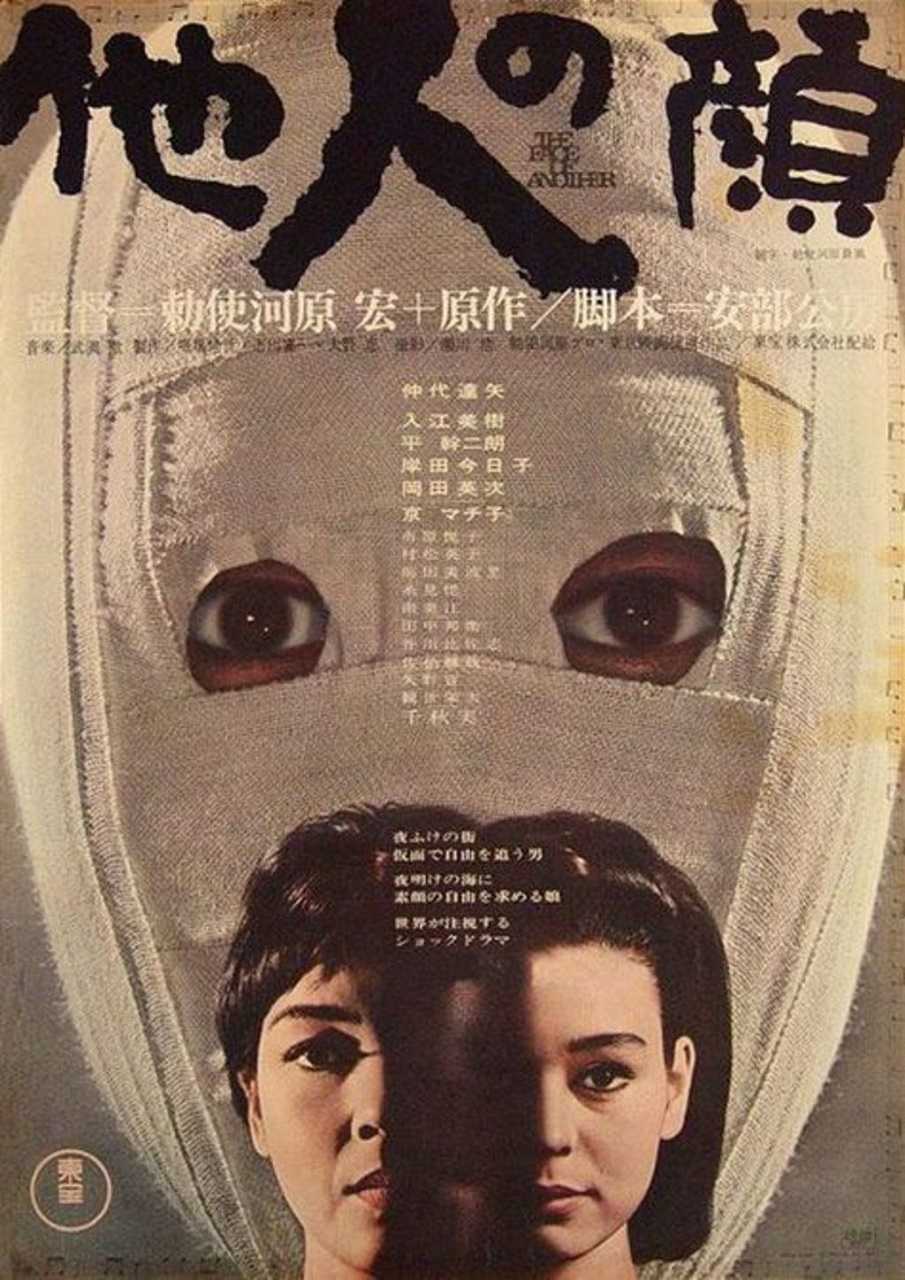

(Tanin No Kao)

Japan. 1966.

Crew

Director – Hiroshi Teshigahara, Screenplay – Kobo Abe, Based on the Novel by Kobo Abe, Producers – Nobuyo Horiba, Kiichi Ichikawa & Tadashi Oono, Photography (b&w) – Hiroshi Segawa, Music – Toru Takemitsu, Production Design – Masao Yamazaki. Production Company – Teshigahara Productions.

Cast

Tatsuya Nakadai (Mr Okuyama), Mikijiro Hira (Dr Hori), Machiko Kyo (Mrs Okuyama), Miki Irie (Girl with Scar), Etsuko Ichihara (Yoko), Kyoko Koshida (Nurse), Eiji Okada (The Boss), Eiko Muramatsu (Secretary), Minoru Chiaki (Superintendent), Kakuya Saeki (Brother of Girl with Scar)

Plot

Mr Okuyama’s face has been hideously burned in an industrial accident, forcing him to cover it behind bandages. He consults the surgeon Dr Hori, feeling that by losing his face he has lost his identity and the ability to be a normal human being. Dr Hori devises a new technique that allows him to model the features of a paid subject to create a lifelike mask. The mask is placed onto Mr Okuyama and looks indistinguishable from a real face, although can only be worn for twelve hours at a time. Mr Okuyama tells his wife that he is going away for a few days and then rents two different apartments in the same building, one while wearing his bandages, the other while wearing his facemask. Dr Hori believes that the mask is making Mr Okuyama assume its own actions. Mr Okuyama then determines that he is going to seduce his wife while wearing the mask and have she think him a different person.

