Crew

Director – Ridley Scott, Screenplay – Hampton Fancher & David Peoples, Based on the Novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick, Title Based on the Novel by Alan E. Nourse, Producer – Michael Deeley, Photography – Jordan Cronenweth, Music – Vangelis, Visual Effects – David Dryer, Douglas Trumbull & Richard Yuricich, Makeup – Michael Westmore, Production Design – Lawrence G. Paull & David L. Snyder. Production Company – The Ladd Co/Sir Run Run Shaw.

Cast

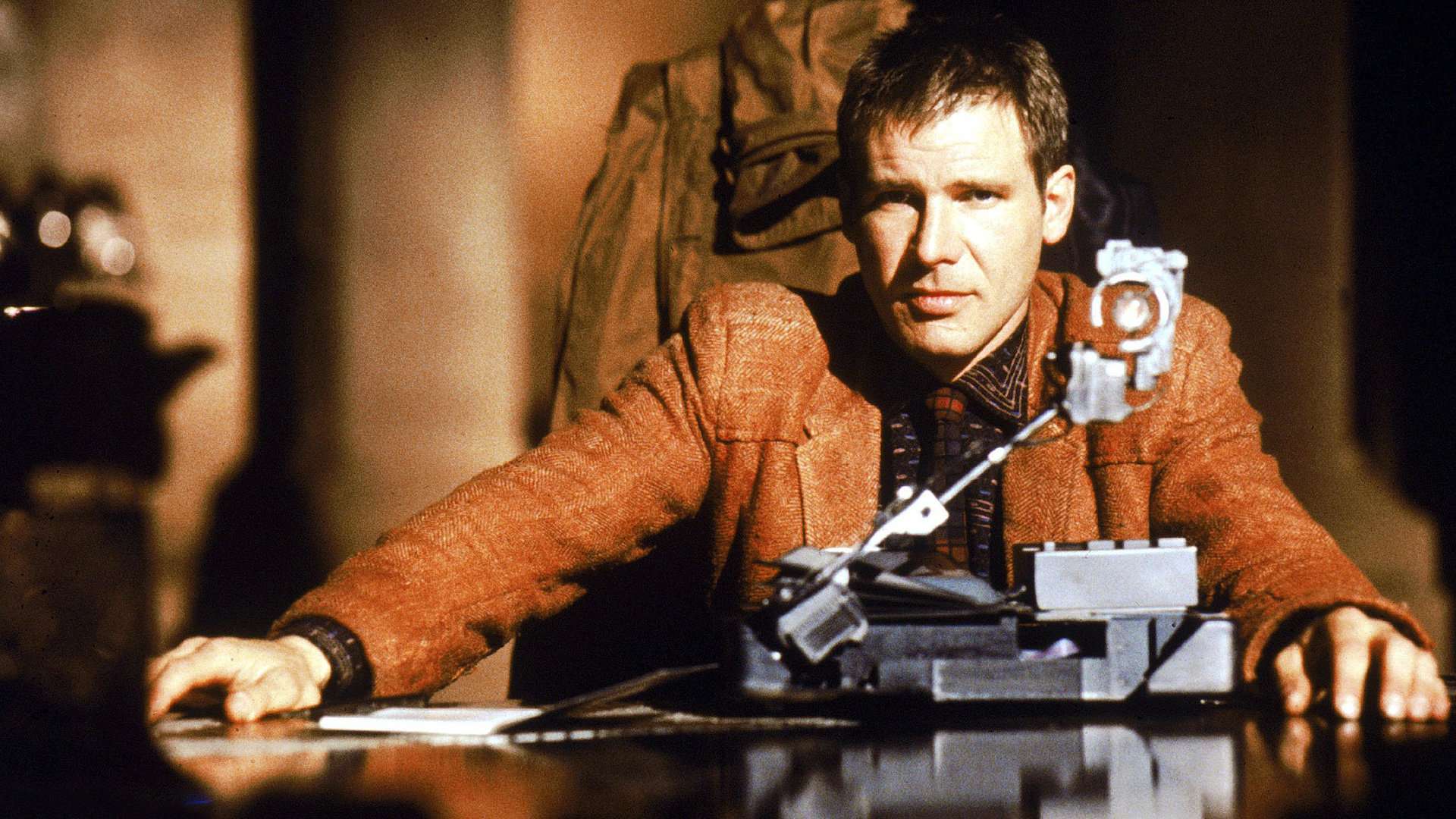

Harrison Ford (Rick Deckard), Rutger Hauer (Roy Batty), Sean Young (Rachel), Daryl Hannah (Pris), Brion James (Leon), Edward James Olmos (Gaff), Joanna Cassidy (Zhora), William J. Anderson (Sebastian), Joe Turkell (Tyrell), M. Emmet Walsh (Bryant)

Plot

Los Angeles of 2017. Rick Deckard is a blade runner – a bounty hunter that specializes in terminating replicants, androids so able to mimic human behaviour that they are indistinguishable from humans except in the mimicry of emotions (something that can only be detected by a test that measures reflexive responses to questions of an emotional nature). Deckard is called in by the police to hunt down four replicants escaped from an offworld colony and come to Earth in search of their creator to find a means of extending their built-in four-year lifespan. However, Deckard’s quest to find the replicants becomes one that makes him question his own humanity.

Blade Runner is one of the modern classics of the science-fiction genre. Blade Runner was the second landmark genre film from Ridley Scott who had previously created another film that had revolutionised the genre with Alien (1979). Blade Runner was adapted from Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1969), a novel by Philip K. Dick. Philip K. Dick was a writer who recurrently obsesses with questions of what is real and of characters finding that their lives are elaborate fabrications. Philip K. Dick was probably the cultiest of the science-fiction writers to emerge from the 1960s New Wave movement. Blade Runner was the first time that Dick had been adapted to film. (See bottom of the page for other Philip K. Dick film adaptations).

