USA. 1974.

Crew

Director/Producer/Additional Photography – Tobe Hooper, Screenplay – Tobe Hooper & Kim Henkel, Photography – Daniel Pearl, Music – Tobe Hooper & Wayne Bell, Makeup – W.E. Barnes & Dorothy Pearl, Art Direction – Robert A. Burns. Production Company – Vortex.

Cast

Marilyn Burns (Sally Hardesty), Paul A. Partain (Franklin Hardesty), Edwin Neal (Hitch-Hiker), Jim Siedow (Cook), Gunnar Hansen (Leatherface), Allen Danziger (Jerry), Teri McGinn (Pam), William Vail (Kirk), John Dugan (Grandfather)

Plot

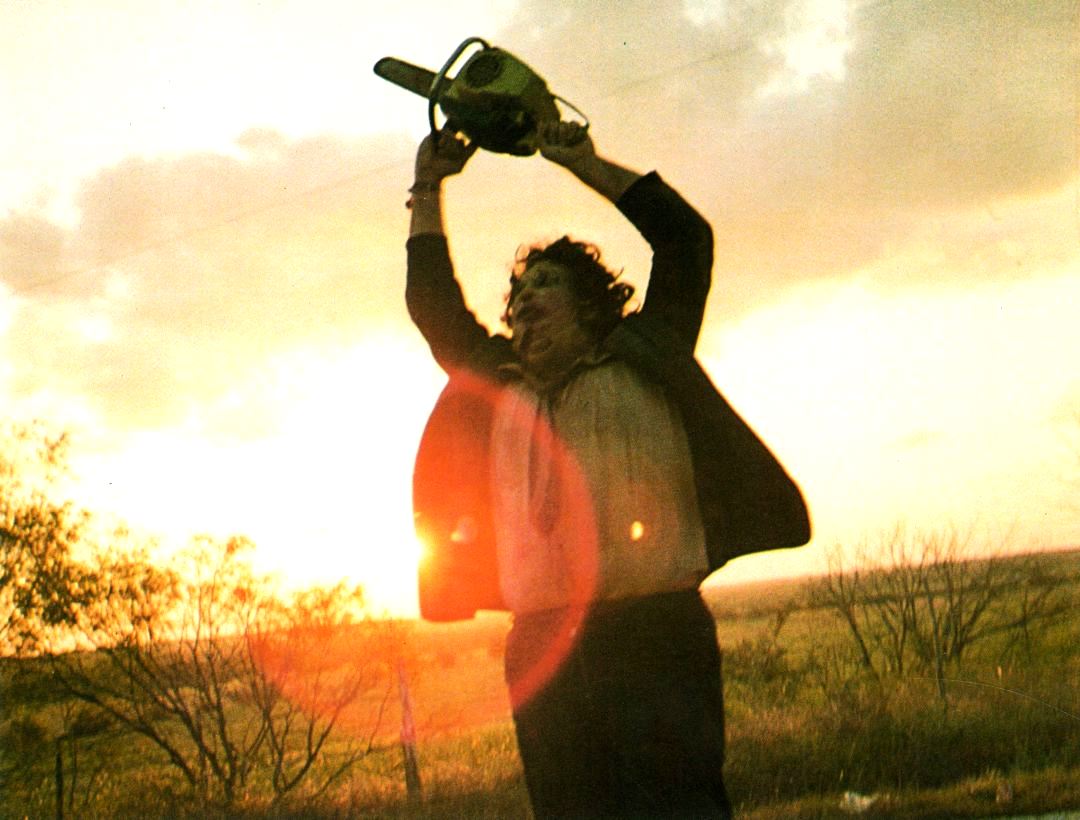

Sally Hardesty and her paraplegic brother Franklin, along with Sally’s boyfriend and another couple, Kirk and Pam, travel across Texas to visit their childhood home. They pick up a hitchhiker who proves crazed and tries to set fire to the van and slashes his own and Franklin’s wrists before jumping out. They continue on to the homestead. Kirk and Pam go searching for a waterhole and inadvertently cross onto another property where a huge man in a leather mask smashes Kirk over the head with a hammer and then impales Pam on a meathook to watch while he cuts Kirk’s body up with a chainsaw. The others receive a similar fate from the leather-faced man and his bizarre family, culminating in the prolonged torture and pursuit of Sally.

