Israel/France/Belgium/Germany/Poland/Luxembourg. 2013.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Ari Folman, Based on the Novel The Futurological Congress (1971) by Stanislaw Lem, Producers – Reingard Brundig, Sebastien Delloye, Piotr Dzieciol, Ari Folman, David Grumbach, Eitan Manzuri, Ewa Puszczynska & Robin Wright, Photography – Michal Englert, Music – Max Richter, Visual Effects Supervisor – Nitzan Roiy, Special Effects Supervisor – Michael Lantieri, Production Design – David Polonsky. Production Company – Brigit Folman Film Gang/Pandora Filmproduktion.

Cast

Robin Wright (Herself), Harvey Keitel (Al), Danny Huston (Jeff Green), Kodi Smit-McPhee (Aaron Barker), Paul Giamatti (Dr Barker), Jon Hamm (Voice of Dylan Truliner), Sami Gayle (Sarah Wright), Michael Stahl-David (Steve)

Plot

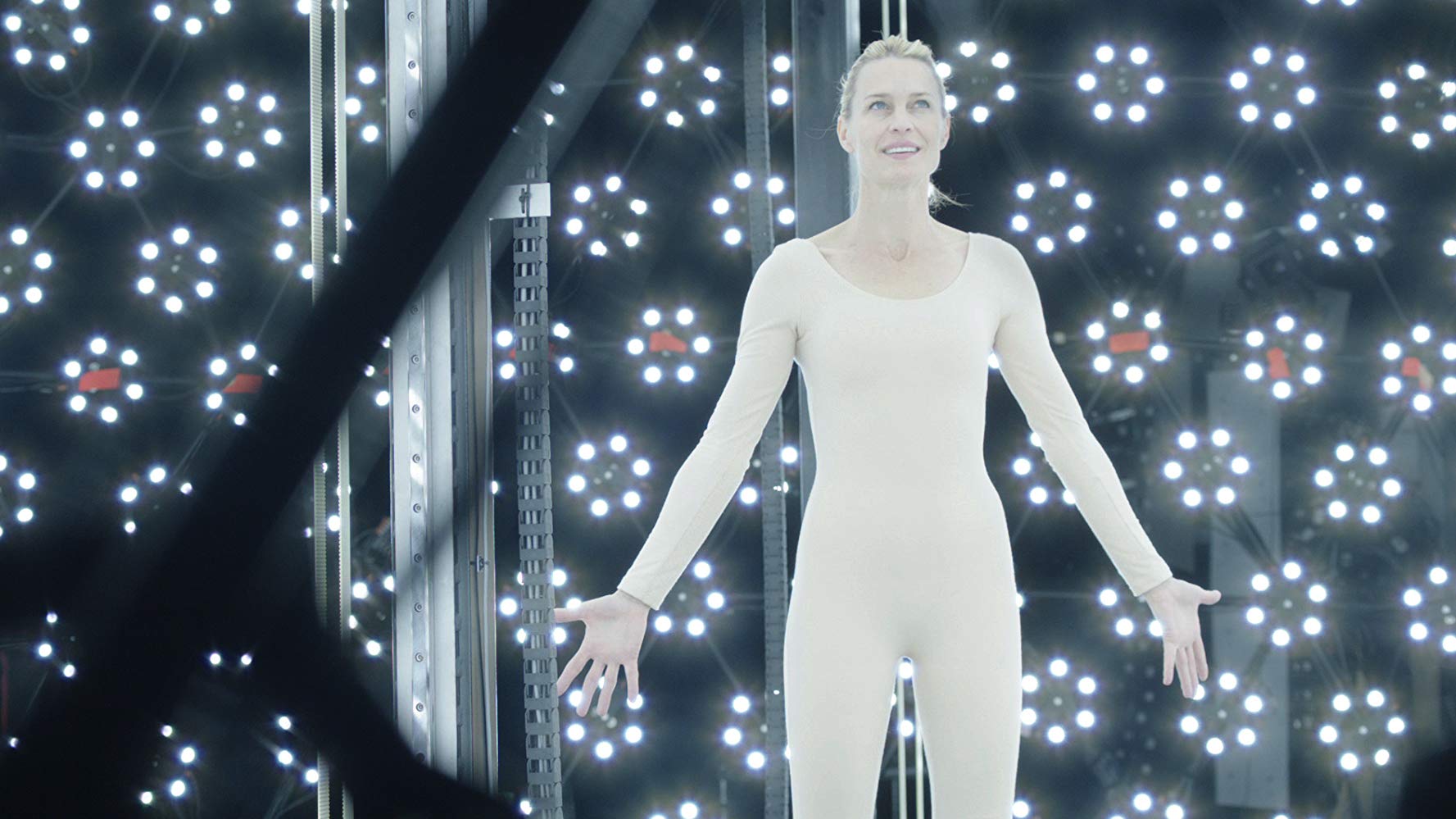

The actress Robin Wright is approached by her agent Al with an offer from Miramount Studios. They want to model her body and expressions to create a virtual version of her, an actress that can be placed into any role at any age. Robin has misgivings about this but eventually allows herself to be scanned. Twenty years later, Robin, now in her sixties, has become a big-name actress in her virtual roles. She attends the Futurist Congress being held inside the Animated Zone. Here all the attendees take a drug that allows them to appear as animated avatars. She is to introduce Miramount’s new product line, however the congress is overrun by terrorists. Miramount executives flee with Robin but the helicopter crashes. It is decided she should be placed in frozen suspension for several years until medical technology can catch up and heal her. She is brought around in a world where everybody lives inside a Utopian illusion where they can adopt any form or identity they want. Through this bewildering and unrecognisable world, Robin seeks to reconnect with her son.

Ari Folman is an Israeli director who first emerged as co-director of Saint Clara (1996), a film about a clairvoyant young girl, which gained some international festival play. He then made Made in Israel (2001) about which I can’t find any information, although the IMDB states that it has a near-future setting. The film that made Folman’s name however was Waltz With Bashir (2008), an innovative psychotherapeutic