USA. 1955.

Crew

Director – Byron Haskin, Screenplay – James O’Hanlon, Adaptation – Barré Lyndon, George Worthing Yates & Philip Yordan, Based on the Book by Chesley Bonestell & Willy Ley, Producer – George Pal, Photography – Lionel Lindon, Music – Van Cleave, Photographic Effects – Ivyl Burks, Jan Domela, John P. Fulton, Paul Lerpae & Irwin Roberts, Process Photography – Farciot Edouard, Makeup Supervisor – Wally Westmore, Art Direction – Joseph MacMillan Johnson & Hal Pereira, Astronomical Art – Chesley Bonsetell. Production Company – Paramount.

Cast

Walter Brooke (Colonel/General Samuel Merritt), Eric Fleming (Captain Barney Merritt), Phil Foster (Sergeant Jackie Siegle), Mickey Shaughnessy (Sergeant Mahoney), Benson Fong (Sergeant Imoto), Ross Martin (Sergeant Andrei Fodor)

Plot

On the orbiting space station The Wheel, construction is underway on a rocketship for the first manned Moon landing. However, the men aboard The Wheel are experiencing stress after a year in space and the commanding officer Colonel Merritt’s harsh refusal to allow any leave. Orders then come to change the rocket’s intended destination from the Moon to Mars. The rocket is launched. Once underway, Merritt becomes increasingly preoccupied with religious fixations and the belief that the mission is contravening God’s will. This culminates in his causing the rocket to crash, stranding the crew on Mars.

Producer George Pal came to considerable attention with Destination Moon (1950). Destination Moon was the one of boldest science-fiction films made up until that time, coming not only with an extraordinary optimism and zealous invocation about mankind’s capacity to conquer new frontiers but also with plausibly detailed engineering schematics for how to do so. Single-handedly it inspired the great wave of 1950s science-fiction films. Amongst these, George Pal became the most pre-eminent producer – indeed, the only producer of the era to be regularly making science-fiction on an A-budget – going onto make other genre classics of the era such as When Worlds Collide (1951), The War of the Worlds (1953), The Naked Jungle (1954) and The Time Machine (1960). (See below for George Pal’s other films).

Conquest of Space was a sequel of sorts to Destination Moon on Pal’s part. It isn’t a sequel in any direct sense, more in a thematic sense. You can see the thinking that went on – the very title suggests an escalation of scale beyond the Moon to taking on the whole of space. (The title was taken from a 1949 work of non-fictional speculations about the form of future space travel by rocket engineer Willy Ley and astronomical artist Chesley Bonestell. Bonestell had also designed the Moon sets for Destination Moon). In many respects, one can see Conquest of Space setting out to expand and improve upon Destination Moon.

