USA. 1962.

Crew

Director – Wesley E. Barry, Screenplay – Jay Simms, Producers – Wesley E. Barry & Edward J. Kay, Photography – Hal Mohr, Electronic Harmonics – I.F.M., Makeup – Jack Pierce, Special Eye Effects – Dr Louis M. Zabner, Art Direction – Ted Rich. Production Company – Genie Productions.

Cast

Don Megowan (Kenneth Craigus/The Craigus), Don Doolittle (Dr Raven), Erica Elliott (Maxine Megan), George Milan (Acto), Dudley Manlove (Lagan), Frances McCann (Esme Craigus Miles), David Cross (Pax), Malcolm Smith (Court), Richard Vath (Mark), Reid Hammond (Hart), Alton Tabor (Kelly), Pat Bradley (Dr Moffitt)

Plot

It is several years after a nuclear war and the birth rate of the human race is declining. Humanity has turned to creating robots, which have been given the derogatory name of Clickers, for use as a labour force. As these robots have been built with increasing degrees of human-like sophistication, the anti-robot organization The Order of Flesh and Blood has become more active in its protests. Meanwhile, a Clicker underground has secretly started creating their own more sophisticated robot models, which have now become indistinguishable from humans unless dismantled. Kenneth Craigus, a dedicated member of The Order of Flesh and Blood, bursts into the laboratory of Dr Raven and discovers that one of the Clickers has just killed Dr Raven (to prevent him giving away information about the robot modifications that Raven has conducted). The discovery of the first Clicker to kill a human causes great consternation among the Order. Craigus also discovers that his sister Esme has done the unthinkable and signed up for Rapport – has started having a romantic relationship – with a Clicker. As Craigus finds love with Esme’s friend Maxine, the Clickers have even further revelations in store for the two of them.

The Creation of the Humanoids is a little-known low-budget science-fiction film from the 1960s. Discovered today, it proves to be a highly underrated gem of considerable worth. Indeed, The Creation of the Humanoids is a perfect illustration of how science-fiction should work as a literature of ideas rather than of special effects.

The Creation of the Humanoids masters the science-fiction art of compressed and abstrusely littered information dumps – the sort of thing that Cyberpunk perfected two decades later – of being able to depict the future through incidental background details or casual conversational droppings. The opening scene is a mini-masterpiece of science-fictional mise-en-scene that manages to tell us all we need to know about the background of the future via the confrontation between two Clickers and two members of the Order of Flesh and Blood – the humans pull the Clickers up, demanding to see their assignment cards, making threats of keeping them there until their power runs out, to which the robots weakly protest that they have police-accorded rights, before they are allowed to go to their Temple, only for Don Megowan to tell his companion that he realizes that one of the Clickers has a fake id card. It is a scene where we see the entire strata of the future – that robots are a labour force that are treated as a despised underclass by some factions who have started forming vigilante groups, even though the Clickers have been accorded civil rights, and that the Clickers are now plotting sedition and rebellion. (The parallels to the US Civil Rights conflicts of the 1960s must have been unmistakeable to the audiences of the day). There is even the intriguing suggestion with the mention of The Temple that the robots have created their own religion.

There are some parts of the film that are beautifully written science-fiction. Like the exchange between Don Doolittle’s Dr Raven and the Clicker in his lab where the discussion turns to what will happen to the supplier who has been caught for outfitting the Clickers, where it becomes apparent that the authorities will wipe his memory as punishment:-

“Why don’t they just kill him?” Raven asks. “The effect of personal cessation is the same in either case. They just leave a hollow shell walking around.”

“He can still perform his duties.”

“But he is without his past, without hope. A dream gone.”

“Almost like being a robot isn’t it?”

“No offence.”

“I am incapable of taking offence. But why is it that the more we become like men the more they hate us for it?”

In a particularly haunting speech, the Clicker argues with Dr Raven about the robots having a religion: “I know who created me – Hollister Evans and the R47. You have to accept your creator on faith.” There is an incredible literacy of ideas at play here – one that gives us piercing portraits of a future, while asking penetrating philosophical questions about the scenario we are plunged into. This is superb science-fiction writing. There are also a number of similarities, at least during the first half, between The Creation of the Humanoids and Karel Capek’s classic play R.U.R. (1921), which it should be noted introduced the term ‘robot’ to the world.

The latter half of the film throws in some fascinating twists. Like when zealous anti-robot crusader Don Megowan discovers the ultimate humiliation – that his sister (Frances McCann) has taken up in a relationship with a Clicker (David Cross). She passionately argues in favour of how her Clicker is the perfect partner and angrily taunts Megowan: “He’s more man than you’ll ever be.” There are some eerily paranoid moments during their discussion on machine-assisted politics where Esme’s Clicker makes Don Megowan question how much humanity relies on machines by asking him how humanity, in trusting the machines to collate the votes and choose their political leaders, cannot be sure that the machines are not adding supplementary data of their own into the mix.

