USA. 1950.

Crew

Director – Irving Pichel, Screenplay – Robert A. Heinlein, James O’Hanlon & Rip Van Ronkel, Based on the Novel Rocketship Galileo by Robert A. Heinlein, Producer – George Pal, Photography – Lionel Lindon, Music – Leith Stevens, Special Effects Supervisor – Lee Zavitz, Animation – Walter Lantz, Production Design – Ernst Fegte. Production Company – George Pal Productions/Eagle-Lion.

Cast

John Archer (Jim Barnes), Warner Anderson (Dr Charles Cargraves), Dick Wesson (Joe Sweeney), Tom Powers (General Thayer)

Plot

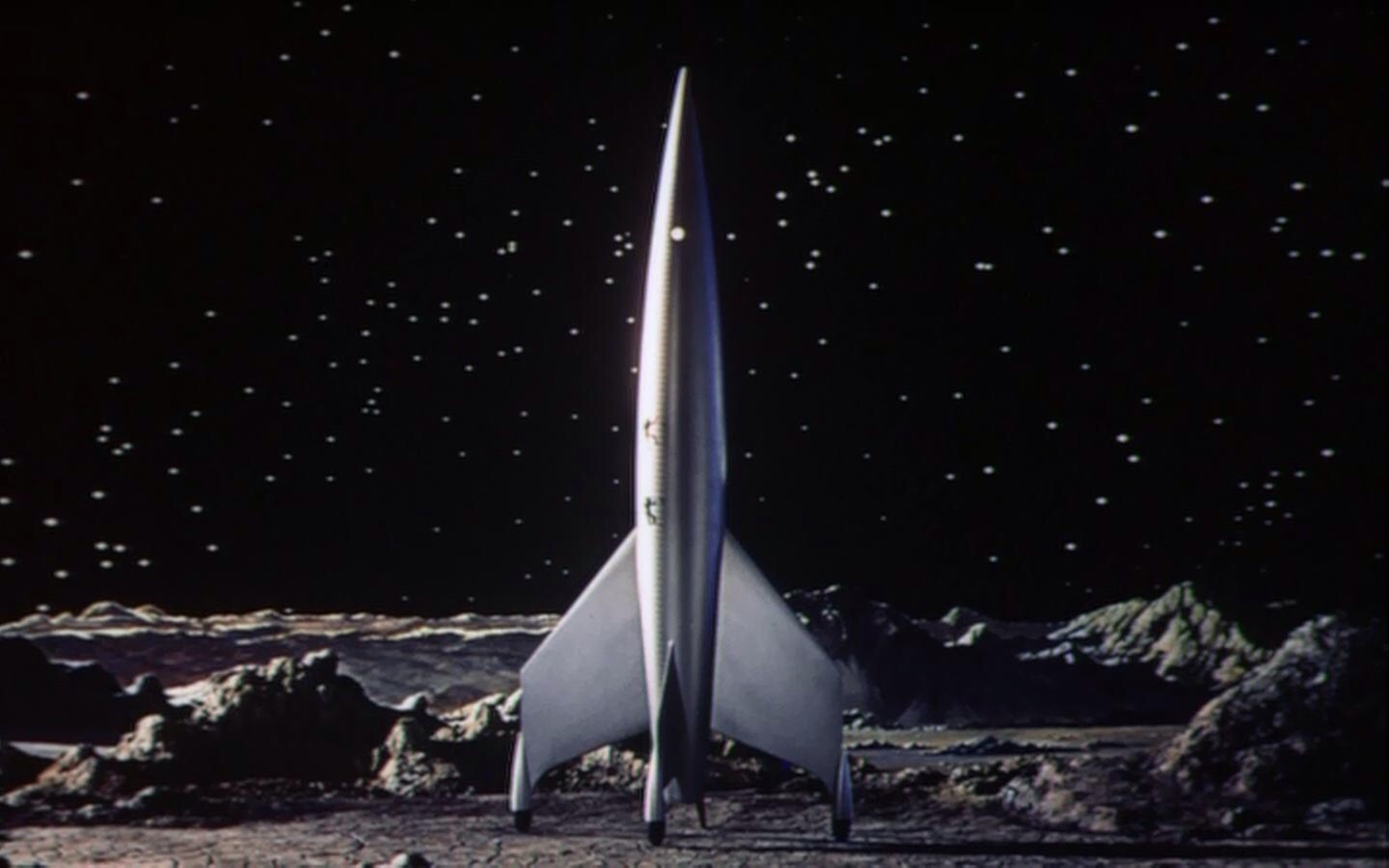

Aerospace manufacturer Jim Barnes comes up with the idea of building the first rocket to the Moon. The only way to finance the project is for him to persuade a group of other aerospace manufacturers of the strategic importance that the Moon will have as a missile platform for the first country that lands there. However, as they begin construction on the rocket, the government is fearful of what its atomic engine might do and try to stop them from launching. They launch nevertheless, undergoing a journey fraught with problems to eventually land on the Moon.

There had been several films dealing with spaceflight and trips to the Moon prior to Destination Moon. Only a few of these dealt with the idea in any serious way – Fritz Lang’s Woman in the Moon (1929), the little-seen Soviet Cosmic Voyage/The Space Ship (1936) and at the end of Things to Come (1936) are the only ones that readily come to mind. There were other space journeys such as the Danish Heaven Ship/A Trip to Mars (1918) and the Russian Aelita (1924) but these mostly concerned themselves with the Utopian/Dystopian societies that the astronauts might encounter at their destination. The majority of films dealing with space travel were either adventure films like Flash Gordon (1936) or non-serious whimsies such as Georges Melies’s A Trip to the Moon (1902) and An Impossible Voyage (1904). So when Destination Moon came it arrived with an epic leap of the imagination that went where no other film had ever attempted to go before.

Destination Moon‘s importance to science-fiction cinema is frequently overlooked. Many genre reviewers almost criminally dismiss Destination Moon and call it dull and boring. Certainly, there is some justification for this – the characters are dull and anonymous and when they have any distinction, they are written in virtual stock types such as The Comic Relief from Brooklyn. The early scenes in the film are dramatically stolid – the technical exposition comes delivered in boiler-plate dramatics such as the use of a Woody Woodpecker cartoon to explain how the rocket will work.