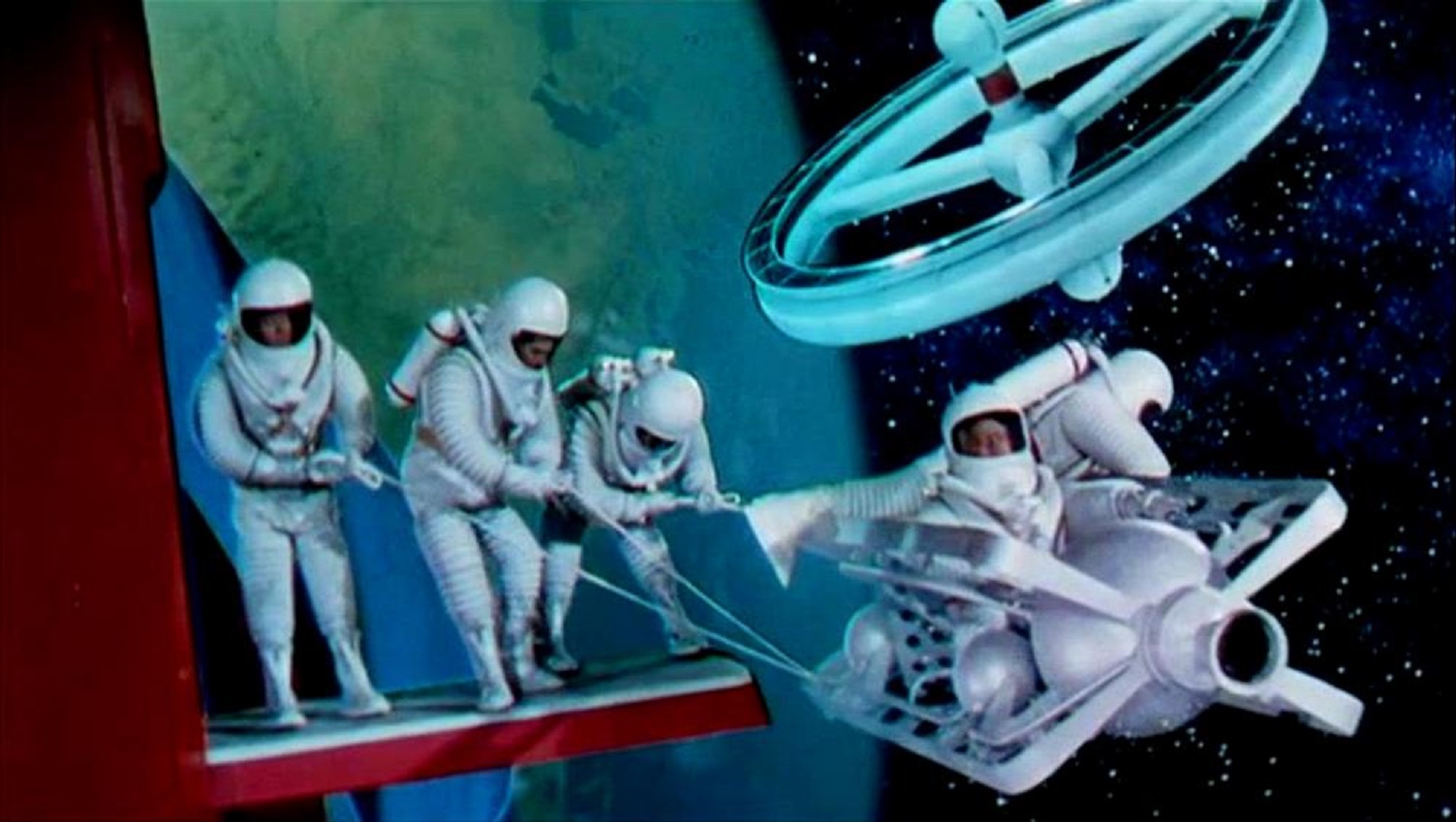

George Pal has clearly taken to heart the criticisms made that the characters in Destination Moon were faceless – unfortunately the attempts at characterization here overcompensate by indulging in a lowbrow comedy relief that turns the astronauts into something akin to the simple-minded comic-relief GI’s out of a WWII movie. The film also offers up a multi-racial complement of astronauts, although the attempts at ethnic diversity end up trading up on hopelessly racist caricatures. (There is a bizarre scene where a Japanese astronaut argues for the need to go to Mars and find new minerals on the grounds that if the Japanese had had metals with which to build houses and cutlery they would never have had to declare war on the US in 1941). Nevertheless, Conquest of Space does have some odd moments of engaging humour that Destination Moon never had – like the scenes around the dinnertable with the astronauts passing processed food pills – “coffee … milk … sugar … corn beef, please.”

