(Jungfrukällan)

Sweden. 1959.

Crew

Director – Ingmar Bergman, Screenplay – Ulla Isaksson, Based on the 14th Century Swedish Legend, Photography (b&w) – Sven Nykvist, Music – Erik Nordgren, Makeup – Börje Lundh, Sets – P.A. Lundgren. Production Company – Svensk Filmindustri.

Cast

Max Von Sydow (Töre), Birgitta Valberg (Märeta), Birgitta Pettersson (Karin), Gunnel Lindblom (Ingeri), Axel Düberg (Thin Herdsman), Ove Porath (Boy), Tor Isedal (Mute Herdsman), Allan Edwall (Beggar)

Plot

14th Century Sweden. The farmer Töre sends his innocent virginal daughter Karin to deliver candles to the bishop for Good Friday mass. However, Karin is late rising in the day, feigning the excuse of illness. Sent along with her is the other daughter Ingeri who is in disgrace because she is pregnant and unwed. Along the way, they encounter three goat herdsmen who claim poverty. Karin is moved to stop and offer to share her lunch with them, only for them to turn and rape her. Ingeri witnesses this but, resentful of Karin’s good graces, does nothing as the herdsmen kill her. The herdsmen then travel on, coming to Töre’s home. Unaware that he is Karin’s father, they claim poverty and ask to stay the night. When they offer Karin’s dress as a gift, Töre realizes they have killed her and is driven to take a violent and terrible revenge.

Sweden’s Ingmar Bergman (1918-2007) was one of the great directors of the 20th Century. Bergman’s films radiate an intellectual depth that stands heads and shoulders above the mass entertainment of everything else made around the world at the time. Bergman looked deep inside the philosophical and religious crises of the age and asked profound questions. Bergman was raised in a Lutheran family with a father who was a minister. He lost his faith at a young age and anger over religious dogma and petty bourgeoisie thinking runs throughout much of his work.

By the time he came to The Virgin Spring, Ingmar Bergman had already made 25 films and had started to accrue international acclaim. The Virgin Spring can be placed inside a loose thematic trilogy of Bergman’s films that began with The Seventh Seal (1957), a sonorous and weightily brilliant work in which a gloomy knight, played by Max Von Sydow, takes on Death in a chess game in an effort to stave of his own mortality, and then The Magician/The Face (1958) about an ambiguous group of travelling magicians whose presence upsets a staunchly religious household. All three films star Max Von Sydow and ask sombre questions about faith and religion.

The greatest fame that The Virgin Spring has today is that it gave uncredited inspiration to Wes Craven’s first film The Last House on the Left (1972). The influence is unmistakeable to the point that you could call The Last House on the Left an unacknowledged remake of The Virgin Spring. Craven virtually transplanted the entire story – two innocent girls fall astray of three psychopaths who rape and kill them, before the three killers travel on to seek refuge at the family’s home where the family, after discovering that the real identity of the three killers, exact a grim revenge against them. Craven did eliminate several aspects from The Virgin Spring, in particular the Christian symbolism that plays throughout and the miraculous redemption ending. Wes Craven’s film is also a good deal more barbed than The Virgin Spring – in The Last House on the Left, the vengeance the family exacts is not a just one but rather is seen as even worse than the acts that the three psychopaths conducted in the first place.

The rape scene takes place with hyper-emphasized detail. There is no music or dialogue throughout the scene, only incidental sound effects – the wind and the river, the stone being dropped, the goatherds stomping on the candles. Of course, the rape and vengeance enacted is much tamer than the grimness with which similar things are depicted in The Last House on the Left, and other modern rape/revenge films like Straw Dogs (1971), Day of the Woman/I Spit on Your Grave (1978) and Irreversible (2002). Nevertheless in the strength of the emotions brought out, there is a powerful sense of the grief and the terribleness of the actions that Max Von Sydow gives himself over to.

