Crew

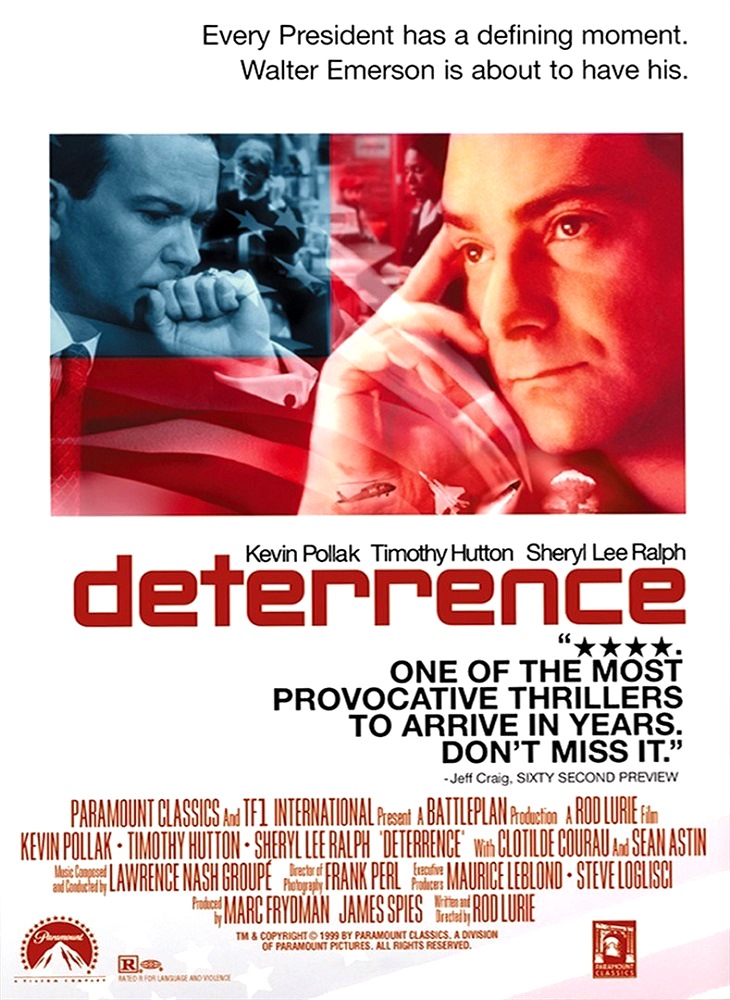

Director/Screenplay – Rod Lurie, Producers – Marc Frydman & James Spies, Photography – Frank Perl, Music – Lawrence Nash Groupe. Production Company – Battleplan Productions.

Cast

Kevin Pollak (President Walter Emerson), Timothy Hutton (Marshall Thompson), Sheryl Lee Ralph (Gayle Redford), Sean Astin (Ralph), Clotilde Courau (Katie), Badja Djola (Harvey), Michael Mantell (Taylor Woods), Kathryn Morris (Lizzie Woods), Uzi Gaal (Haffez Omari)

Plot

The year 2008. Walter Emerson, who became the US President after his predecessor died in office, is in the midst of re-election campaigning when he is trapped by a blizzard and forced to take refuge in a diner in Aztec, Colorado. There news suddenly comes that Iraq, under Saddam Hussein’s son, has just invaded Kuwait. Emerson, wishing to be seen as a strong leader rather than someone who took office without being voted in, takes the bold step of announcing that unless Iraqi troops withdraw within one hour and twenty minutes he will detonate a nuclear weapon on Baghdad. However, instead of retreating, Iraq retaliates by announcing it will launch nuclear weapons at major world cities.

Deterrence is a return to a type of film they don’t make anymore – the Nuclear War film. This type of film was in its heyday during the 1960s when the possibility of nuclear war in the real world hung by a thread over everybody’s heads. It was an era that produced the grim and utterly despairing likes of On the Beach (1959), Dr Strangelove or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), Fail-Safe (1964) and The War Game (1965). The nuclear war film tapered off in popularity in the 1970s but made a return in the 1980s, concomitant with Ronald Reagan’s massive nuclear rearmament campaign, with the likes of WarGames (1983), Testament (1983), and tv’s The Day After (1983), Special Bulletin (1983), Threads (1984) and Rules of Engagement (1989).