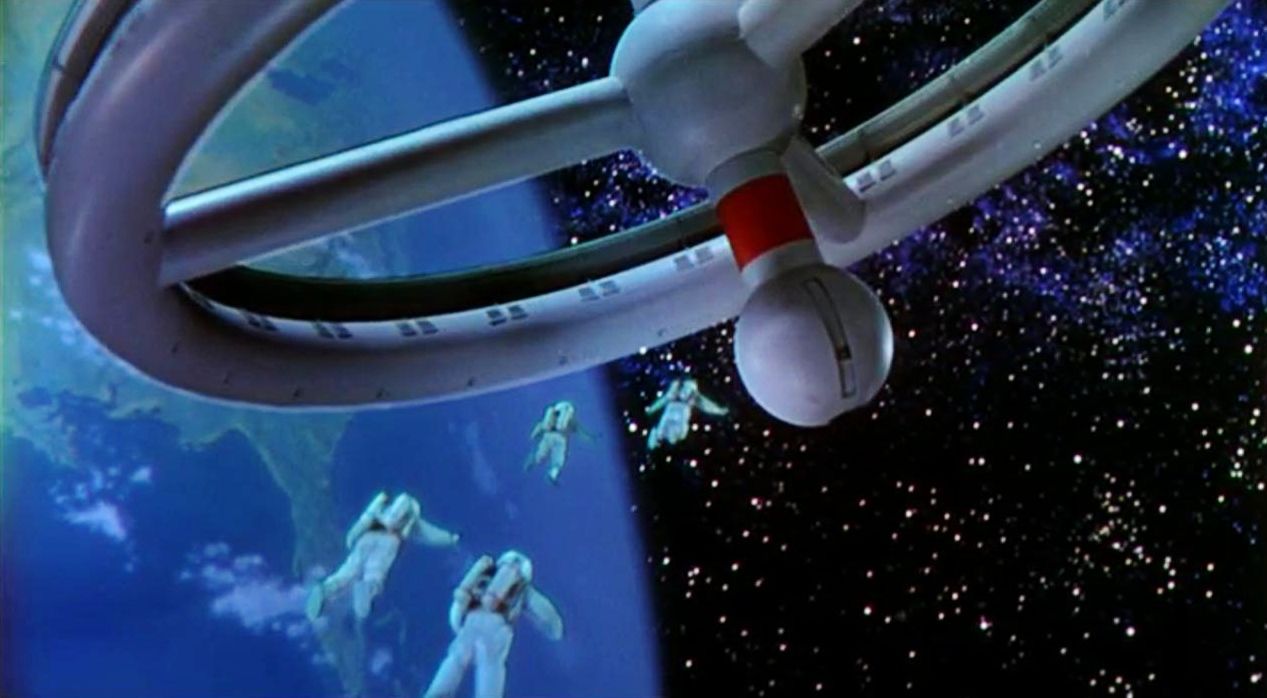

The effects in the film are generally up to the high quality associated with George Pal, although are often variable. There are some decent shots of The Wheel orbiting the Earth and the space taxi docking. There is a grandness of imagery (considerably boosted by Van Cleave’s musical score) in the shots of the rocket departing the Earth or attempting to outrace an oncoming asteroid. One scene with a dead astronaut being ‘buried’ in space by being fired on a trajectory into the sun even manages to touch the affectingly poignant. However, other effects shots come with thick matte lines and one sequence with The Wheel being hit by a meteorite storm embarrassingly reveals the Wheel as only being a model bounced about on visible wires.

With Chesley Bonestell on board as scientific adviser one would have thought that some of the science would have come out more accurately – the Mars rocket is unconnected to the rotating Wheel, which would cause considerable problems in docking and a wastage of energy each time the men went to work, whereas having the rocket tethered to The Wheel’s rotational axis would be much more efficient. And the whole concept of building a space station in order to then build a rocket for a Moon shot is inefficient engineering – as the real space programme revealed, there would be far greater ease in building a single rocket for a Moon shot that making multiple flights into orbit for the construction of a space station.

What does Conquest of Space in however is its bizarre religious undertow. The film works not too badly during the first half and in the launching of the rocket but seems to go completely off the deep end after that. Once the mission is underway, the commander begins to rant: “We can still reach the destination as planned, which may be Heaven or Hell. This voyage is an abomination. If it were possible I would come back now, return with this ship and blow it up along with plans for building another.” This is all the more bizarre for being a character twist that comes completely out of the blue. Where Destination Moon conducted an extraordinarily bold and unfettered leap of imagination forth into unconquered frontiers, it is almost as though Conquest of Space has submitted to the anxiety that permeated every other 1950s science fiction film since Destination Moon. You are never entirely sure if this variant on the hoary old “there are things mankind was not meant to know” is one that the film believes or is merely using as a melodramatic plot device – the whole twist is so left field it is impossible to tell.

Most of George Pal’s films had a strong religious undertow – Pal himself was a Catholic. In The War of the Worlds, the ironic ending of the atheist H.G. Wells’s novel where the Martians were destroyed by the “smallest thing on God’s Earth” was transformed into a full-blown religious passover with humanity praising the Almighty for their deliverance; while When Worlds Collide played the film’s Noah’s Ark allegory up for all it possibly could. Conquest of Space ends on a note of cautious optimism by again resorting to religion – the astronauts are stranded on Mars but on Christmas Day it begins to snow (amid ringing bells on the soundtrack) and plant life begins to sprout – “only God can make trees” one character notes – which provides the astronauts with their unexpected salvation.

It is an extraordinary comedown from the enormous optimism of Destination Moon – where Destination Moon seemed filled with unbound, unlimited certainty about Man’s ability to conquer space, Conquest of Space seems to hover uncertainly between whether mankind will conquer new frontiers or is treading into territories that defy divine provenance. Destination Moon‘s end comes with the astronauts saving the mission through their own ingenuity, whereas Conquest of Space‘s astronauts’ ingenuity runs into a brick wall and their salvation comes only by The Almighty deciding to cast His favour upon them. It is a move from humankind as bold conqueror of the new frontier to humanity as humbled churchgoer.

Ultimately, Conquest of Space is a curiously failed film. Where it does work it works by doing what George Pal does best – showing grand-scale special effects scenes – and by repeating all the things that made Destination Moon work – in depicting the alienness of the worlds of the Solar System and portraying a scientifically credible space mission. And where it fails to work is equally in places where George Pal’s films were always at their weakest – wooden characters and a woolly-headed religiousness that showed through not far beneath the surface.

George Pal’s other genre films Destination Moon (1950), When Worlds Collide (1951), The War of the Worlds (1953), The Naked Jungle (1954), tom thumb (1958), The Time Machine (1960), Atlantis, the Lost Continent (1961), The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962), 7 Faces of Dr Lao (1964), The Power (1968) and Doc Savage – The Man of Bronze (1975).

Byron Haskin worked with George Pal on several other occasions including The War of the Worlds, The Naked Jungle and The Power. Haskin also directed a number of other genre films including Tarzan’s Peril (1951), From the Earth to the Moon (1958), Captain Sindbad (1963) and Robinson Crusoe on Mars (1964), as well as episodes of the classic science-fiction anthology series The Outer Limits (1963-5).

Trailer here