Crew

Director/Screenplay – David Cronenberg, Based on the Novel Cosmopolis by Don DeLillo, Producers – Paulo Branco & Martin Katz, Photography – Peter Suschitzky, Music – Howard Shore, Visual Effects – Mr X Inc (Supervisor – Wojciech Zielinski), Special Effects Supervisor – Warren Appleby, Makeup Design – Stephen Dupuis, Production Design – Arvinder Grewal. Production Company – Alfama Films/Prospero Pictures/Kinologic Films (DC)/France 2 Cinema/Telefilm Canada/Talandracas Pictures/France Televisions/Canal Plus/Rai Cinema/RTP/Ontario Media Development Corp/Astral Media the Harold Greenberg Fund/Jouror Prods/Leopardo Filmes.

Cast

Robert Pattinson (Eric Packer), Paul Giamatti (Benno Levin), Sarah Gadon (Elise Shifrin), Kevin Durand (Torval), Samantha Morton (Vija Kinsky), Juliette Binoche (Didi Fancher), Jay Baruchel (Shiner), Emily Hampshire (Jane Melman), Mathieu Amalric (Andre Petrescu), Patricia McKenzie (Kendra Hays), Philip Nozuka (Michael Chin)

Plot

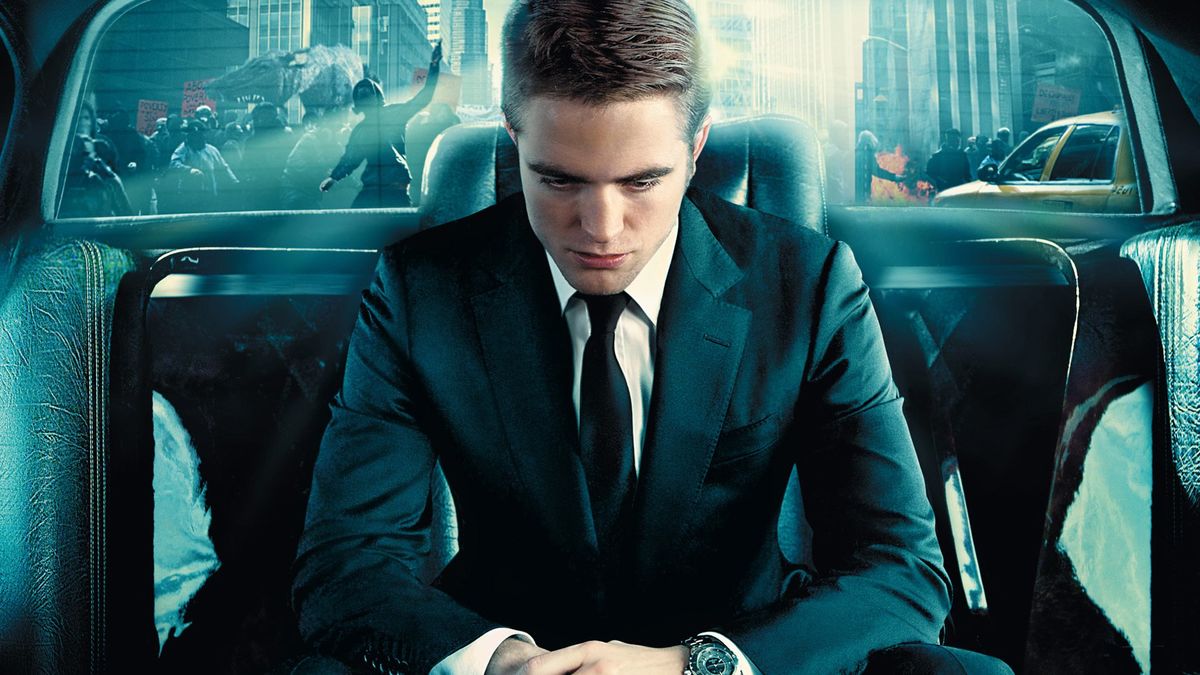

Eric Packer, a manager of financial assets who is worth billions, decides he wants to travel across Manhattan for a haircut. His chief of security warns him that the journey will be slow and difficult due to the fact that the streets are being held up by a Presidential parade and protestors. Packer is determined and they set out in his stretch limousine. Along the way, various people stop by to talk with, advise and have sex with Eric. He makes attempts to connect with his wife Elise who appears to be aloof. The yuan is falling badly and Eric is losing billions but he feels strangely enlivened by this. As events in the street become more chaotic, Eric’s security detail learns that there is a credible threat against his life.

