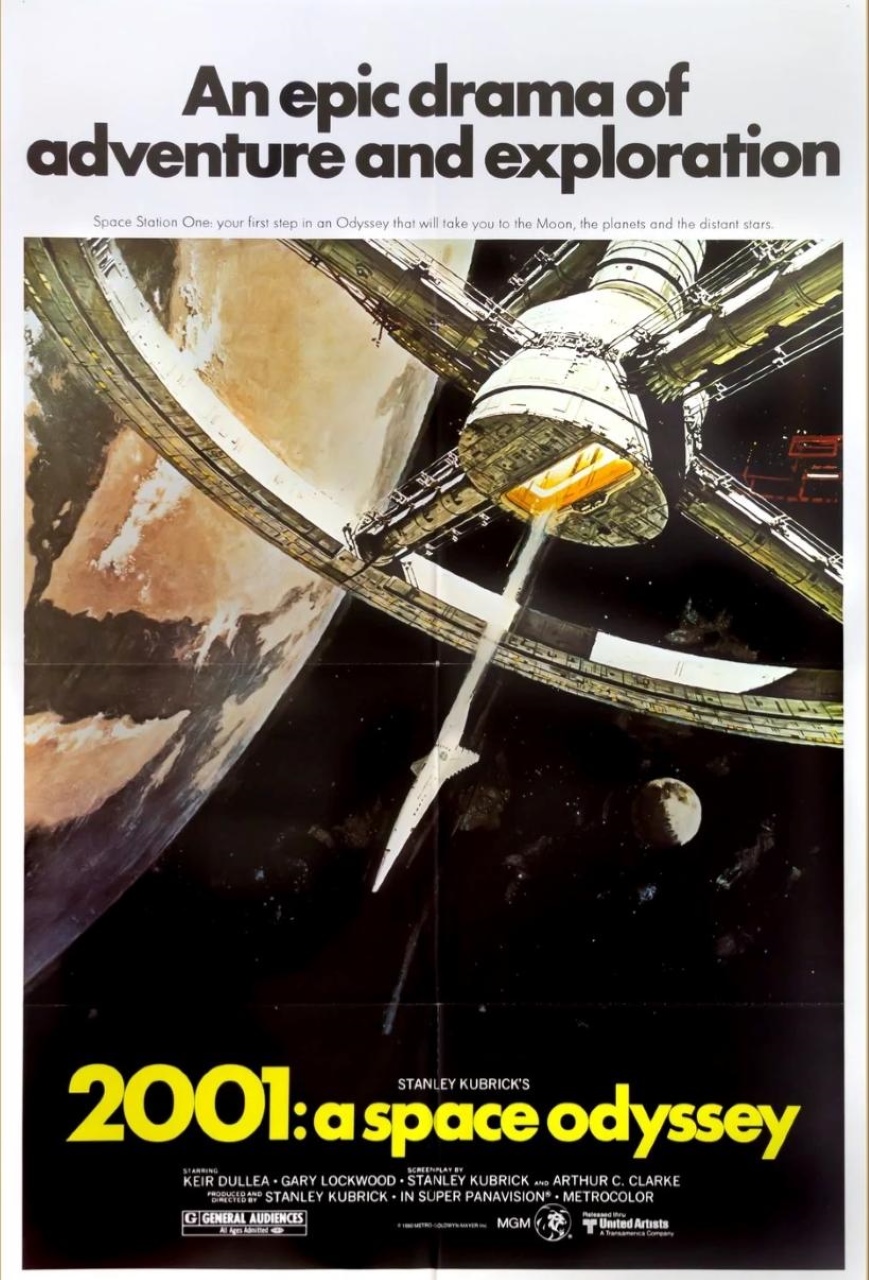

USA. 1968.

Crew

Director/Producer/Photographic Effects Designer & Director – Stanley Kubrick, Screenplay – Arthur C. Clarke & Stanley Kubrick, Based on the Short Story The Sentinel (1953) by Arthur C. Clarke, Photography – Geoffrey Unsworth, Music – Alex North, Photographic Effects Supervisors – Con Pederson, John Howard, Douglas Trumbull & Wally Veevers, Makeup – Stuart Freeborn, Production Design – Ernest Archer, Harry Lange & Tony Masters. Production Company – Polaris/MGM.