Both the film and the Philip K. Dick novel travel essentially the same road in telling the story of an emotionally barren man who hunts androids and comes to realise, ironically from creatures that only mimic humanity, what his own humanity means. However, both are very different texts. First of all, the film has thrown out Philip K. Dick’s title, which would admittedly be hard to fit on a cinema billboard, and in to little point comes the title of a little known 1974 science-fiction novel by Alan E. Nourse about a future where medicine was outlawed. Part of the reason for the title change could well be that the ‘electric sheep’ part no longer makes sense. In the book’s future, animals were virtually extinct and all but the rich had to make do with android replicas – it was Deckard’s greatest ambition to own a real sheep. The only remnants of this central theme come in vague references – Deckard’s question to Zhora “Is the snake real?” and her reply, “Do you think I’d be working in a place like this if I could afford one?”

Similarly, the purpose of the questions about animals to gauge responses during the empathy tests in the film becomes unclear unless you have read the book. Gone too, probably out of the cinematic difficulty of the idea, are the elaborate games where the androids try to make Deckard doubt his own reality, and Mercerism, the bizarre plug-in religion of shared suffering – one gets the feeling a proper translation of a Philip K. Dick book would be somewhere out in Luis Buñuel territory.

On the plus side, the film brings in some ideas that improve on the book – Batty, a bland character in the book, becomes a stronger protagonist, being given a wonderfully dynamic performance from Rutger Hauer; the idea of the four year lifespan gives the androids driving purpose; and Hampton Fancher and David Peoples have scaled the drama up into a series of exciting confrontations. Philip K. Dick was ecstatic about the script but sadly never lived to see the completed result, dying four months before the film’s release. The script is beautiful at times, Batty’s dying soliloquy “All the things I have seen; these shall be lost in time like tears in the rain” (apparently a line that was devised by Rutger Hauer himself according to Scott) surely stands as one of science-fiction cinema’s most eloquent.

