USA. 2013.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Gavin Hood, Based on the Novel Ender’s Game (1985) by Orson Scott Card, Producers – Orson Scott Card, Robert Chartoff, Lynn Hendee, Alex Kurtzman, Linda McDonough, Roberto Orci, Gigi Pritzker & Ed Ulbrich, Photography – Donald McAlpine, Music – Steve Jablonsky, Visual Effects Supervisor – Matthew E. Butler, Visual Effects – Comen VFX (Supervisor – Tim Carras), Digital Domain, The Embassy (Supervisor – Stephen Pepper), Method (Supervisors – Mark Breakspear & Sue Rowe), Vectorcom/Post 23, Special Effects Supervisor – Yves Debono, Creature Effects – Alec Gillis & Tom Woodruff Jr, Special Costumes Effects – Quantum Creations FX, Inc, Production Design – Sean Haworth & Ben Procter. Production Company – Sierra Affinity/OddLot Entertainment/Digital Domain/Chartoff Productions/Taleswapper/K-O Paper Products.

Cast

Asa Butterfield (Andrew ‘Ender’ Wiggin), Harrison Ford (Colonel Hyrum Graff), Ben Kingsley (Mazer Rackham), Abigail Breslin (Valentine Wiggin), Hailee Steinfield (Petra Arkanian), Viola Davis (Major Gwen Anderson), Nonso Anozie (Sergeant Dap), Moises Arias (Bonzo Madrid), Aramis Knight (Bean), Conor Carroll (Bernard), Jimmy ‘Jax’ Pinchak (Peter Wiggin), Andrea Powell (Theresa Wiggin), Caleb J. Thaggard (Stilson), Suraj Partha (Alai), Tony Mirrcandani (Admiral Chamrajnagar)

Plot

Earth has come under attack by an alien species known as The Formics. In preparation for the fight back against The Formics, humanity has begun to train children, hoping to find the next military genius who can lead the Earth fleet. Young Andrew ‘Ender’ Wiggin is one of those selected by Colonel Hyrum Graff who believes that he has the mind needed to lead them. Ender is taken to the orbiting Battle School where he faces many challenges as he learns the art of combat in a series of games between teams in a zero gravity arena. There Ender proves brilliant at thinking outside the box and devising winning strategies. This has him promoted to command a series of training simulations in which he marshals the Earth spacefleet together for what will be the final war with the aliens.

I come not to condemn Orson Scott Card but praise his name. If I have to select a list of the Top 10 science-fiction writers currently still alive and publishing, I’d have to put Card’s name on there, alongside other authors such as William Gibson, China Mieville, Kim Stanley Robinson, Neal Stephenson and John Varley (to name some of the competitors off the top of my head). Card writes some exceptional science-fiction and fantasy (and with incredibly prolific output too). Card first appeared with the short story version of Ender’s Game (1977) in Analog magazine. He has published more than fifty novels since 1978 and created several different ongoing series in as varied genres as the five-book The Homecoming Saga, which rewrites The Book of Mormon as a science-fiction saga; a non-fantastical series set around the women of The Book of Genesis; and especially The Tales of Alvin Maker, a so-far six book series that tells an alternate history of the US around the late 18th/early 19th Century where magic works and winds in many known historical figures; as well as numerous standalone novels and short story collections.

Ender’s Game (1985), the novel-length expansion of the short story, won Card both the science-fiction community’s Hugo and Nebula Awards when it came out, as also did the book’s sequel Speaker for the Dead (1986), which Card expands out in remarkable way, showing Ender travelling the galaxy seeking redemption for his slaughter of an entire species. Card followed these up with the less interesting Xenocide (1991) and Children of the Mind (1996), as well as has written two other books A War of Gifts (2007) and Ender in Exile (2008), which tells aspects of Ender’s life in between the earlier works. Aside from that, Card has expanded the Ender saga out with another entire series that focuses on the character of Bean, which consists of Ender’s Shadow (1999), Shadow of the Hegemon (2001), Shadow Puppets (2002), Shadow of the Giant (2005) and Shadows in Flight (2012), which covers all the way from Bean’s birth as a genius-level infant (genius children feature a lot in Card’s books) to the war for control of the Earth following the end of the war with the Formics/Buggars to an entire book about Bean’s children.