Cast

Keir Dullea (David Bowman), Gary Lockwood (Frank Poole), Douglas Rains (Voice of HAL 9000), William Sylvester (Dr Heywood Floyd)

Plot

An enigmatic black monolith appears at the dawn of human history, teaching primitive man the use of tools. In the 21st Century, Dr Heywood Floyd travels to Clavius Base on the Moon where the colonists have uncovered an identical monolith in a lunar crater. As soon as the monolith is uncovered, it sends a signal to another monolith in orbit around Jupiter. The spaceship Discovery is sent to Jupiter to investigate but the mission is sabotaged in mid-voyage by HAL 9000, the ship’s paranoid computer. A sole astronaut David Bowman survives to make his way to the monolith, which proves to be a stargate that propels him on an intergalactic journey to an experience that will take him up the next step on the evolutionary ladder.

Is 2001: A Space Odyssey the greatest science-fiction film ever made? Many people consider it such – it is the only science-fiction film to feature in the critics poll run every decade by Sight and Sound magazine, for instance. There would be few All-Time Best Lists from science-fiction genre critics that 2001 would not appear on. Although equally there have also have been a number of dissenting voices.

Many of the science-fiction fans from the Star Wars (1977) generation lack the patience for 2001 – it is not adrenal adventure, it is slow-paced, its’ meaning is cloudy and it does not spell out everything in pat moral epithets. 2001: A Space Odyssey is a film that defies all that is supposed to make good storytelling – there are about four different stories going on, not all of which seem to connect up with one another; there is approximately only twenty minutes of actual dialogue in the film, most of which consists of banal exchanges that have little to do with carrying the plot; and it is a film that offers no clear explanation of what it is about, rather it demands that we piece meaning together out of the clues it gives us.

