Snowman (2017), Shirley (2020), a biopic of horror writer Shirley Jackson, the ghost story The Eternal Daughter (2022), and narrated/produced the documentary Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger (2024).

Screenwriter Paul Schrader, a frequent collaborator of Martin Scorsese’s, has racked up a number of genre credits as director with the likes of the remake of Cat People (1982), the psycho-sexual thriller The Comfort of Strangers (1990), the tv movie Witch Hunt (1994) set in an alternate world Hollywood where magic is real, the faith healing film Touch (1997) and Dominion: Prequel to The Exorcist (2005), as well as scripts for Brian De Palma’s reincarnation thriller Obsession (1976) and Scorsese’s Bringing Out the Dead.

Trailer here