Canada’s David Cronenberg is one of the cultiest of genre directors. Cronenberg began making arty experimental films such as Stereo (1969) and Crimes of the Future (1970), before gaining success with a series of vivid B movies – Shivers/They Came from Within (1975), Rabid (1976) and The Brood (1979). Cronenberg’s work became increasingly more successful, mainstream and better budgeted with the likes of Scanners (1981), Videodrome (1983), The Dead Zone (1983) and The Fly (1986). After Dead Ringers (1988), his greatest masterpiece, a disturbingly clinical venture into the troubled relationship between twins, Cronenberg began to venture away from any easy pigeonholing as a genre director. His successive works throughout the 1990s included challenging literary adaptations and ventures into alternate sexuality such as Naked Lunch (1991), M. Butterfly (1993) and Crash (1996), a surprisingly dull Virtual Reality film with eXistenZ (1999) and a subjective portrait of mental illness in Spider (2002). Cronenberg’s works of the 00s have left any association with genre material and/or disturbed psychology and simply been straight dramas with the likes of A History of Violence (2005), Eastern Promises (2007), A Dangerous Method (2011) and Maps to the Stars (2014), before an extraordinary return to genre material with Crimes of the Future (2022).

With Cosmopolis, Cronenberg has adapted a book by American novelist and playwright Don DeLillo. DeLillo is in his seventies and has been publishing since 1971, producing works such as White Noise (1985), Libra (1988), a fictional treatment of the life of Lee Harvey Oswald, Underworld (1997), The Body Artist (2001), Falling Man (2007) and Point Omega (2007). Don DeLillo’s books are works of social criticism that tackle many of the ideas of the postmodern identity crisis. He has won numerous awards, although he has been known to readily absorb science-fictional themes into his works. The only previous DeLillo work to be filmed was his screenplay for the baseball film Game 6 (2005) and Noah Baumbach’s subsequent adaptation of White Noise (2022). Cosmopolis (2003) was originally written about the collapse of the dotcom bubble in 2001 but Cronenberg has smartly updated it as a work about the 2008 recession and Occupy era. Cronenberg remains surprisingly faithful to the book, frequently using DeLillo’s dialogue exactly as it is.

You search for comparisons to describe Cosmopolis. It is vaguely, impliedly science-fictional. The publicity machine states that the setting is near-future; some of the technology is futuristic – voice-coded handguns and the hi-tech limo interior; while there is the sense of macrocosmic social collapse going on outside the windows of Robert Pattinson’s limousine. You could compare Cosmopolis to a film like Strange Days (1995), which had a similar sense of drifting through a world on the verge of social collapse and was told from the point-of-view of a limo driver. Or perhaps some of William Gibson’s more recent novels – Pattern Recognition (2003), Spook Country (2007) and Zero History (2010) – that treat the contemporary world in terms of being works of science-fiction.

In tone, the film’s surreal drift through an economically collapsing world, consisting of vignettes involving characters who step into Robert Pattinson’s limousine and life – everything from tech, art and financial critics come to give/seek advice, doctors giving Pattinson rectal exams, anarchists come to cream pie him as an artistic statement – the film resembles the works of Luis Buñuel. There is something akin to the surreal tableaux of Buñuel The Phantom of Liberty (1974), while Robert Pattinson’s determination to get a haircut (which he never fully does) reminds of the party constantly trying to go to dinner in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972).

If you want the soundbite comparison, you could compare Cosmopolis to a conceptual collision between Wall Street (1987) and Fight Club (1999). From Wall Street, we get a work that is determined to head-on confront the moral issues of capitalism. Like Fight Club, it is a work that attempts to philosophically tackle the contemporary world. Both films write dialogue in terms of agitprop sloganeering – cryptic phrases here like “money has lost its narrative quality”, “time is a corporate asset” – that you could easily see as ending up on a T-shirt or as a piece of graffiti. I am of the firm belief that Cosmopolis is a cult film that is waiting to find its audience. On the other hand, it makes for a far more difficult sell as a cult film than Fight Club did. Where Fight Club existed as a manifesto for reclamation of identity by men who felt disenfranchised by the modern world, Cosmopolis sits at the cool distance of a ride in a mirrored and sound-proofed limousine, looking on at the spectacle of a collapsing world. It is detached rather than up in arms, even if both films chart the eventual self-destruction of their protagonist and the symbolic collapse of capitalism.

I enjoyed Cosmopolis enormously. The David Cronenberg who abandoned making horror films in the early 1990s has not always been an easy one, even if it is the Cronenberg who has been greeted as a serious director and whose works have garnered awards attention. I far preferred the earlier Cronenberg who made B-horror movies shot through with amazing metaphors and perverse sexuality. His films from the 1990s onwards have been artistically challenging – adaptations of difficult literary works like Naked Lunch and Crash – and explorations of psychology – Spider, A History of Violence, Eastern Promises, A Dangerous Method – that have felt increasingly mannered and, while by no means bad films, lacking in the fired-up charge of his earlier work. None of the last four films listed travel into territory as disturbing or perverse as Cronenberg’s singular masterpiece Dead Ringers. Cosmopolis is the first of David Cronenberg’s films in the better part of the last decade-and-a-half that feels like it fires up with a brilliance and bite. It is the best work he has delivered since Dead Ringers.

Part of the brilliance of Cosmopolis is that Cronenberg remains almost entirely faithful to Don DeLillo’s characters and dialogue, often transposing sections of dialogue direct from the book. This makes for a film that comes with a heady swim of trenchant aphorisms and oblique observations on the state of the world and/or economics – it is a film that you immediately want to return and watch again just to absorb more of the dialogue.