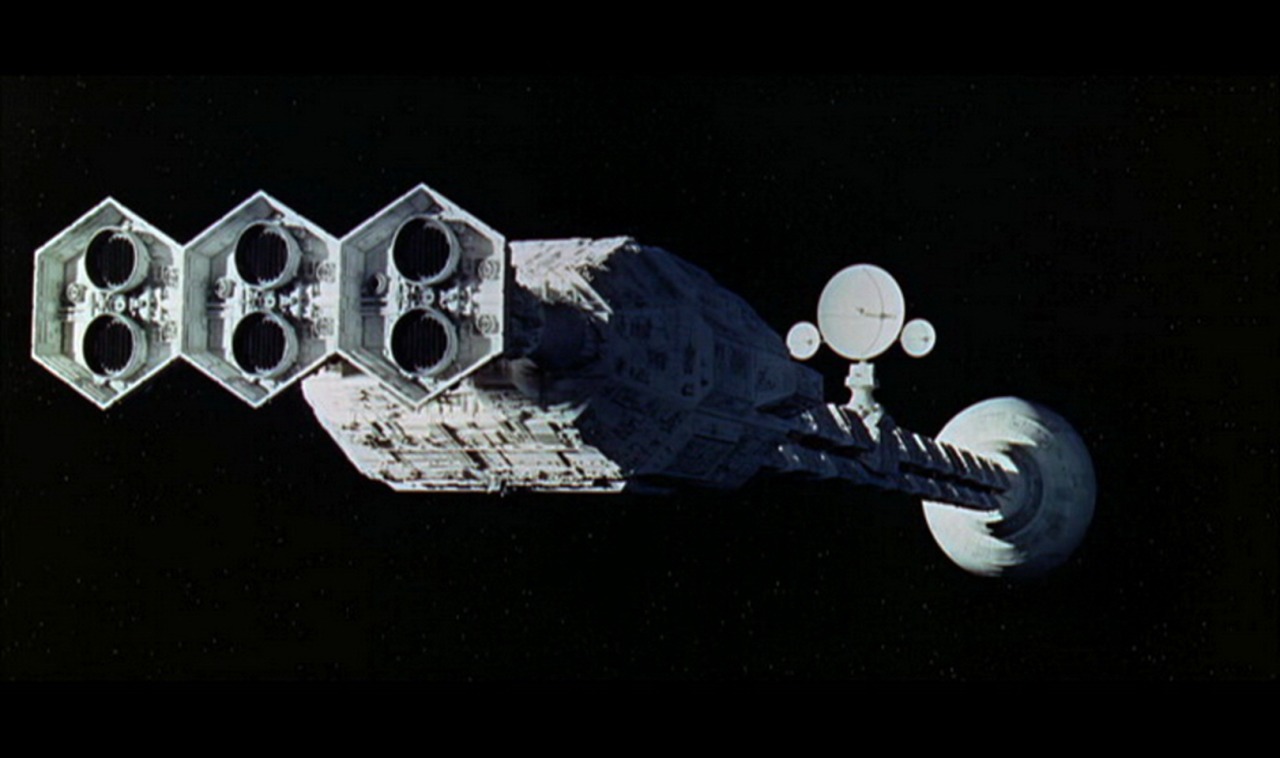

Stanley Kubrick, in interviews, stated that he wished 2001: A Space Odyssey to be a visual experience that circumlocutes the rational and that meaning should only be imposed in an existential sense. Interpretations have varied between the intelligent and the merely fatuous – those that have seen all the space-docking manoeuvers, the spermatozoa-shaped Discovery and the embryonic imagery in terms of Freudian symbolism – to those that have countered that Stanley Kubrick only said this to hide the fact that the film isn’t about anything at all.

At the time that he made 2001: A Space Odyssey, Stanley Kubrick had risen as a director through some competent thrillers, Fear and Desire (1953), Killer’s Kiss (1955) and The Killing (1956), and found a name with the war film Paths of Glory (1957) and the epic Spartacus (1960), before making the highly controversial Lolita (1962) about paedophilia. Kubrick then found enormous acclaim with Dr Strangelove; or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), a biting black comedy about the nuclear end of the world. Stanley Kubrick’s collaborative partner on 2001: A Space Odyssey was Arthur C. Clarke, a celebrated British science-fiction author who had had some rare crossover success into the mainstream at a time when the science-fiction was still fairly much in a pulp ghetto with books like Childhood’s End (1953), Earthlight (1955), Against the Fall of Night (1956), The City and the Stars (1956) and A Fall of Moondust (1961).

2001: A Space Odyssey‘s scope is the widest of any science-fiction film. There is no other film then or since that depicts humanity’s future in space with such matter-of-fact realism. Even more impressive is the conceptual grandiosity of the story – it begins with the moment that humanity first defined the difference between it and an ape and ends with a human being climbing up the next rung on the evolutionary ladder. In a shot that must be one of the most parodied in cinema history, Stanley Kubrick conducts a cut from a bone thrown by a caveman twirling up into the air in slow-motion to a satellite in orbit in freefall. The sheer audacity of a shot that can cover the whole way of human evolution in one twenty-fourth of a second, from the very first tool-maker to humanity among the stars, is staggering.