Blade Runner‘s vision of the future is one of the most detailed put on film. Indeed, Blade Runner single-handedly changed the look of science-fiction on film. Unlike the pristine glass and plastic, kaftaned-populaced utopias of other futures up to this point in the likes of Logan’s Run (1976) and Things to Come (1936), this is the first screen future that was seen as a direct abstraction of the present. Punks and Hare Krishnas bustle shoulder to shoulder on streets where it always rains; ads for Coca-Cola and Atari and commercials in Japanese take up sides of entire buildings; a hovering blimp advertises the pleasures of going off-world. Prior to Blade Runner, science-fiction futures existed as vistas of spotless wonderment – cities where Utopian architectural marvels were shown stretching off into the distance; Blade Runner created a vision of the future that dripped with an excess of textural density and teemed with an entire implicit but never directly referred culture where you were deliberately given the impression that what the camera was seeing was only the tip of an iceberg.

In fact, Blade Runner pioneers much of the vision that became the staple of the Cyberpunk genre. William Gibson, who is credited with creating the essential shared vision of Cyberpunk, with its jacked-in, downbeat, texturally dense future, confessed that seeing Blade Runner nearly caused him to give up writing his seminal Cyberpunk text, the novel Neuromancer (not published until 1984), because Blade Runner was so much the vision he had inside his head. It is perhaps the only case of cinematic science-fiction prefiguring a trend in publishing.

The so-called ‘Blade Runner look’, brimming over with dense, rundown future streets, punked-out populaces and media bombardment has become the single most copied look in science-fiction of the 1980s, 1990s and beyond, while Blade Runner‘s theme of rogue androids, along with The Terminator (1984), inspired a series of B-budget killer android movies.

Blade Runner is a beautifully lit and photographed film. Ridley Scott treats it as film noir, outfitting Deckard in trenchcoat – there was to be the felt hat but Harrison Ford had just done Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) – and Rachel, the femme fatale, in high-padded shoulders and a pall of cigarette smoke, while shooting seedy Chinatown settings and Venetian-blind shrouded bachelor’s apartments. It doesn’t always work – the story is restricted, it never twists and enfolds you the way a good film noir detective story does, rather the film seems more composed as a series of individual scenes. Deckard is not a well fleshed character with Harrison Ford’s performance being a dour one. (The original casting choice was Dustin Hoffman who would have been much better). We never get any particular insight into the way that Deckard is having his humanity challenged by the replicants – ironically, all of the life in the film belongs to the replicants themselves.

The most exciting character is Roy Batty – Ridley Scott chose the then unknown Dutch actor Rutger Hauer for his Teutonic, non-identifiably American looks. (Indeed, Hauer’s Batty could be the perfect incarnation of pulp hero Doc Savage). Scott dresses him in leathers, lighting him from beneath and Hauer dominates every scene he strides through with an electric presence that is at turns frightening, childishly playful and innocent. The climactic confrontation is a marvellous piece – “That’s the spirit,” he laughs as Harrison Ford bashes his head with a lead pipe. Rutger Hauer has gone onto a series of other action roles since Blade Runner but has never done anything as exciting and charged as this.

Where Blade Runner has fault is in the horrendous ending that was tacked on in the original theatrical release. There would have been a great ending as it is where Deckard returns to his apartment to find Goff leaving, who sneers in passing “I hope she’s worth it. She won’t live. But then again, who does?” The tacked-on happy ending has Deckard and Rachel flying across the first green countryside we have seen in the film where Harrison Ford’s grating Marlowe-esque voice-over explains that Rachel did not have a built-in lifespan after all and that she and Deckard can live happily ever after. It is thought that this was tacked on by the studio but Ridley Scott says he chose it himself, seeing the film in need of something more upbeat. If so, his judgment is seriously in error – it is so grossly unreal and forced an ending that it produces groans of disbelief.