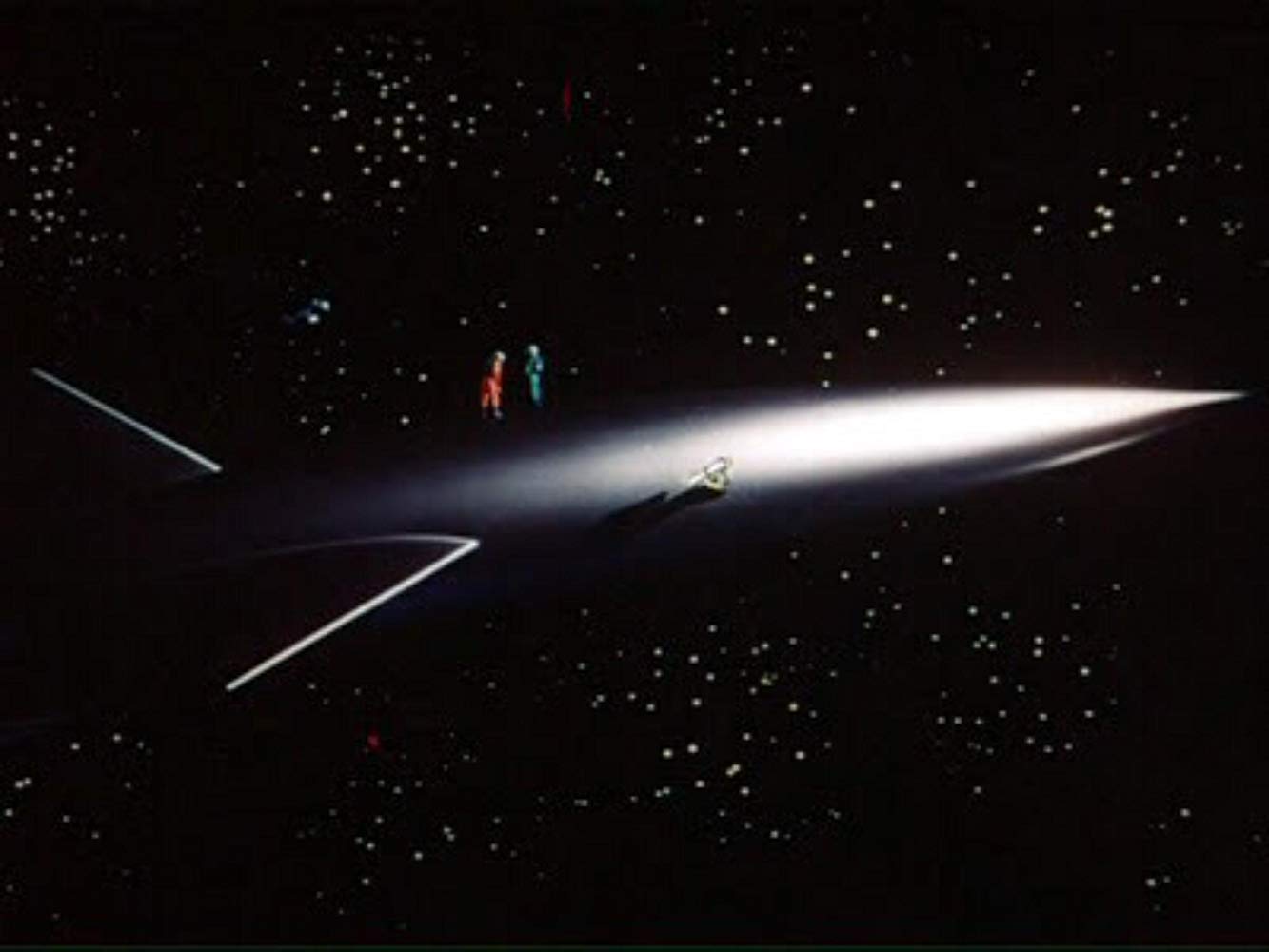

However, once Destination Moon gets up into orbit, it is completely gripping. The film has been constructed around a series of dramatic peaks – the EVA jaunt, the effort to rescue the man who floats away from the rocket, the climactic problems having to lose enough mass to lift off and the likelihood that one man will have to stay.

The accusation that the film is dull only reveals a reviewer’s lack of empathic projection. Such an accusation is surely one that has been blunted by expose to the real Moon Landing in 1969, in comparison to which the fictional equivalent certainly did look somewhat the lesser. But surely the fact that Destination Moon can be accused of being too close to the real thing to be interesting is just indicative of how much of an imaginative leap it was. There is surely no other science-fiction works around that can be accused of being so close to the real events that they are like watching documentaries.

Destination Moon was the first film of the so-called Golden Age of Science-Fiction Cinema that lasted from around 1950 to 1957. It has an immense optimism that paved the way for every other science-fiction film of the 1950s to follow and its success was something that made producer George Pal into science-fiction cinema’s leading voice of the era. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, space was something that American films rarely ventured into. In serials like Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers (1939), space was little more than an exotic realm like some African or Asian lost kingdom and the astronauts were akin to cowboys in Westerns, black-and-white heroes who tamed the high frontier with six guns and their fists.