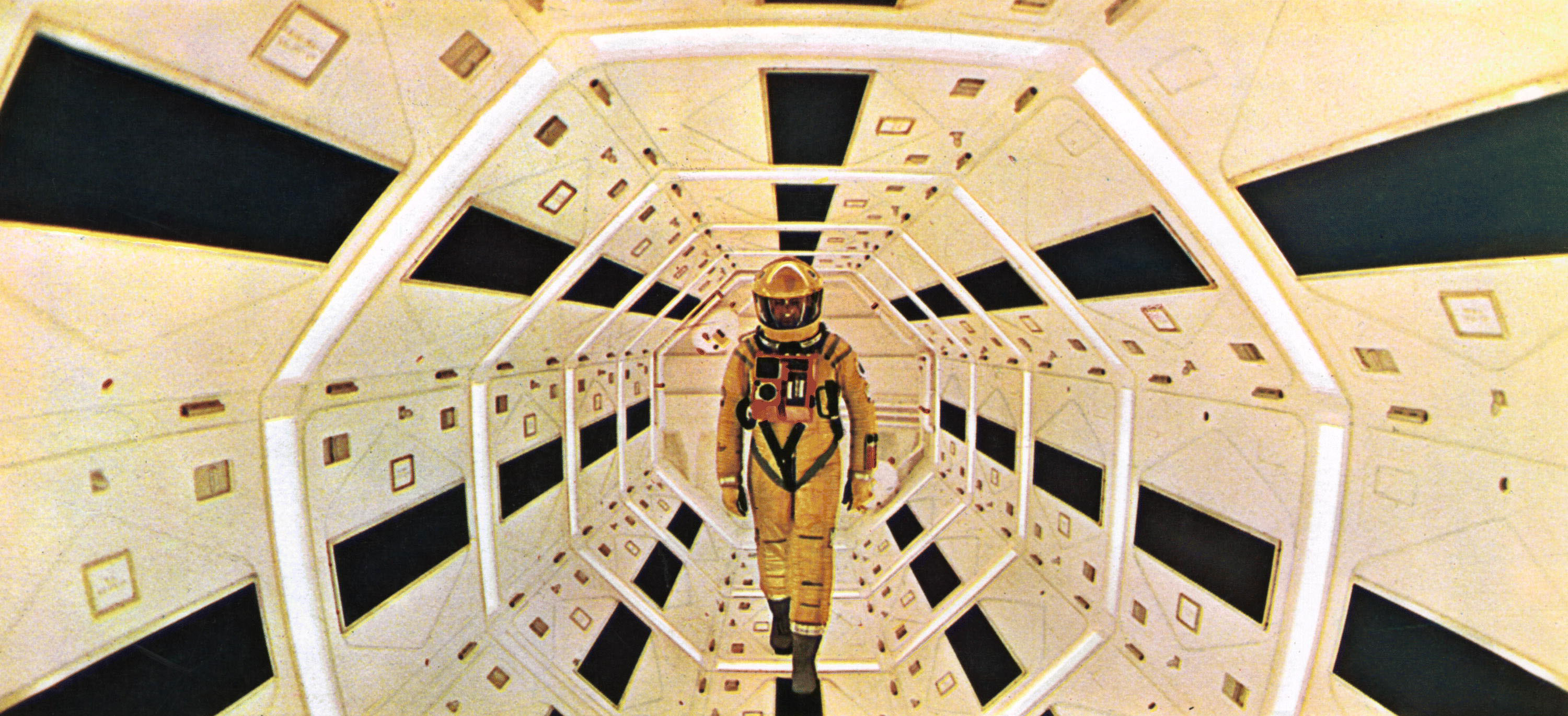

This is perhaps why 2001: A Space Odyssey is so acclaimed by mainstream critics – it is one of the most eminently visual of all science-fiction films. Spaceflight had been depicted on screen before but never with such realism – there is the breathtaking visual poetry of the scenes where Stanley Kubrick shows us the docking with a space station and Moon landing where spaceships gracefully twirl and dock in freefall all to the sweep and lull of Johann Strauss’s Blue Danube waltz. This is why 2001: A Space Odyssey is great as science-fiction because it is a demonstration of what science-fiction can conjure in the visual medium – the abovementioned scenes would be impossible to create via the written word. Indeed, Arthur C. Clarke’s novel of the film published at the same time fails to deliver any of the visual poetry of the film.

The final sequence of the film, entitled Jupiter: Beyond the Infinite, is where 2001: A Space Odyssey gained its slow reputation as a head film (one best seen under the influence of drugs) on the campus circuit in the mid-seventies. (2001: A Space Odyssey was not hugely success during its initial release). In these scenes, Stanley Kubrick takes us on a hypnotically beautiful journey – through tunnels of light; across primordial starscapes and embryonic organic forms; sonorous flights across alien landscapes (represented simply but most effectively by aerial shots cruising across coastal/oceanic landscapes all tinted with red, blue and yellow filters). One has the sense that they are indeed experiencing a journey into wholly alien realms. In the decade to come, these psychedelic lighting effects would become an overused effect to represent a transcendental journey, but when seen here the effect still remains one of hypnotically soothing beauty.