Former schoolteacher Tobe Hooper claims to have gotten the idea for The Texas Chain Saw Massacre while Christmas shopping. He was accidentally pushed against a rack of chainsaws by crowds in a hardware store and had a flash fantasy where he wished he could use one of the chainsaws to demolish the crowd. He says at that moment the film “opened up before his eyes”. So began one of cinema’s most famous attempt to push back the limits of the permissible. It was not the first – Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left (1972) was there a couple of years earlier and went even further than The Texas Chain Saw Massacre ever did in its brutality and savagery themes – but The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was the most notorious.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and The Last House on the Left were part of a genre of independent horror films in the 1970s that went out on a limb and were determined to shock. The seminal work here was Night of the Living Dead (1968) with its image of the dead come back to life to devour the living, which came with a rawness that broke down all doors in terms of expectation in a horror film. In more mainstream fare, there was Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971) about a mild-mannered mathematician who is driven to brutal acts of survivalism during an assault on his home by unruly locals, and not long after that John Boorman’s Deliverance (1972) about four men whose wilderness idyll is brutally overturned as they are tortured and raped by a group of backwoods hillbillies.

Straw Dogs, Deliverance and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre formed the basics of what one has termed the Backwoods Brutality cycle. This mini-genre of Backwoods Brutality films circle around the theme of ordinary people forced to defend themselves by an assault that comes out of the blue without rhyme or reason; the sense of a home or a placid middle-class way of life at siege from forces of lawlessness beyond the door; and the impression of there being a clear dividing line between civilized America in the cities and the backwoods where people have become inbred, brutish and harbour a deep-seated resentment of interlopers.

These themes were echoes in many other films of the era and since including The Last House on the Left, Death Weekend/The House by the Lake (1976), Fight For Your Life (1977), Wes Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes (1977), The Evictors (1979), Day of the Woman/I Spit on Your Grave (1978), Mother’s Day (1980), Savage Weekend (1981), Just Before Dawn (1981), Southern Comfort (1981), Bridge to Nowhere (1986), The German Chainsaw Massacre (1990), High Tension (2003), House of 1000 Corpses (2003), Wrong Turn (2003), The Ordeal (2004), Them (2006), The Flesh Keeper (2007), Frontier(s) (2007), King of the Hill (2007), Slasher (2007), Storm Warning (2007), Timber Falls (2007), The Woods Have Eyes (2007), Backwoods (2008), The Cottage (2008), Eden Lake (2008), The Cycle (2009), The Hills Run Red (2009), Macabre (2009), Territories (2010) and Escape from Cannibal Farm (2017), among others, while the genre was parodied in Severance (2006) and Tucker and Dale vs Evil (2010).

Like Night of the Living Dead, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre redefined horror by stripping it of all classical motive. The assaults in the film come without rhyme or reason. Leatherface is not a monster of science or a demonic conjuration, he is even bereft of the cursory psychological explanations that the killers had in psycho-thrillers of the last decade such as Psycho (1960) or What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962) and their numerous imitators. In this sense, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre operates not unlike the bird attacks in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963), the zombies in Night of the Living Dead or the truck assault in Steven Spielberg’s Duel (1971) where such attacks come stripped of raison d’etre and in doing so evoke an undeniable existential anxiety.

These are also films stripped of all classical expectations – there are no classic guarantees of a handsome hero coming to save the heroine, no guarantees of a happy ending where Leatherface will be struck down by a lightning bolt. As in Night of the Living Dead, not even being cast as the hero is any guarantee that one will survive the film.

Equally so, Tobe Hooper has thrown out all conventions of horror technique – there are no build-ups of suspense, no edgy string underscoring as the characters enter the farmhouse. The brutal surprise of the attack on William Vail, with Leatherface just appearing from behind a hidden door, slamming him on the forehead with a sledgehammer and leaving him there twitching, while moments later Teri McGinn is thrown up on a meathook is something that almost over before one is aware of what is happening and leaves audience startled.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is all-out and no holds barred horror, a full frontal dive into a naked assault on its central character. The half-hour long attack on Marilyn Burns, which consists of nothing on the soundtrack bar screams and the buzz of a chainsaw, while the camera wildly careers in on extreme closeups of screaming throats and wide-open eyeballs, has the jagged ripped-open edge of a bad acid trip. You can literally feel Marilyn Burns’s sanity fraying at the assault.