Ender’s Game is the first media adaptation of one of Card’s works – the nearest he has come in any regard has been writing the novelisation of James Cameron’s The Abyss (1989). That said, Card has been involved in writing scripts for a number of short films that tell stories from The Book of Mormon and has even directed one of these. Ender’s Game has been optioned as a film production for over two decades, which was for a long time associated with Wolfgang Petersen, the German director of Das Boot (1981), Enemy Mine (1985) and Outbreak (1995), before finally emerging here. Card interestingly tells how he had it written into his contract that Ender had to be played by a boy around the age of twelve and kept dealing with producers who wanted to bump it up to someone in his teens. Some of Card’s other works would make excellent films – I had the valiant hope that Ender’s Game would be sufficient success that someone might be inspired to make Card’s Speaker for the Dead, which I would argue is his best book, as a sequel. Although in my personal dream projects, I would love to see the Alvin Maker books done as some kind of HBO series along the lines of Game of Thrones (2011-9). Subsequent to this, Card went on to create the sf series Extinct (2017) set in a far future where humanity is extinct, although this only lasted ten episodes.

All of which brings one to Orson Scott Card as an individual and his personal beliefs. These frequently leave me scratching my head. Card was raised a Mormon, indeed lays claim to being a great-great-grandson of Brigham Young, has been a missionary for the church and writes a column in Mormon Times. Having looked at The Book of Mormon, I can say I view its beliefs as a nonsense that have been disproven by archaeology and genetics to a sufficient degree of proof for me. Card seems a frequent contradiction in his beliefs. He holds true to a biblically-ordained outlook on the world, yet also believes in evolution; he writes an incredible anti-war parables like Ender’s Game and Speaker for the Dead, yet also stumped at the polls for George W. Bush’s 2004 re-election campaign because of his willingness to go to war with Iraq; he claims to be a Democrat but supported Bush and wrote a controversial essay in which he imagined a dystopian future under Barack Obama; he holds strong anti-gay views, yet writes gay sympathetic characters in Songmaster (1978) and (debatably) The Homecoming Saga.

Card’s outspoken opposition to gay marriage – he was a member of the National Organization for Marriage, which is opposed to same-sex marriage, and has written several provocative essays on the topic – has become a substantial hot button issue – it had people opposing his working on DC’s Superman comic-book and an online campaign by Geeks OUT! trying to prevent a boycott of the film of Ender’s Game. I don’t really want to defend Orson Scott Card here. I’m fully in the camp that supports same-sex marriage (in fact, I would take it further than probably most of the proponents – why can’t polygamists and people in non-traditional couples arrangements have some type of legal status either?). I once met Orson Scott Card at a convention and found him highly interesting as a speaker. It doesn’t mean I am on the same page politically with him – in fact, we ended up in a debate over the Terry Schiavo affair where he was strongly in the right-to-life camp citing facts that I later found had been made-up by the conservative establishment. What I do hold is that he is entitled to whatever viewpoints he likes and his complete freedom to express these in whatsoever way he sees fit. If we extend what we consider watchable and acceptable entertainment to only the people who share the same viewpoints as us then we are engaging in Political Correctness. Freedom of speech after all entails the freedom of people we are completely opposed to to expound their viewpoints.

There is a long history of science-fiction writers with extremist viewpoints – to select a couple of them, John W. Campbell, Jr, the editor regarded as the single most important and influential figure of the Golden Age of Science-Fiction and author of the story that became The Thing from Another World (1951) and The Thing (1982), once published in favour of Scientology and argued the merits of slavery; Robert A. Heinlein, who many will argue is the greatest science-fiction writer of all-time, held libertarian views that are far more extreme than most of the modern Tea Party. On screens, there are directors like Roman Polanski and Victor Salva who have been charged with having sex with minors, but also happen to make extremely good films.

What needs to be injected into the debate is a separation of the merits of an author’s work from their personal foibles and outlooks rather than holding the entire body of their work to account for one viewpoint among many or one incident in the past. Should the controversial viewpoints of actors like Tom Cruise and Mel Gibson detract from their work they have done? I don’t think they should – but you are free to disagree with me. I like Card’s writing and he comes across as sufficiently literate in the viewpoints he expounds that I am at least prepared to sit down and listen to what he has to say; that doesn’t mean I am going to agree with him. I have done and said enough stupid things I’ve regretted or realised I was wrong on later throughout my life – I’d like people to extend to me at least not tainting all that I write by this. By similar token, I think the same should be extended to Orson Scott Card.

All of that said, it is interesting to watch the way the studio has backpedalled and tried to distance itself from Card’s anti-gay views. Harrison Ford firmly spoke out in public, while most of the cast and crew issued statements saying they don’t support such a position. The studio even went so far as to announce it will host a benefit premiere for the LGBT community (although despite such announcement, I have yet to find where this took place). All of which suggests a studio that is wanting to distance themselves from any potential backlash against the film – and when there is a $110 million budget at stake and the anti-Card movement was about the one issue that dominated the film’s pre-release, it is sound PR sense. On the other hand, it does seem extraordinarily bold of them given that Card and his Taleswapper production company is also one of the producers of the film. It is the sort of thing you would expect of a company adapting a work from an author that had been dead for more than a decade rather than one who is actively involved in the production. Card himself even went so far as to issue a statement, which can be read here, but it feels disingenuous – Card merely hides behind saying that “the law has changed so my opposition doesn’t matter anymore” and at no point offers any defence, retraction of or apology for his views.