autobiography analysing his own experiences in conflict while serving in the Israeli army, which was all presented in animation. The film gained considerable international attention, including being nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Folman subsequently went on to make the animated Where is Anne Frank (2021) where Anne Frank’s imaginary companion comes to life in the present-day.

Stanislaw Lem (1921-2006) was a Polish science-fiction writer. Emerging during the height of the Communist rule of Poland, Lem began publishing with The Astronauts (1951) and produced a number of other classic works such as Memoirs Found in a Bathtub (1961), Solaris (1961), The Cyberiad (1965), The Futurological Congress (1971) and The Star Diaries (1976), among many others. Lem managed to conduct some challenging ideas, despite his work being published under the eye of Communist censorship. Films based on his works include First Spaceship on Venus (1959), Ikarie XB-1/Voyage to the End of the Universe (1963), Solaris (1972), Test Pilot Pirx (1979), Solaris (2002), 1 (2009) and His Master’s Voice (2018).

The Congress is loosely based on Stanislaw Lem’s The Futurological Congress. The book was a black comedy in the trippy Philip K. Dick vein wherein the protagonist attends the title conference and accidentally imbibes some hallucinogens to find himself in a surreal future world where everybody takes drugs that allow them to live in a consensual illusion where they can adopt whatever appearance they want. In the film, Ari Folman has shoehorned this onto another plot altogether about Robin Wright (playing herself) and the issues surrounding her being cast as a virtual actress, no equivalent of which exists in the book. (A straight version of the book would only comprise the second and third sections of the film).

During these scenes, Folman makes a number of satiric digs at the Hollywood system – a studio run by Miramount (an obnoxiously funny Danny Huston), clearly an amalgam of Paramount and Miramax – and celebrity obsessed culture, which are not there in the book. Lem was also writing well before the advent of the internet or Virtual Reality and, although Folman keeps to his idea of an hallucinogenic drug, the book makes far more relevance in terms of internet culture and avatar bodies.