Cronenberg directs in the peculiarly detached way he has – something best seen in Crash where he gives us a film of people having sex that it is made to feel like actions performed by blankly disconnected bodies, or the scenes in eXistenZ where the characters are taken over to perform roles in the virtual simulation. The dialogue often feels like something being performed by robots on a blank stage. There is a particularly hilarious scene where Robert Pattinson tries to connect with his wife (Sarah Gadon), which ends with the two of them resigning themselves to the fact that the marriage is over in a way that involves almost no feeling passed during the exchange.

Cronenberg often has a very subtly couched sense of black humour in his films – the blankness of the dialogue here makes this seem even more so. There is an hilarious scene where Robert Pattinson asks bodyguard Kevin Durand about his hi-tech handgun with its keypad and voice-controlled password and unlocks it, only to promptly shoot Durand with it and then proceed on as though nothing has happened. Much of the film follows Pattinson’s progression through a society on the brink of social collapse and how his own impending financial ruin becomes something liberating to him. It eventually becomes about Pattinson trying to find some way to feel things again – the rather funny scenes where he asks bodyguard Patricia McKenzie to zap him with a taser so he can feel what it is like, or where he shoots himself through the hand with Paul Giamatti’s gun to see what happens and then seems surprised that it hurts.

The film has an impressive cast line-up, most of whom only make single scene cameos. Juliette Binoche, for example, gets second billing even though she has a brief scene at the start that is shorter than many by the other name actors. The one who emerges the best out of this is surprisingly Robert Pattinson who delivers a performance of coolly reptilian aloofness. I was impressed with Pattinson when he first hit superstardom in Twilight (2008). The subsequent Twilight sequels seem happy to shuffle him around in a series of shirtless poses where Pattinson gives the impression that he is sleepwalking his way through a role that is being stage-managed on his behalf by the makeup, hair styling and costuming people. Here he has chosen to work with a decidedly non-commercial director like David Cronenberg in a clear desire to take on something challenging in the acting department – it is hard, for example, to imagine any of the predominantly teenage girl audience that the Twilight series is aimed at flocking to Cosmopolis in droves or even understanding what the film is about. One suspects that Pattinson is attempting to do something akin to what Johnny Depp did in the early 1990s, which was to parlay his pin-up success to working with a series of directors doing intelligent, quality material, as opposed to allowing himself to be shuffled around in a series of vapid roles that play solely on his good looks and would doom him to a shelf-life of about five minutes – a trap that Pattinson’s co-star Taylor Lautner has fallen into – and in so doing charted a position for himself as a serious actor.

David Cronenberg’s other films are:– Stereo (1969), a little-seen film about psychic powers experiments; Crimes of the Future (1970) set a future where people have become sterile and developed strange mutations; Shivers/They Came from Within (1975) about sexual fetish inducing parasites; Rabid (1977) about a vampiric skin graft; The Brood (1979) about experimental psycho-therapies; Fast Company (1979), a non-genre film about car racing; Scanners (1981), a film about psychic powers; Videodrome (1983) about reality-manipulating tv; The Dead Zone (1983), his adaptation of the Stephen King novel about precognition; The Fly (1986), his remake of the 1950s film; Dead Ringers (1988) about two disturbed twin gynaecologists; Naked Lunch (1991), his surreal adaptation of William S. Burroughs’ drug-hazed counter-culture novel; M. Butterfly (1993), a non-genre film about a Chinese spy who posed as a woman to seduce a British diplomat; Crash (1996), Cronenberg’s adaptation of J.G. Ballard’s novel about the eroticism of car crashes; eXistenZ (1999), a disappointing film about Virtual Reality; Spider (2002), a subjective film takes place inside the mind of a mentally ill man; the thriller A History of Violence (2005) about an assassin hiding from his past life; Eastern Promises (2007) about the Russian Mafia; A Dangerous Method (2011) about the early years of psychotherapy; the dark Hollywood film Maps to the Stars (2014); Crimes of the Future (2022) set in a future world of surgical performance art; and The Shrouds (2024) about the development of a technology that places videocameras inside graves. Cronenberg has also made acting appearances in other people films including as a serial killer psychologist in Clive Barker’s Nightbreed (1990); a hitman in Gus Van Sant’s To Die For (1995); a Mafia head in Blood & Donuts (1995); a member of a hospital board of governors in the medical thriller Extreme Measures (1996); as a gas company exec in Don McKellar’s excellent end of the world drama Last Night (1998); and a priest in the serial killer thriller Resurrection (1999); and a victim in the Friday the 13th film Jason X (2001).

(Winner for Best Film at this site’s Top 10 Films of 2012 list. Winner for Best Adapted Screenplay, Nominee for Best Director (David Cronenberg), Nominee for Best Supporting Actress (Sarah Gadon) at this site’s Best of 2012 Awards).

Trailer here