Onto Ender’s Game the film itself. I had mixed hopes for the film. In the director’s chair, as well as handling the screenplay, is Gavin Hood who previously ventured into genre material with the much hated X-Men Origins: Wolverine (2009), which I do rate slightly higher than most on the blogosphere do, as well as other non-genre films such as Tsotsi (2005), Rendition (2007) and the halfway reasonable drone warfare film Eye in the Sky (2015). Nor exactly did the producing names of Alex Kurtzman and Roberto Orci inspire a lot of confidence. Kurtzman and Orci have a bad habit of starting out with intelligent science-fiction premises – their script for The Island (2005) and big screen adaptations of Star Trek (1966-9), as well as the children’s series Transformers (1984-7) – and writing them down for directors who turn them into mindless action vehicles as per Transformers (2007), Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen (2009), Star Trek (2009) and Star Trek: Into Darkness (2013). Nor did the trailer that went out for Ender’s Game do much to enthuse one – it seemed to emphasise all the flashy hardware and explosions side of the story when in fact the book is an internal one about a child’s growth and learning of strategy.

The surprise then is that Ender’s Game ends up better on screen than one expected before sitting down to watch. There are a few changes such as the aliens being renamed The Formics as opposed to the more contentious Buggars that Card named them in the book. Gavin Hood remains surprisingly faithful to the book on most regards and never deviates from what is described in any substantial way. On the other hand, he has clearly made some excisions. Most noticeably, this occurs in terms of some of the book’s supporting characters – Ender’s sister Valentine and especially brother Peter are sidelined to little more than footnotes whereas in the book both become articulate political voices who influence the course of events on Earth. Similarly watered down is the character of Bean who became a major ally/nemesis of Ender in the story – you look at Aramis Knight’s anonymous performance as Bean here and wonder what there would be about such a character that could rival Ender let alone inspire a five-book (or film) pendant series.

There are some things that the film does very well. Asa Butterfield, previously the young kid in Martin Scorsese’s Hugo (2011) – where he also appeared with Ben Kingsley as a reclusive figure who becomes his mentor – makes for an excellent Ender, just the way you expect him to be in reading the book. Gavin Hood does a worthwhile job in replicating the combat training scenarios and we see Ender’s ingenuity come through. The main problem with these is that Ender’s Game comes out only a few weeks after Gravity (2013) and its sensational depiction of people navigating in zero gravity, after which the zero g scenes here seem but a pale shadow. It is purely the timing and almost certainly the film would have been more impressive in this regard had it been seen at some other or earlier point.

The main problem is that, while the film is extremely faithful to the essence of the book, I am not sure if Ender’s Game makes for a great film on its own. Part of it is the time it was made. Orson Scott Card was writing before the internet and back in 1985 when the videogame was down at the simple 2D graphics of The Legend of Zelda and DragonQuest. In many ways, Card was prophetic – the entire premise of the film looks forward to immersive videogame experiences, while the character of Valentine was a blogger way before anyone had coined the term (although you can guarantee that any blogger or online essayist would sell their firstborn to be able to sway the opinions of world leaders the way Card has Valentine doing). The fact that the real world has caught up with and surpassed the ideas of the film tends to obviate its conviction. The big twist – “it wasn’t a game after all” – falls somewhat flat for the simple reason that there have been too many videogame/virtual reality films as reality in the ensuing decade and simply because Gavin Hood invests so much drama in the big effects sequences of the ships in combat with the aliens and not enough in making them seem just like they were training simulations.

The other thing is the big twist. The idea of the child genius character with the big destiny ahead of him is written across every aspect of the film. We have seen the kid with the massive talents he is unaware of and vast destiny ahead of him played out throughout the Harry Potter films – served up once again, it starts to seem a little too familiar. Alan Moore did a rather apt parody of this in the third volume of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen where he has a character that is an analogue of Harry Potter who becomes the Antichrist after his mind snaps following the revelation that his entire life had been manipulated. The point that Alan Moore makes about Harry Potter would surely be even more extreme if applied to Ender Wiggin – would not a kid who suddenly discovered that he had been lied to and manipulated into exterminating an entire sentient species go completely insane as a result of the experience?