Perhaps Scott was right though – Blade Runner was not a huge success in its time and was considered a financial failure. (Its cult reputation only grew subsequent to that). However, the 1992 laser disc and cinema re-release known as Blade Runner – The Director’s Cut restores much of Ridley Scott’s vision, eliminating the voice-overs, the ‘happy’ ending and restoring an integral sequence – the unicorn dream – that offers the suggestion that Deckard may be a replicant. In 2007, Scott also released Blade Runner: The Final Cut, which substitutes minor shots and digitally retouches some of the effects and visible wires and is intended to be considered the most complete version of the film.

There have been occasional talks of a Blade Runner sequel. This finally emerged as Blade Runner 2049 (2017) directed by Denis Villeneuve. Blade Runner: Black Lotus (2021-2) was a Japanese anime tv series spinoff that lasted for thirteen episodes.

Ridley Scott later returned to genre filmmaking with the adult fairy-tale Legend (1985), Hannibal (2001), the Alien prequels Prometheus (2012) and Alien: Covenant (2017), and The Martian (2015) about an astronaut stranded on Mars. He has gone on to make a large number of other non-genre films, including Someone to Watch Over Me (1987), Black Rain (1989), 1492: Conquest of Paradise (1992), White Squall (1996), G.I. Jane (1997), the Oscar-winning Gladiator (2000), Black Hawk Down (2001), Matchstick Men (2003), Kingdom of Heaven (2005), A Good Year (2006), American Gangster (2007), Body of Lies (2008), Robin Hood (2010), The Counselor (2013), Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014), All the Money in the World (2017), House of Gucci (2021), The Last Duel (2021) and Napoleon (2023). Scott has also produced other genre works such as the erotic horror anthology series The Hunger (1997), the psycho black comedy Clay Pigeons (1998), the historic Tristan + Isolde (2006), the tv mini-series remake of The Andromeda Strain (2008), the transplant horror Tell-Tale (2009), the tv mini-series remake of Coma (2012), the tv mini-series Labyrinth (2012) about the quest for the Holy Grail, the horror film Stoker (2013), the videogame-adapted web-series Halo Nightfall (2014), Child 44 (2015) about the hunt for a serial killer in Stalinist Russia, the dystopian sf film Equals (2015), the tv series adaptation of The Man in the High Castle (2015-9), the artificial intelligence film Morgan (2016), Blade Runner 2049 (2017), the Found Footage UFO film Phoenix Forgotten (2017), the true-life-based tv series Strange Angel (2018-9) about pioneering rocketry and occultism, the Arctic horror tv mini-series The Terror (2018-9), the android film Zoe (2018), the BBC mini-series version of A Christmas Carol (2019), the planetary colonisation tv series Raised By Wolves (2020-2) and the true crime film Boston Strangler (2023).

Screenwriter David Peoples would go on to write a number of other genre works including Leviathan (1989), Twelve Monkeys (1995) and Soldier (1998), as well as directing the interesting post-holocaust sports film The Salute of the Jugger/The Blood of Heroes (1990) and winning an Oscar for writing the stunningly nihilistic Clint Eastwood Western Unforgiven (1992). Hampton Fancher was largely assumed to be a Writer’s Guild arbitration credit until Fancher proved his mettle with the intelligent and underrated serial killer thriller The Minus Man (1999).

Other Philip K. Dick adaptations are Total Recall (1990), Screamers (1995), Impostor (2002), Minority Report (2002), Paycheck (2003), A Scanner Darkly (2006), Next (2007), The Adjustment Bureau (2011), Total Recall (2012), Radio Free Albemuth (2014), the tv series adaptation of The Man in the High Castle (2015-9) and the tv anthology series Philip K. Dick’s Electric Dreams (2017-8). The Gospel According to Philip K. Dick (2000) is a fascinating documentary about Dick’s bizarre life.

Trailer here