The great talking point of the film is the arrival at the cold, eerily underlit hotel room where Keir Dullea keeps seeing older versions of himself before another monolith appears and he transforms into the Star-child, coolly looking down on the Earth. All audiences want to know what it means. The best clues come in reading Arthur C. Clarke’s The Lost Worlds of 2001 (1975), which contains many of the originally discussed ideas for the stargate journey that did not end up being used – all contain the recurrent idea of Bowman being accepted into an intergalactic brotherhood – and contrast these with the version that did originally end up on screen. It gives insight to what the film is trying to say. Certainly these other ideas seem much more lavish and much more literalistic than what we did end up with. In the end, Stanley Kubrick appears to have opted for a much more enigmatic and surreal representation, as though to say such an experience would necessarily be beyond the possibility of literal depiction.

2001: A Space Odyssey was a meeting between two great talents. It is both a melding of both similarities and disparities. (The story is nominally based on Arthur C. Clarke’s short story The Sentinel (1951), although this only covers the sequences on the Moon). Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke were both technically obsessed – Kubrick was obsessed with the exacting technical perfection for the crafted image and had a reputation for demanding a reputed 150+ takes of a shot and of building complex detailed sets; while Arthur C. Clarke was the most pre-eminent of the school of hard science-fiction writers whose work was founded on logical scientific extrapolation.

Both are also cold when it comes to people – Clarke is simply indifferent to them, his characters are never more than names on a page; Kubrick regards people with a minatory cruelty – he is a cynic when it comes to humanity or else his films seem like giant stage sets where the camera remains at a detached distance while actors barnstorm with theatrical regard. There is never in Stanley Kubrick’s films what might be described as warmth or sympathy toward his characters – when there is, such as with Malcolm McDowell in A Clockwork Orange (1971), it is all part of a gigantic black joke to make us feel sympathy for someone reprehensible. In 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick deliberately plays into Arthur C. Clarke’s woodenness of characterisation in ways that Clarke probably never intended. The film is virtually bled dry of its humanity – the dialogue consists of banal disinterested exchanges and the human characters are blank cutouts that have been bled of any vitality.

For all its enthusiasm for the wonders of the universe it takes in, 2001: A Space Odyssey is a film with a deep-seated cynicism about humanity and technology. The great irony about the first breakthrough in human evolution and the discovery of using a bone as a tool is that the first thing humanity uses it to do is bash his fellow man’s brains out with. The breathtaking grandeur of the bone-to-spaceship cut is underlaid by the inherently understated cynicism that seems to be saying that no matter how sophisticated our tools become they are only variations on that first bone.

The principal thesis throughout the space station and Jupiter mission sequences, even more so than the wonderment of being in space, is that humanity has become strangled by its technology. In space the only difference between life and death in frozen sarcophagi is that of lines flattening out on a monitor. The great irony of the film is that the most human of the characters is actually the least – the computer HAL 9000 given a beautifully silky, seductive voicing by Douglas Rains. His final pleading “Dave, I’m losing my mind” is far more memorable than the death scene of Gary Lockwood. Stanley Kubrick’s message here is that our tools will eventually become so sophisticated they will come to enclose and dehumanise us before eventually deciding they don’t like the way we run things.

You can argue that the bleakness of of 2001‘s vision of humanity is simply Stanley Kubrick laying his customary cynicism on Arthur C. Clarke’s woodenness of characterisation. On the other hand, the parts of 2001: A Space Odyssey that remain the most distinctively Clarkeian is its visionary transcendence. Arthur C. Clarke’s work is rooted solidly in science. In an earlier era, you could imagine Clarke having been the equivalent of a Giotto or a Michelangelo, depicting the reach between man and the divine, but as a product of the twentieth century Clarke is instead a writer depicting the awe of the scientifically explainable universe. His work, despite his inherent atheism, is some of the most religious of all science-fiction. His books – Childhood’s End, Imperial Earth, The Songs of Distant Earth – feature characters caught on the cusp of a transcendental breakthrough in consciousness; and Rendezvous with Rama, probably his single greatest work, reads like a walk through a single giant cathedral of technology. Even more directly, Clarke has written playful works like The Nine Billion Names of God (1953) and The Star (1955), which offer explanations of the universe that directly connect in a meeting place between religion and science. The rest of Stanley Kubrick’s work is not exactly noted for its religious mystery – in this case, what made 2001: A Space Odyssey great seemed like a director with a stunning grasp of cinema connecting perfectly with one writer’s vision of the universe.