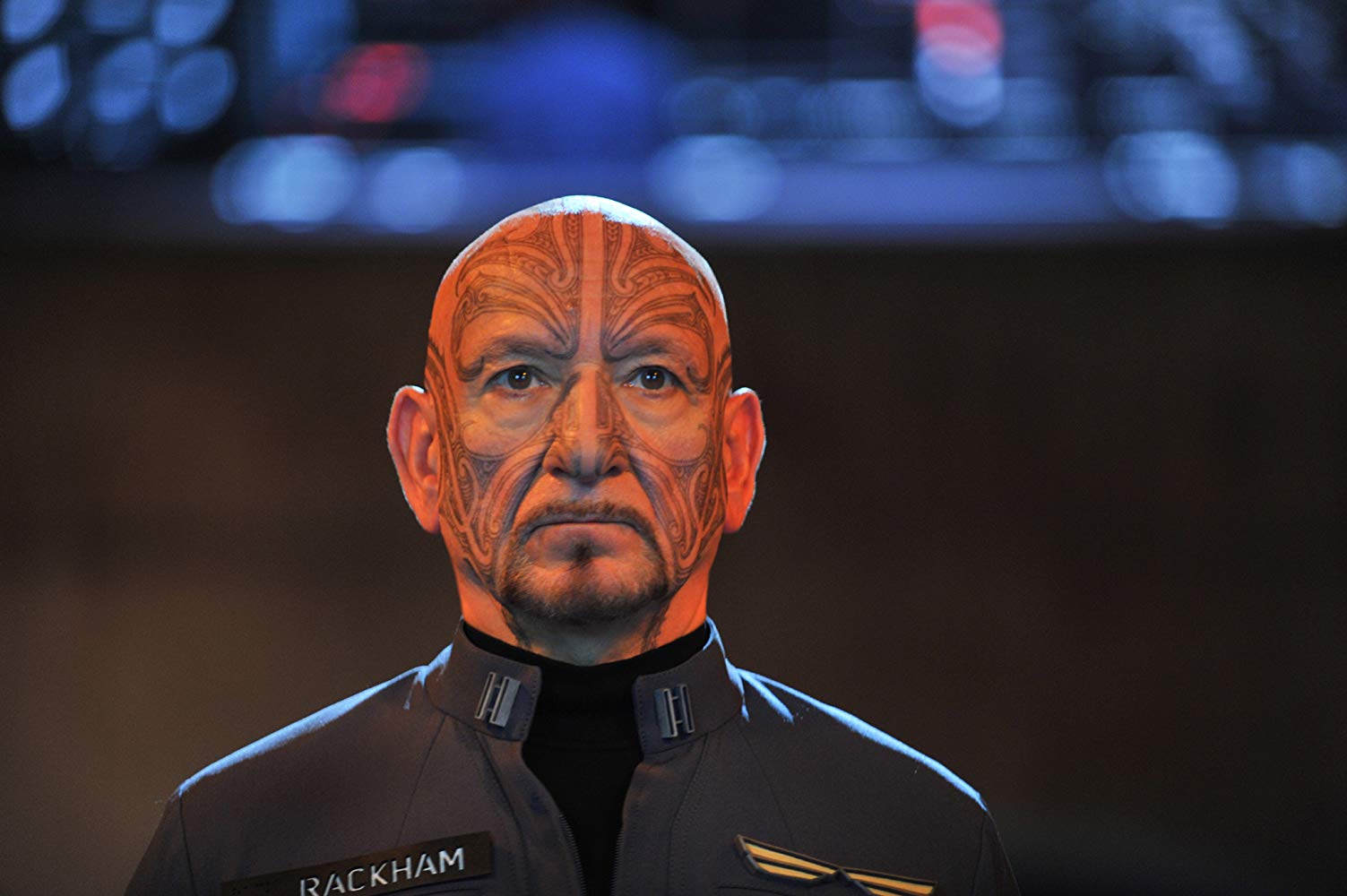

The other complaint I have against the film as a New Zealander is the casting of Ben Kingsley as a Maori. Much and all as I respect Kingsley as a great actor – temporarily forgetting BloodRayne (2005) – he comes across as the whitest, most non-Polynesian Maori ever born. In that the film goes to the scrupulous extent of casting a diverse range of ethnic peoples in the kid roles, I don’t understand why they couldn’t have cast a real Maori in the part – there are certainly enough Maori actors doing sterling performances on the world stage with the likes of Temuera Morrison, Cliff Curtis, Rawiri Paritene and Nathaniel Lees that it wouldn’t have been too hard to cast the part. Moreover, Kingsley’s misguided attempt to speak with a New Zealand accent sound more like he is from South Africa.

In the end, Ender’s Game is a mixed bag. It works reasonably well as an illustrated version of the book for those who have read it. On the other hand, I have my doubts whether anybody who comes to it as a film without reading the book is going to become a rabid fan. As a film, it seems to lack the dramatic oomph that makes it a soaring work. I never fully felt inside Ender’s struggle, his discovery of the secrets of strategy that turn him into a military genius on anything more than a purely functional plotting level. And I suspect that this is the fatal flaw that will doom Ender’s Game to simply an also-ran in the 2013 box-office race.

Trailer here