By contrast, Destination Moon charted a plan for conquering space with rigorous scientific realism. It offered up a series of detailed engineering schematics for how to conquer the new world – of almost any science-fiction film of the 1950s, this is one where the science would actually work. Moreover, the film’s heroes are not cowboys but the heroes of the new post-War boom and the coming Space Age – engineers and aerospace industrialists. Destination Moon was an extraordinarily optimistic vision that conceptually opened up the space frontier and saw it as free and accessible for the conquering.

Although in actuality, for science-fiction cinema such a bold vision almost immediately fell inward upon the navel-gazing anxieties of the Cold War and the Atomic Age. Rather than venturing outward, science-fiction films became concerned with the enemy out there or the nightmare of the Bomb unleashed. The few visions of films that did venture out into space in the 1950s almost immediately saw only a mirror of this world – where humanity’s capacity for self-annihilation was echoed in strident tones – as in Rocketship X-M (1950) and This Island Earth (1955) – or the likes of Riders to the Stars (1954), The Quatermass Xperiment/The Creeping Unknown (1955), The Angry Red Planet (1959) and First Man Into Space (1959), which saw the universe out there as filled with dangers and that the human cost of conquering it was far too high. The contrast can not be made clearer than in producer George Pal’s own follow-up to Destination Moon, Conquest of Space (1955), where the bold optimism of Destination Moon almost immediately caves into a fear of the universe where Man is seen to be defying divine provenance.