Of course, there is the classic twist ending [PLOT SPOILERS] – where the lead character is revealed to have been an android all-along without their having known it. This is an ending that was largely invented by writer Philip K. Dick. However, The Creation of the Humanoids was the first film to do this before the android identity bender became a cliche following Dick-inspired films such as Blade Runner (1982), Screamers (1995) and Impostor (2002) and other works like Scream and Scream Again (1970), The Stepford Wives (1975) and tv’s Battlestar Galactica (2003-9). The scene has a marvellous piece of reasoning where it is argued that androids must have souls – if a man can still retain his soul after having limbs removed, then a person who has been resurrected into an artificial body and retains the memory of having faith in a soul surely must have a soul in much the same way as the person missing their limbs still does despite no longer having a whole body. And then there is the suggestion of how the Clickers will be made completely human with the implantation of the last remaining part – reproductive systems.

Moreover, The Creation of the Humanoids takes the idea of the hero discovering he is an android far further than Philip K. Dick ever did. Usually in these Dick-ian twist endings, the idea that one has been replaced by a machine comes as a moment of horror. Here not only does the hero discover that he is an android but the film then turns this around to argue that being an android is far superior to the human condition. It is a remarkable ending. There is a wonderful little final touch where Don Doolittle turns to the camera and addresses it direct: “Of course the operation was a success or you [the audience] wouldn’t be here.”

One of the things that one notices about The Creation of the Humanoids is how it is minimalist science-fiction. The future is depicted via nothing more than a series of plain sets using coloured pastel lighting and simple backdrops of geometric shapes that are used to suggest either sculptings or futuristic architecture. Dramatically, the film is slow. It is almost like an old-fashioned drawing room stage play – all the drama comes through characters talking things out. There is perhaps the tendency to talk the subject to its end – not that any of this proves at all uninteresting.

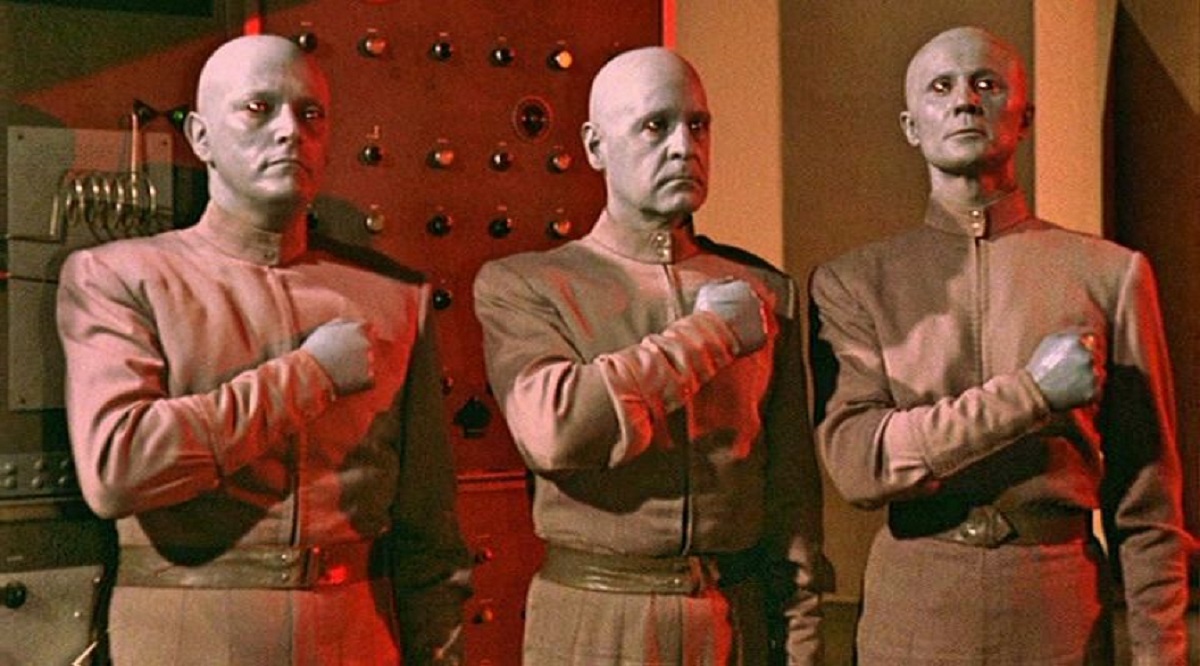

The Clickers are made to look authentically humanoid-looking but blank, outfitted in boiler suits, with bald heads, green greasepaint and unnervingly blank glittering eyes. There is that great moment where one of them announces their plans to become more human-like (all in his blankly dispassionate way): “He will learn how to laugh, how to cry, be afraid, how to hate. To become an R96 is a real sacrifice.” The lack of emotional inflection in such a speech quite gives it something. Among one of the interesting ideas that The Creation of the Humanoids predicts is the idea of the microprocessor with the opening introduction talking about the idea of the Magnetic Integrator Neuron Duplicator (M.I.N.D.), which we are told is “one-hundredth the size of a golf ball.” The score is composed of the ethereal early electronic music as patented by Forbidden Planet (1956), which the film calls ‘electronic harmonics’.

Director Wesley E. Barry, a former actor in bit parts during the 1920s and 30s, elsewhere only ever directed a handful of B Westerns of no note. However, screenwriter Jay Simms wrote a number of other science-fiction films including The Giant Gila Monster (1959), The Killer Shrews (1959), Panic in Year Zero! (1962) and The Resurrection of Zachary Wheeler (1971).

Buy this film from Dark Sky Films

Trailer here