I felt annoyed with The Congress during its first act, which is centred around Robin Wright being persuaded to become a virtual actress. Here the film seems to be channelling other works on the subject such as Looker (1981) and S1m0ne (2002). I couldn’t get into the film as I kept finding the fundamental set-up implausible – the idea that people would allow their image to be scanned and that they would subsequently lose control over what was done with their form. The film introduces a lawyer character but the most obvious thing that would almost certainly arise never comes into play – that actors would demand copyright on their own image and would license it for each individual role in much the same way that musicians and writers get royalties from reissues and samplings, which would invalidate almost all of the issues that people seem to be getting worked up about.

There are some pluses during this sections. Danny Huston gives an amusingly caustic performance as a Hollywood exec, at one point blasting The Lord of the Rings as making a more interesting movie than a book. Robin Wright also gets a good many not entirely flattering digs made in the direction of the downward spiral of her career and casting choices made since The Princess Bride (1987). Harvey Keitel’s presence is largely superfluous but he does shine in one fine scene where he tells Robin Wright the story of how he became an agent, in so doing taking her through the range of emotions that the scanning technician wants her to play out.

The second section set twenty years later abruptly heads for WTF territory and makes a bewildering comparison to the previous section. We meet an older version of Robin Wright as she attends the congress in the Animated Zone. Here Ari Folman abandons live-action and realism and heads off into absurdism as the animated Robin Wright drives through a landscape peopled by giant octopuses, airplanes that fly by flapping their wings and caricatures of celebrities. The world is a constant marvel (even if the quality of animation is somewhat limited). Here the film seems to dive off into a stylised look that seems akin to The Ren & Stimpy Show (1991-6) or Aachi & Ssipak (2006).

I spent most of this section trying to work out what was going on – was this world some type of drug-induced consensual mass hallucination with everybody inhabiting avatar bodies akin to Virtual Reality? You get this impression but contradicting this, we meet characters like Dylan Truliner who introduces himself as Robin’s animator and get a peek in on a team of animators feverishly working away and you wonder if this a world where people somehow physically becomes toons akin to Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988).

The final section is set during the utopia sometime in the future where the absurdist animation goes into overdrive. Everyone lives in a bewilderingly surreal world filled with extravagant costuming and buildings, over-ornamented appearances and appropriated celebrity lookalikes. People casually fly and flora blooms everywhere, even overruns the bodies of Robin and Dylan as they make love. The film reaches its most potent point when [PLOT SPOILERS] Robin Wright elects to take the pill that allows her to exit the illusion and finds a grimy, bedraggled (live-action) world where the populace lives in ruins. This punctures the wild surrealism that we have seen for the better part of the previous hour with undeniable effect. The ending the film comes to is a peculiarly touching one.

Stanislaw Lem was one of the great science-fiction satirists, up there in the company of writers like Kurt Vonnegut Jr, Douglas Adams and John Sladek. The book version of The Futurological Congress comes filled with a series of hilariously deadpan science-fiction gags and in particular contrasts between reality and illusion during the latter scenes when the protagonist exits into the real world.

By contrast, Ari Folman treats his film more seriously. His satire is reserved for Hollywood and celebrity, mostly in the first section. This tends to turn the latter sections into an artificial reality/conceptual breakthrough film akin to a spate of ones that we had a few years ago with the likes of Total Recall (1990), Open Your Eyes (1997), Dark City (1998), The Matrix (1999) and Avalon (2001), which makes it slightly the lesser than Lem’s hilarious work. Certainly, Lem’s idea of the populace of the future living inside an illusion has had its edge taken off it somewhat by The Matrix. Still, you have to applaud the conceptual reach that Ari Folman grasps for and largely ends up pulling off.

Trailer here