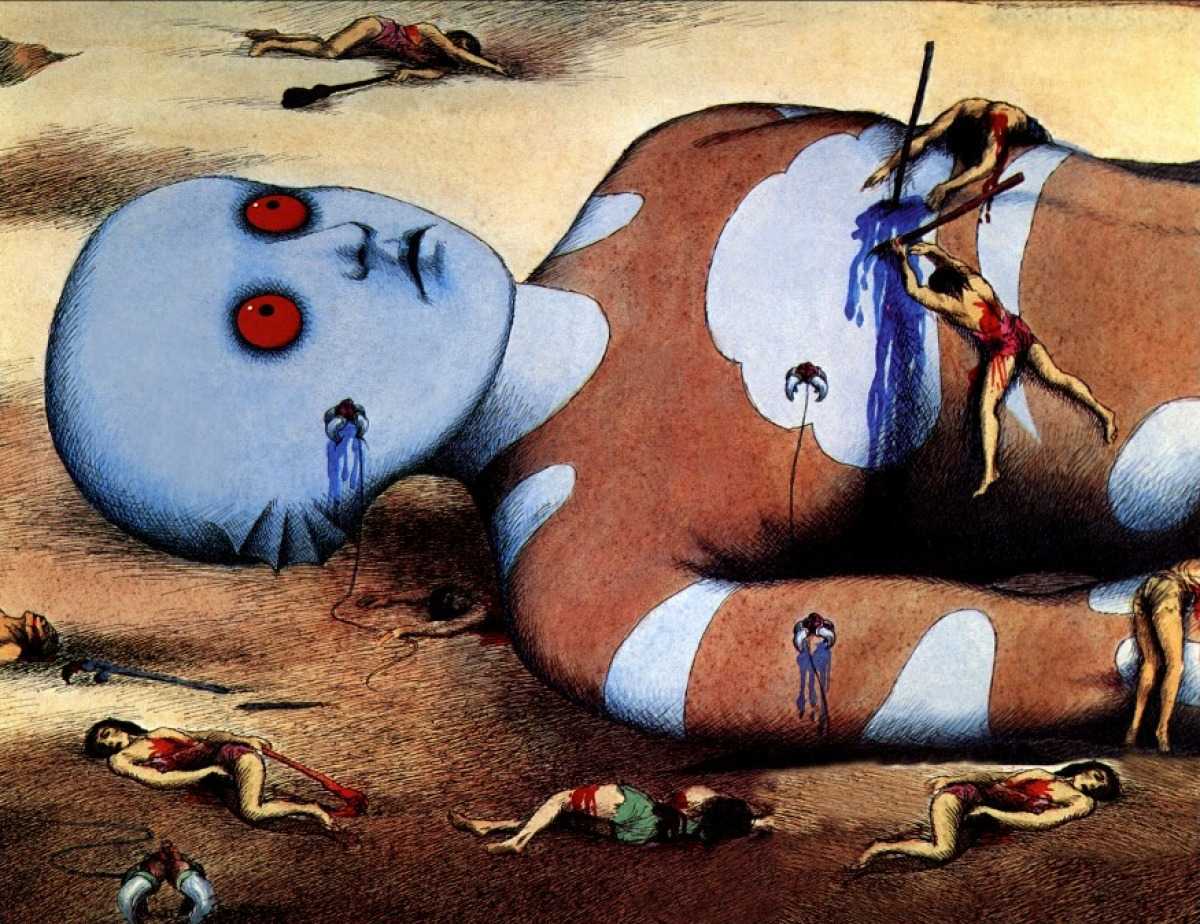

(La Planete Sauvage)

France/Czechoslovakia. 1973.

Crew

Director – Rene Laloux, Screenplay/Animation/Art Direction – Rene Laloux & Roland Topor, Based on the Novel Oms en Serie by Stefan Wul, Producers – Simon Domiani & Andre Valio-Caviglione, Photography – Boris Baromykin & Lubomir Rejthar, Music – Alain Gorageur. Production Company – Les Films Armorial/Ceskeslovensky Filmexport/Service de Recherche DRTF.