The Face of Another is an underrated classic from Japanese director Hiroshi Teshigahara. Teshigahara’s father was the founder of the Sogetsu School of ikebana (Japanese flower arranging), where Hiroshi became the school’s director in 1958 and was later appointed its Grand Master. Throughout his life, Teshigahara was also an accomplished exhibition artist and sculptor. He directed several documentary short subjects in the 1950s and then made his feature length debut with Pitfall (1962), a film with some surrealist and fantasy elements concerning labour disputes at a mine. It was however with his next film Woman in the Dunes (1964), about a man who is trapped by villagers in a pit at the bottom of a cliff and his relationship with his fellow woman prisoner, that Hiroshi Teshigahara had a genuine international hit that also saw him nominated for a Best Director Oscar.

Teshigahara’s next film was The Face of Another, although this was only a mixed success. He went onto make The Ruined Map (1968), an existential detective story; Summer Wars (1972) about Vietnam War deserters; Rikyu (1989), the biopic of a Japanese master of tea ceremonies and its follow-up Princess Goh (1992), although from the 1970s until his death in 2001, Teshigahara began to concentrate on his other arts.

With The Face of Another, Hiroshi Teshigahara adapts a 1964 novel from Kobo Abe, a writer not largely known outside of Japan who wrote science-fiction works such as Inter Ice Age 4 (1959), The Ruined Map (1967) and Kangaroo Notebook (1991) and collaborated on the scripts for Teshigahara’s first four films.

The Face of Another joins a number of other films from the late 1950s onwards that deal with surgeons engaged in facial experiments. This mini-genre began with the French arthouse hit Eyes Without a Face (1959) and quickly made its way to the province of B horror movies with the likes of Atom Age Vampire (1960), Circus of Horrors (1960), The Awful Dr Orloff (1962) and Corruption (1968). Another popular 1960s theme that plays out is that of identity and experimental processes that erode this – see the likes of The Manchurian Candidate (1962), The Mind Benders (1962), Seconds (1966), tv’s The Prisoner (1967-8), The Groundstar Conspiracy (1972), The Mind Snatchers (1972) and Who? (1974).

The entire film seems an existential meditation on the nature of face and identity. Kobo Abe’s script is constantly philosophically questioning the idea of the face and what it means to personal identity, asking some haunting questions such as how human one is or isn’t depending to what extent they have a face. There are some fascinating scenes where Tatsuya Nakadai and surgeon Mikijiro Hira start tossing out ominous lines such as “The mask wants to take on a life of its own” or “What if the mask lives on by taking over your body?” If The Face of Another was a 1940s mad scientist cheapie, this would no doubt be interpreted with deadening literalness with the mask coming to life to possess its wearer but here the idea is contained amid Kobo Abe’s dazzling swim of metaphors.

The first half of the film is an existential horror story about how a man who has lost his face feels like he no longer has any sense of identity, while the second half meditates on the mutability of identity as he discovers how the lifelike mask can allow him to become anybody he wants. Kobo Abe’s script is constantly exploring and playing with these ideas, making analogies to such things as the executioner’s mask, the hijab and the way that women wear makeup. We follow the protagonist on a journey into some fascinating and at times disturbing mental space – like when Tatsuya Nakadai starts contemplating that maybe he should disfigure his wife’s face as well so that she does not have to go through the pretence that nothing has changed. There is something genuinely creepy to the scenes near the end where Tatsuya Nakadai sets out to seduce his wife (Machiko Kyo) while wearing his new mask identity.

Hiroshi Teshigahara shoots the entire film in black-and-white at a time when this was becoming obsolete in cinema, possibly one of the reasons that The Face of Another was not a success in its time. One of the most striking aspects of the film is the coolly alienating modernist designs of the doctor’s office – shelves filled with moulds of ears and hands, walls of glass with anatomical diagrams on them that are often placed between characters, hero Tatsuya Nakadai modelling himself against a glass diagram of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, a patient sitting in a blackened room on a giant-sized model of a heart.

Hiroshi Teshigahara also throws in random surrealistic images – a woman sitting on a bed while aerial shots moving between skyscrapers are back-projected behind her, the door of the doctor’s surgery opening onto the closeup image of a woman’s hair drifting in water. The film reaches a surreal climactic confrontation between Tatsuya Nakadai and Mikijiro Hira with them standing in the street surrounded by crowds of passers-by who all have blank faces. One of the more interesting aspects of the film is how Hiroshi Teshigahara gives us only partial glimpses of Tatsuya Nakadai without his bandages – we only get to see him from behind or else with the camera looking down directly from above.

The film also has a B-plot about a girl (Miki Irie) who is treated badly because she has the right side of her face disfigured by a scar. We are first introduced to her walking along the street, followed by wolf-whistling teenagers before she turns and the fall of her hair parts to show her scarring. Her story culminates in a scene where she sleeps with her brother because he is the only one who treats her with kindness before she then drowns herself in the ocean. This plot is not particularly well developed, nor connected in any way except thematically to the principal scenes with Tatsuya Nakadai.

Trailer here