What is especially notable about 2001: A Space Odyssey is the subsequent changes it wrought in science-fiction. Up until Star Wars, 2001: A Space Odyssey was the benchmark against which all other science-fiction films were measured. It was a demarcation line after which science-fiction was never the same again. Left behind was all of 1950s science-fiction, trembling at alien invaders and at most conducting tentative fear-ridden space operatic journeys to other worlds only to end in disaster or be turned back by unwelcoming aliens there. In its place we subsequently had science-fiction visions that sought after epic, transcendental states of mind and the universe – works like Solaris (1972), Zardoz (1974), Phase IV (1974), tv’s Space: 1999 (1975-7), The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), Stalker (1979), The Black Hole (1979), Star Trek – The Motion Picture (1979), Altered States (1980), Brainstorm (1983), Akira (1988), Mission to Mars (2000), The Fountain (2006), Enter the Void (2009), Beyond the Black Rainbow (2010) and Interstellar (2014). In the decade to come, other films would run with the 2001 look – the likes of Colossus: The Forbin Project (1969), The Andromeda Strain (1971), THX 1138 (1971), Chosen Survivors (1974), The Terminal Man (1974), Rollerball (1975), Coma (1978) and Brave New World (tv, 1980) – to create a vision of the future where technology had strangled humanity to the point that people had become like a disease blemishing science triumphant’s antiseptic perfection.

Stanley Kubrick’s other genre films are:– the nuclear war black comedy Dr Strangelove; or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964); A Clockwork Orange (1971) about near future violence and brainwashing; the Stephen King haunted hotel adaptation The Shining (1980); and Steven Spielberg’s A.I. (Artificial Intelligence) (2001), adapted from a long-time Kubrick project following Kubrick’s death in 1999. Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures (2001) is a fascinating documentary about Kubrick and his body of work. Operation Avalanche (2016) is a Found Footage film about the faking of the Moon Landing and contains an amusing scene where the filmmakers visit the exactingly recreated set of 2001 in an effort to recruit Stanley Kubrick.

In the 1980s, where science-fiction became for the first time a mainstream publishing phenomenon, Arthur C. Clarke joined a number of other veteran science-fiction writers – including Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, Larry Niven and Harry Harrison – in churning out commercially-driven sequels to his previous books. Amid this, Clarke produced three banal 2001 sequels – 2010: Odyssey Two (1982), 2061: Odyssey Three (1988) and 3001: The Final Odyssey (1997). The first of these was filmed as 2010 (1984) by Peter Hyams and, although critically condemned for the impertinence of trying to be a sequel to 2001, is a fine film in its own right. Numerous Arthur C. Clarke projects have been considered for filming over the years – Dolphin Island, A Fall of Moondust, with Childhood’s End and Rendezvous with Rama (particularly the possibility of an adaptation from David Fincher) being the most persistent – but the only other Clarke adaptations to have made it to the screen has been the passable tv movie Trapped in Space (1994) and the eventual, heavily disappointing tv mini-series adaptation of Childhood’s End (2015). After 2001: A Space Odyssey, Arthur C. Clarke’s popularity was such that he was made into the CBS co-host of the Apollo 11, 12 and 15 missions and of the tv series Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World (1980-2) dealing with the unexplained.

2001: A Space Odyssey is parodied in Schlock (1973), The Big Bus (1976), Simon (1980), The Creature Wasn’t Nice (1981), Airplane II: The Sequel/Flying High II: The Sequel (1982), Cannibal Women in the Avocado Jungle of Death (1989), National Lampoon’s Men in White (1998), 2001: A Space Travesty (2001), Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005), National Lampoon’s Homo Erectus (2007), Be Kind Rewind (2008), Wall-E (2008), Planet 51 (2009) and Farmageddon (2019).

Trailer here