USA/UK. 2001.

Crew

Director – Peter Howitt, Screenplay – Howard Franklin, Producers – Keith Addis, David Nicksay & Nick Wechsler, Photography – John Bailey, Music – Don Davis, Visual Effects Supervisor – Patrick Shearn, Visual Effects – Matte World Digital, Metrolight Studios Inc & Rainmaker Digital, Special Effects Supervisor – Gary Minielly, Makeup Effects – Kevin Haney, Production Design – Catherine Hardwicke. Production Company – Hyde Park Entertainment/Industry Entertainment.

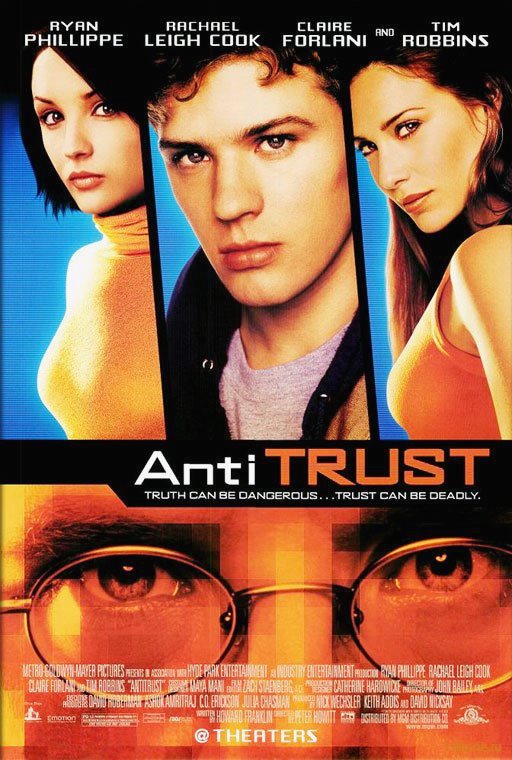

Cast

Ryan Philippe (Milo Hoffman), Tim Robbins (Gary Winston), Claire Forlani (Alice Poulson/Rebecca Paul), Rachel Leigh Cook (Lisa Calighan), Douglas McFerran (Bob Schrott), Ned Bellamy (Phil Grimes), Richard Roundtree (Lyle Barton), Yee Jee Tso (Teddy Chin), Nate Dushku (Brian Bissel), Tygh Runyan (Larry Banks)

Plot

Young Milo Hoffman is a genius programmer with a small garage-based group of friends hoping to make their big break as an internet start-up. Milo then receives a phonecall from Gary Winston, the all-powerful CEO of NURV, a computer corporation that is being accused of maintaining a ruthless stranglehold on rivals in order to become the mainstay in the software field. Winston wants Milo to come and work on Synapse, the planned satellite system that will deliver media to every laptop and handheld in the world. Milo agrees, despite his friends saying they would never work for a company that practices such tactics. However, when his friend Teddy is killed seemingly by racists, Milo discovers evidence that indicates that Winston is killing independent programmers and stealing their ideas.

When it came out, Antitrust had a torn-from-the-headlines urgency. It wanted us to, as far as it can do without naming names, believe it is a thriller about the Microsoft antitrust case that was going through US courts (and was not decided until after the film was released).

The film opens on such a trial and Tim Robbins is made up to look like Bill Gates and even gives inspirational speeches just like Gates does. If there is any doubt that Antitrust wants you to notice how much it has based its case on the Microsoft trial, just look at the title – the term ‘antitrust’ became a buzzword as a result of the Microsoft trial whereas in fact it is a relatively obscure (and rarely enforced) piece of US legal terminology that refers to anti-competitive practice in the marketplace ie. companies that are doing things to discourage fair competition (such as Microsoft building operating systems that make competitors software difficult to use).

The point being that Antitrust the film does not have a lot to do with antitrust in the legal sense of the meaning. The activities engaged in by the film’s equivalent of Microsoft are less anti-competitive than they are blatantly criminal – the outright theft of software and murder of the developers. There is a considerable leap between the two. Indeed, if Bill Gates were to ever sue Antitrust for libelling his name, he would have a fairly strong case. While Gates has without question engaged in ruthless and unsavoury business practices, his hands have yet to be bloodied with charges of murder or doing anything other than obtaining software patents in an orthodox manner.

The fact that Antitrust can get away with making the jump from calling Bill Gates a ruthless businessman to an outright criminal has less to do with creative license and more to do with the public perception of Gates as a villain. If you consider the fact that the real world Microsoft antitrust suit was still in the appeals stage when the film came out and not yet decided, the colour of the film’s characterisation of Gates is quite strong.

Antitrust is a competent thriller, no more than that. Up to this point, computer thrillers had tended to borrow the models of other films and have yet to create their own original form – Sneakers (1992), the best of these, was more of a hi-tech caper film a la Topkapi (1965); The Net (1995) was just an old-fashioned paranoia conspiracy film; while Hackers (1995) was nothing more than a pseudo-twentysomething slice of lifestyle film trying to tap into hacker/geek culture. Antitrust is no different – the model it takes is the story of the innocent being seduced by the powerful corporation as patented by the likes of The Firm (1993) and The Devil’s Advocate (1997).

For a time, Antitrust proves enjoyable. Tim Robbins does an amusing impression of Bill Gates and has considerable fun whenever he is on screen. Indeed, he is allowed to make some persuasive speeches that make his character seem sympathetic. If the film had stayed with this, it would have probably been more interesting. However, not long after, the story about a seduced innocent is thrown aside and we are propelled into standard suspense mechanics where Antitrust simply becomes a thriller about one person trying to find evidence of wrongdoing, one in which there are no longer any shades of grey in regard to the hero’s choices.

The thriller set-pieces range between the competently conducted – during Ryan Philippe’s break-in to the surveillance center – to the unintentionally risible – Philippe thinking Claire Forlani is plotting to kill him by cooking a dinner with sesame seeds in it. The ending where we realise that just about everybody in the principal cast has changed their initial alignment at least once collapses into ridiculous contrivation. To the film’s credit, it at least never sees the need to pump the action up with gratuitous car chases and shootouts.

The one thing that Antitrust does well is provide a credible picture of tech culture and working environments. Unlike other films such as The Net, Hackers and tv’s Bugs (1995-8) and Level 9 (2000), it is reasonably knowledgeable technically. (It has even hired science-fiction writer Gentry Lee as technical advisor). There are a lot of geek, if not exactly in-jokes, then asides: “You’ve got a real girlfriend,” one geek incredulously exclaims to Ryan Philippe. The film accurately depicts the fierce dislike of many hackers for Microsoft’s tactics and how working for Microsoft is equated with the ultimate sellout, and contrasts this with the struggle to survive as an independent start-up.

In the end though, box-office ultimately triumphs over believability – Ryan Philippe is far too pretty, far too socially astute and simply far too well-dressed to be a believable hacker. One of the film’s biggest plausibility holes is simply the film asking us to believe that a computer geek could ever pull in a babe like Claire Forlani.

The film ends on the same sort of naive hacker fantasy that Hackers did – of the truth being broadcast to the world (although the slick MTV/commercial style of presentation used would probably have it dismissed as propaganda by most) and the undeniable wish fulfillment fantasy of Tim Robbins’ Bill Gates stand-in being dragged off in handcuffs.

Antitrust was directed by Peter Howitt who previously made the romantic fantasy film Sliding Doors (1998) and would go onto the puerile spy comedy Johnny English (2003), the romcom Laws of Attraction (2004) and the post-holocaust film Scorched Earth (2018).

Trailer here