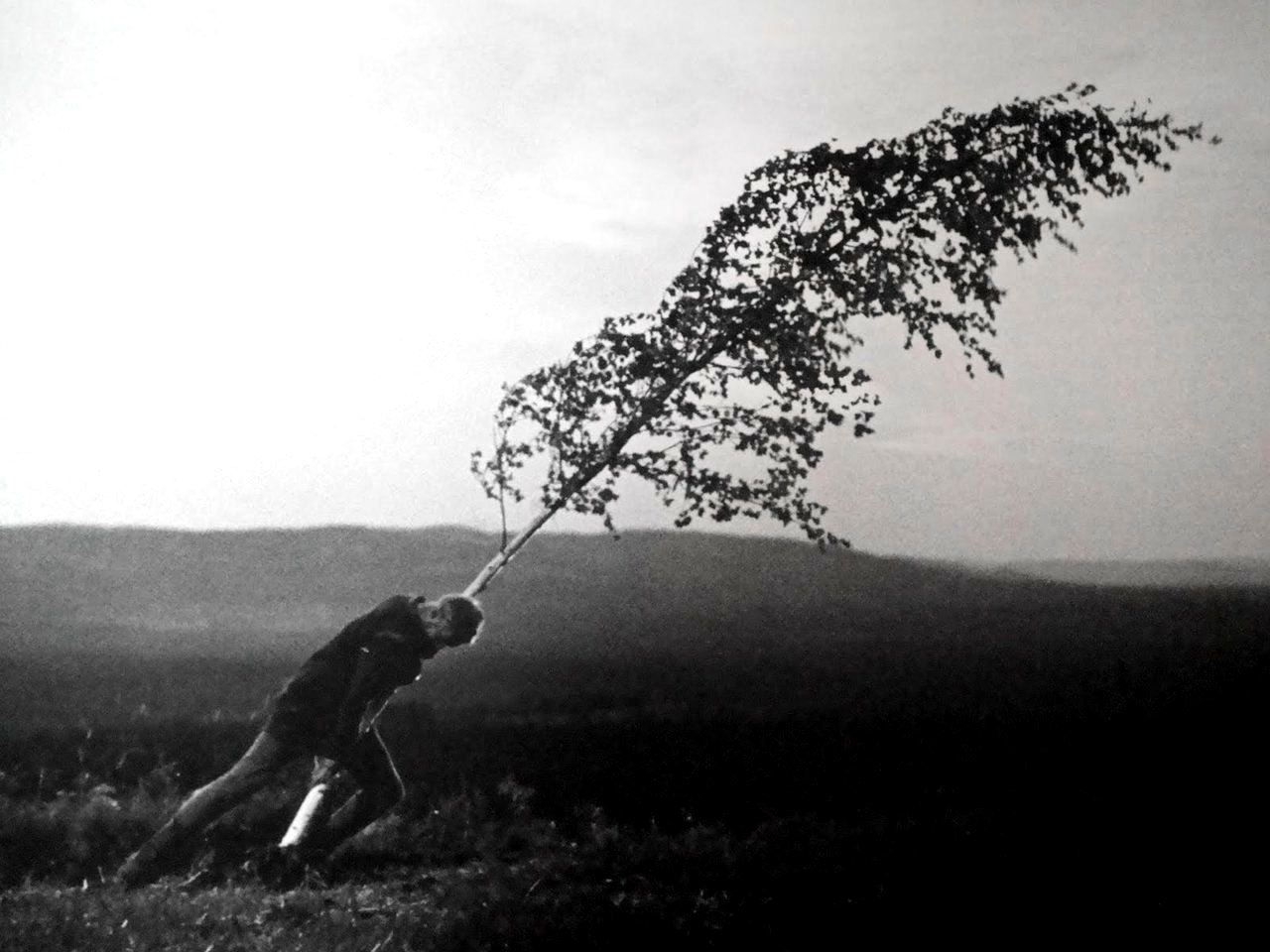

The Virgin Spring is almost overripe in symbolism. There is the incredibly stark scene, one that is frequently reproduced as a still, where Max Von Sydow wrestles a sapling to the ground. Birgitta Pettersson is painted from the opening scenes as an innocent who heading for a big fall. She is shown as petulant and self-absorbed, lying in bed feigning illness because she has in fact been out the previous night dancing with boys. Her breezy innocence is contrasted against the staunch but virtuous Christian household that believes in the Christian work ethic. From the outset, Ingmar Bergman stuffs everything with ominous warnings:

“If you always get your own way, you’ll please The Devil so much the saints will punish you with toothache,” her mother warns.

“Why do you talk so much of The Devil?”

“Because The Devil is the seducer of the innocent. He strives to destroy all goodness.”

The two sisters are played as psychic opposites. Karin represents a virtuous innocence and is upheld by the family; whereas Ingeri represents the polar opposite – she is pregnant, castigated by the family and, where Karin believes in girlish romance, she sees only clumsy ruttings. To emphasize the contrast, Karin is even blonde, while the fallen Ingeri is raven-haired. Not merely content to dally with Christian faith, Bergman also throws in a good deal of pagan symbolism – the sister’s rape could well have been a result of Ingeri’s praying to the god Odin that we see at the very start and there is much made of the symbolism of the coming of spring and reference to the departure of the May Queen.

The Virgin Spring can also be seen as Ingmar Bergman’s concluding chapter in a thematic trilogy about faith, coming after The Seventh Seal and The Magician. With The Seventh Seal, Bergman looked at the world around him and saw only pain, suffering and death and wondered where God was in all of this; in The Magician, he saw that illusion and magic held a necessity and vitality in contrast to religious dogma and scientific reductionism. By the time of The Virgin Spring, Bergman has scoured the darkest possible places – here he reduces a virtuous Christian man (Max Von Sydow, his stand-in in all of these films) to a murderer – but contrary to the overriding atheism he would seem to espouse elsewhere, Bergman comes out of The Virgin Spring seeking Christian redemption.

The film arrives at an interesting ending. After killing the three goatherds, Max Von Sydow rails against God for allowing this to happen – both in regard to the rape and in allowing his anger its full flow. The dead daughter’s body is taken and placed in the woods where it is announced that a church will be built upon this spot in an attempt to expiate the terrible things that have happened. Just as they lift the daughter’s dead body, a spring miraculously flows forth from the spot where the body was lying. Everyone looks thankfully heavenward as the camera pans upwards in the fadeout. The Virgin Spring is the most hopeful of these three films, even if it is one that sees Ingmar Bergman returning to a belief in the very Christianity he dismisses as false and dogmatic almost everywhere else.

Ingmar Bergman’s other ventures into fantastic cinema have been:– The Seventh Seal (1957), a staggering and profound meditation on religion with a knight meeting with Death; The Magician/The Face (1958), about a magical performing troupe who have reputed supernatural powers; The Devil’s Eye (1960), a comedy about The Devil sending Don Juan to tempt a vicar’s wife whose purity offends him; Hour of the Wolf (1968) about a tormented artists’s hallucinations come to life; the acclaimed adaptation of Mozart’s opera fantasy The Magic Flute (1975); and the family saga/ghost story Fanny and Alexander (1982). All are recommended with the highest praise.