Plot

On the planet Ygam, the tiny humanoid Oms are treated as no more than pets by the giant blue-skinned Draags. An Om mother is cruelly killed by Draags. The young Draag girl Tiba finds the mother’s child and decides to adopt it, naming it Ter. As he grows up, Ter inadvertently becomes educated while being held in Tiba’s hands as she is using her education headphones that transmit information directly into the mind. As Tiba grows up, she loses interest in her toys. Ter runs away with the education machine and joins the Oms that live in the wild. At the same time, the Draags begin mass extermination of the Oms, seeing them as pests. Now having been educated by the machine, the Oms rise up in rebellion.

French animator Rene Laloux (1929-2004) emerged in the 1960s with surreal shorts such as Les Temps Morts (Dead Times) (1964), a satire about death in culture, and Les Escargots (The Snails) (1965) about an invasion of giant snails. Laloux and his collaborator Roland Topor made their first feature film with Fantastic Planet. The film began production in Czechoslovakia but Laolux and Topor were forced to relocate to Paris after the Soviet invasion in 1968. The film won the Grand Prix at Cannes when it premiered in 1973.

Between 1973 and his death in 2004, Laloux made two other feature-length films, The Time Masters (1982) and Gandahar/Light Years (1988), both of which fall within science-fiction themes. Laloux’s output may be sporadic but his films are the only ones that tap right into the spirit and style of the French comic-book Metal Hurlant (1974-2004), perfectly capturing Metal Hurlant‘s wild trippy visuals, its adult nature and spacy sf-come-sword and sorcery sweep.

Fantastic Planet is an extraordinary film. Even though the film’s animation is often limited, there is great imagination on display. Rene Laloux captures an all-too-rare sense of the sheer alienness of another world. The background of the film is filled with bizarre creations – a giant creature with a body shaped like a cage that laughs maniacally as it swats down and kills passing flying creatures; a journey through a landscape that appears like a giant maze pattern – but where various loops of the maze then come to life and start rippling in the rain; mulchers that cover people with their effluvium, which then becomes clothing; scenes where combatants are tied together with snapping seahorse-like creatures pinned to their chests and made to fight to the death; a battle with a giant gryphon-like creature that flies on winged ears and sucks entire nests of tiny Oms up with its tubular tongue.

The Draag culture of the mind is depicted with an appropriately otherworldly transcendental sweep – meditation rituals where they float off in transparent spheres or mutate into multi-coloured patterns, toys that create portable storms, chests that devour people who try to open them. The climactic image of the Draag meditation moon where the flying spheres arrive, meeting up with similar aliens from all over the universe and inhabiting the headless statues to dance together, is one moment of great surreal beauty.

The scenes of the Draag de-omization are shocking – the sequence comes filled with bizarre inventions including machines that fire deadly gas pellets or that send out a spotlight that obliterates everything it falls upon, giant rollerballs crushing Oms underneath them, huge vacuum cleaners. The film offers the portrait of a genuinely alien world – compare this to the various modern incarnations of Star Trek where, despite twenty years advance on Fantastic Planet, alienness never amounts to anything more than a few peculiar facial appliances.

Unfortunately, the savage and wildly imaginative background of the planet is the whole of the film. Where Laloux falls down is with an almost inert story. Whenever he does get around to telling it, this moves along in a sluggish way. For example, the film never seems to care about the romance between Ter and the wilderness girl enough to even give her a name. The ending is interesting – almost a complete reversal of the twist ending of Planet of the Apes (1968) wherein the alien world is revealed to take place at the beginning rather than the end of our world. Although as a serious idea, this is appalling anthropology.

Laloux’s collaborator on the film was the Belgian writer, actor and artist Roland Topor. Topor had collaborated with Laloux since his very first short (although not on any of his films subsequent to this). Topor would go onto a number of other works within the fantasy genre, including writing the novel that became the basis of Roman Polanski’s surreal identity exchange film The Tenant (1976); making acting appearances in Maurizio Nichetti’s comic satire Ratataplan (1979) and as Renfield in Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979); as well as writing and art directing the hilariously obscene puppet retelling of the Marquis de Sade story, Marquis (1989).

Trailer here