In the 1990s and 00s, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, the nuclear war film has become an almost completely extinct genre. The only other nuclear war films of the 90s and beyond – outside of sundry Mad Max 2 (1981) copies, which can be hardly regarded as serious thematic discussions on the theme – have been Crimson Tide (1995) and The Sum of All Fears (2002).

Like Dr Strangelove and Fail-Safe, the best of the 1960s nuclear war films, Deterrence constrains itself to a single location. (Where Dr Strangelove and Fail-Safe managed three locations apiece, Deterrence notably uses a single setting and also sets its drama within real time – ie. the 90 minute running time of the film). Deterrence closely resembles Fail-Safe, which mostly consisted of two men in a bare room but was absolutely gripping in its playing out of the agonising attempt to stop the mission. Director Rod Lurie conducts an effective job of turning the business of people talking into cellphones into gripping drama, thanks to tight, snappy editing, multi-layered dialogue and some effective plot twists.

Along with Crimson Tide, the 1990s nuclear war film seems concerned less with the horrors of nuclear war than with the debates over the ethics of releasing the bombs. Kevin Pollak gives a good performance as a President who resents having come to his position without having been voted in and is trying to make a tough stand to prove himself and then, having done so, does not want to show his weakness by backing down. The script effectively wheels out arguments and opposing points of view to ask questions in ways that US media have demonstrated great reluctance to do so regarding the justification of military intervention in the Gulf.

Had Deterrence continued along these lines it would probably have ended up a four star film. The problem is its ending, which must rank up there along with tacked-on happy ending in the original cinematic release of Blade Runner (1982), or The Final Countdown (1980) and eXistenZ (1999) as one of the great genre letdowns of all-time. If it had been made for tv or was a studio production, you could understand that this might be an ending that was enforced by censorship or a studio that did not like bleak endings, but this is an indie production and does not have those excuses. You fail to understand how a three-quarters good and literate film can suddenly fumble it so badly.

The ending it pulls out of a hat is something akin to a bad episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-94) where at the last moment Data might produce a heretofore unknown technical flourish of the hand out of nowhere that saves the day. Here Kevin Pollak’s President (who has only been President for four months, yet is privy to information that his national security advisors and chiefs of military staff are not) reveals that the missiles sold to the Iraqis were deliberately sold with dud warheads. It is a revelation that is not only bogus storytelling but also one that completely vilifies the President’s position and indeed the one put forward by Sean Astin’s redneck character that the only solution is to “crispy char the bastards.” So much doubt is put on Kevin Pollak’s choice throughout and the question of whether America’s military obsession with Iraq is right and effort made to point out the real human cost of nuclear war, that for the film to then turn around and call the total nuclear evisceration of Baghdad a righteous decision and have Pollak lecture about the US’s position as peacekeeper in the world (all delivered without distinguishable tone of irony or disapproval) is not only incomprehensible but odious.

Of course, Deterrence was made well before George W. Bush became the President of the United States. Subsequently, Bush’s deeply unpopular invasion of Iraq in 2003 succeeded in giving Deterrence an uncanny and ironic number of real-life parallels. Bush, like Pollak’s President, came to power, not after inheriting the role from his predecessor, but in an election where he won by only the slimmest of margins and legal chicanery and then promptly embarked on an internationally ill-advised unilateral foreign policy as though he had to prove his own determination and will.

In both cases – with the Bush White House and Kevin Pollak’s President here – Saddam Hussein has been demonised as all that is contrary to democracy and freedom – the fear of Iraq launching nuclear weapons against the rest of the world here makes remarkable contrast to the real world situation where White House intelligence lied and distorted existing evidence to make an entirely insubstantial case for Saddam Hussein possessing nuclear and chemical weapons. You can also draw parallels between Kevin Pollak’s President here nuking Baghdad and then pontificating about the US being a world peacekeeping force, and Bush’s internationally offensive stance of invading Iraq after thumbing his nose at the UN and international opinion, all the while hiding behind the excuse of Iraq ignoring UN decrees as justification for doing so.

Deterrence was a directorial debut for Rod Lurie, a former film critic who subsequently went onto make the likes of The Last Castle (2001), the remake of Straw Dogs (2011) and The Outpost (2019). Lurie’s films have shown a frequent interest in politics with the likes of The Contender (2000), the tv movies I’m Paige Wilson (2007) and Killing Reagan (2016), as writer of the tv movie Capital City (2004) and creator of the tv series Commander in Chief (2005-6).