Tobe Hooper seems to have set out to wear down one’s nerves from the outset. Within a matter of the first few minutes, the Hitch-Hiker appears out of nowhere – Edwin Neal appears clearly unbalanced at the outset then suddenly cuts his wrist with a razor, sets a photo on fire in the van and slashes crippled Paul Partian’s wrist, before jumping out and running off. This is only the first five minutes of the film and it has the effect of grinding an audience down in foreboding about what is to come. So too is the killing of three characters one after the other only about a third of the way through, which leaves one fearfully uneasy as to what might be in store for the remainder of the film.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre even manages to make its amateurishness work for it, with the crude photography and editing succeeding in giving the film an even more ragged and raw edge that a more professional production would have lost. (Although, one wishes some of the awful babyish gibbering and whimpering of Paul Partain’s performance would have ended on the cutting room floor). It is disturbing and not an easy film to like.

Tobe Hooper also borrows a promotional gimmick from The Last House on the Left and in the opening moments makes an entirely untrue claim that The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is based on events that happened in Texas. The closest The Texas Chain Saw Massacre comes to real events would be the exploits of the true-life Wisconsin necrophile and multiple murderer Ed Gein. The amazing interior decoration of the house by Bob Burns and Leatherface and his mask of human skin is clearly drawn from the story of Ed Gein who built furniture out of bone and skin and even wore human body parts but that is the sole connection to fact. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was one of several films that claim to be based on the exploits of Gein. Others claiming this basis are Psycho and The Silence of the Lambs (1991). Films that attempt to depict Ed Gein’s story are the excellent Deranged (1974), the disappointing Ed Gein (2000) and the heavily fictionalised Ed Gein: The Butcher of Plainfield (2007), while the shooting of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is depicted in episodes of Monster: The Ed Gein Story (2025).

There were several sequels to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre :– Tobe Hooper’s own underrated and surprisingly good The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986); the dull and formulaic Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre III (1990); and Texas co-writer Kim Henkel’s occasionally interesting The Return of the Texas Chainsaw Massacre/The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: A New Generation (1994). Continuity-wise all three sequels operate independent of and frequently contradict each other. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003) was an unnecessary but surprisingly watchable remake, which also spawned a prequel to the series with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning (2006). Texas Chainsaw (2013) was a further sequel to the original and was followed by a prequel Leatherface (2017) and another sequel Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2022) and another sequel Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2022). Texas Chainsaw Massacre: A Family Portrait (1988) and Texas Chain Saw Massacre: The Shocking Truth (2000) are documentaries about the making of Texas Chain Saw, while the making of the film is also discussed in the horror film documentary The American Nightmare (2000) and partly dramatised in the documentary Rondo and Bob (2020). The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was parodied in Hollywood Chainsaw Hookers (1988), Transylvania Twist (1989) and Stan Helsing: A Parody (2009).

Tobe Hooper’s subsequently made the dull Eaten Alive/Deathtrap (1977), which was an attempt to repeat The Texas Chain Saw Massacre that failed to find the same success. Hooper then began to move towards the mainstream with the fine tv adaptation of Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot (1979) about a town being overrun by vampires and the worthwhile slasher film The Funhouse (1981), before having his greatest success with the Steven Spielberg-produced ghost story Poltergeist (1982). Hooper went onto the enjoyable psychic alien vampire film Lifeforce (1985), the remake of Invaders from Mars (1986) and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986), all for Cannon Films. In the 1990s and up until his death in 2017, the slump of Tobe Hooper’s career has been sad to see, his work having included the dire pyrokinesis film Spontaneous Combustion (1990), the haunted dress tv movie I’m Dangerous Tonight (1990), an episode of the John Carpenter anthology Body Bags (tv movie, 1993), the erotic film Night Terrors (1993), an awful Stephen King adaptation The Mangler (1995), the weird apartment dwellers black comedy The Apartment Complex (1999), Crocodile (2000), the remake of Toolbox Murders (2003), Mortuary (2005) and Djinn (2013), as well as work on various genre tv series.

Co-writer Kim Henkel later went on to direct/write the third sequel The Return of the Texas Chainsaw Massacre/The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: A New Generation (1994). Henkel also co-wrote Tobe Hooper’s Eaten Alive/Death Trap (1977), created the story for the horror film The Unseen (1981), wrote/produced the non-genre Last Night at the Alamo (1993), co-produced the horror film The Wild Man of the Navidad (2008), wrote/produced the horror film Butcher Boys (2012) and produced Found Footage 3D (2016). Henkel is currently a film studies professor in Texas.

Trailer here