Certainly, with Destination Moon, George Pal had the good sense here to hire Robert Heinlein on script. Robert A. Heinlein was the most acclaimed of the new generation of science-fiction writers to emerge out of John W. Campbell Jr’s Astounding pulp magazine in the previous decade. During the 1940s, Heinlein quickly charted a mastery of the genre with his intellectually bracing, densely credible worlds of projection and his notion of a far-stretching Future History. Throughout the next four decades, Heinlein claimed his place as the primo grandmaster of science-fiction with classics such as Have Spacesuit, Will Travel (1959), Starship Troopers (1959), Stranger in a Strange Land (1961), The Moon is a Harsh Mistress (1966) and Time Enough for Love (1973). Heinlein’s ardently libertarian views push people into wildly opposed camps but what is rarely in doubt is the considerable brilliance and articulation of his writing.

Destination Moon is also unique in that it is perhaps the first film in the history of all science-fiction cinema to raise the intellectual level of the literary work that it is based on, rather than the other way around. Rocketship Galileo (1947), the Robert Heinlein novel that Destination Moon is very loosely based on, is a juvenile story about an inventor building a rocket in his backyard and kids battling Nazis on the Moon, but the film instead raises the work to a serious piece about the construction of a rocket, extrapolated with the greatest realism that the technology of the time could provide. (At the time, Heinlein was a close associate of the very interesting figure of Jack Parsons, the leading rocket scientist in the US and a serious believer in a Moon landing when most others regarded it as science-fiction). About the only flaw in the film’s portrayal of The Moon is that it looks like a dried, cracked riverbed, implying the former presence of water.

Where Destination Moon gets it wrong is perhaps some of its most interesting points. It assumes that atomic rockets will be used instead of chemical rockets; there is no tv coverage, instead the head of the expedition gives a single radio interview (a reflection based on the prevalence of radio and the lack of a commercial foothold that television had made at the time). One of the film’s more quaint pieces of phraseology is its description of weightlessness as ‘free orbit’ instead of ‘freefall’.

Perhaps most interesting is the film’s underlying assumption about how a Moon mission would end up being financed. The film believes that financing would have to come from the private sector rather than from government. Most amusingly, government appears disinterested in the project; the private sector are also disinterested at first but are then convinced in a burst of patriotism when the strategic advantages of staking claim to the Moon before any other ‘foreign powers’ can claim it is as a potential missile base is pointed out to them. The government, when they do get involved, in a classic piece of libertarian paranoia, only want to do so because they are fearful of people building atomic rockets.

George Pal’s other genre films When Worlds Collide (1951), The War of the Worlds (1953), The Naked Jungle (1954), Conquest of Space (1955), tom thumb (1958), The Time Machine (1960), Atlantis, the Lost Continent (1961), The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962), 7 Faces of Dr Lao (1964), The Power (1968) and Doc Savage – The Man of Bronze (1975).

Director Irving Pichel was best known as an actor – his most well known genre role was as the butler in Dracula’s Daughter (1936). Pichel also made more than 30 films as a director. His other directorial genre credits include co-directing the famous human hunting for sport film The Most Dangerous Game (1932), co-directing the H. Rider Haggard adaptation She (1935) about a lost city and an immortal queen, the angel fantasy Earthbound (1940), the pious The Miracle of the Bells (1948) about Catholic miracles, the bubbly mermaid comedy Mr Peabody and the Mermaid (1948) and George Pal’s The Great Rupert (1950).

Other Robert Heinlein works adapted to the screen include:– Project Moon Base (1953), another work about a Moon landing from an original Heinlein screenplay; the animated tv mini-series Red Planet (1994) from Heinlein’s juvenile; the alien body snatchers film The Puppet Masters (1994) from Heinlein’s novel; Paul Verhoeven’s bludgeoning adaptation of Starship Troopers (1997); the fine Predestination (2014) based on Heinlein’s classic time paradox short story __All You Zombies__ (1959); and the Japanese adaptation of The Door Into Summer (2021). Neither co-writers James O’Hanlon or Rip Van Ronkel went onto to anything else of note, although in an interesting footnote Van Ronkel did make an appearance as a character in Hollywoodland (2006) based on the true life death of actor George Reeves.

Trailer here