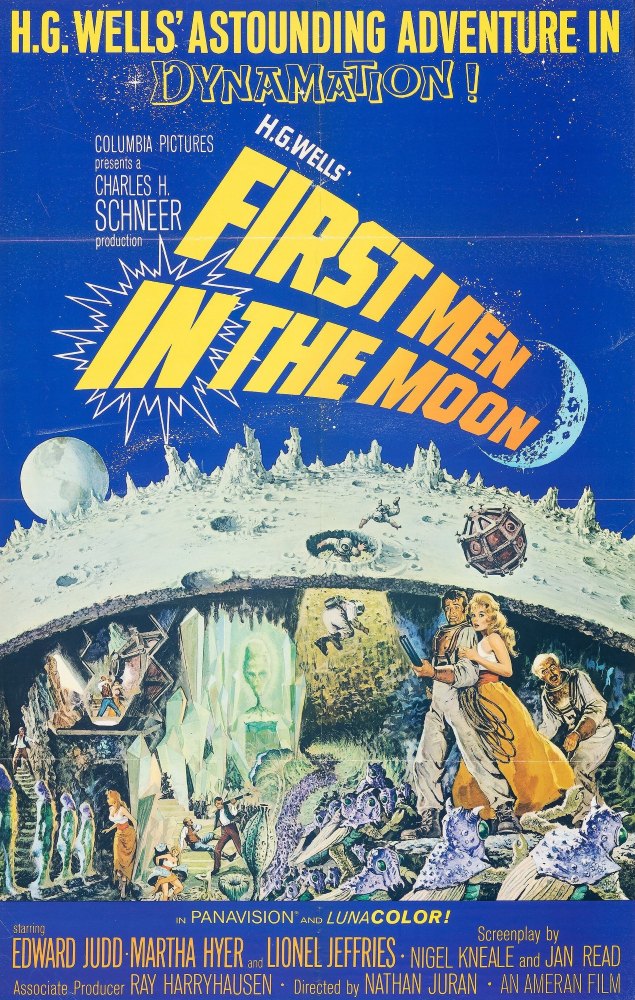

UK. 1964.

Crew

Director – Nathan Juran, Screenplay – Nigel Kneale & Jan Read, Based on the Novel The First Men in the Moon (1901) by H.G. Wells, Producer – Charles H. Schneer, Photography – Wilkie Cooper, Music – Laurie Johnson, Visual Effects – Ray Harryhausen, Special Effects – Kit West, Art Director – John Blezard. Production Company – Ameran.

Cast

Lionel Jeffries (Professor Joseph Cavor), Edward Judd (Arnold Bedford), Martha Hyer (Katherine Calender)

Plot

A UN expedition makes the first manned Moon landing in 1964. Instead, they discover a British flag and a summons for a Katherine Calender that is dated 1899 on the surface and realize that they are not the first there. The late Katherine Calender’s husband Arnold Bedford is tracked down in a geriatric home. He tells how his neighbour, scientist Arnold Cavor, discovered a metal capable of shielding the effects of gravity. Coating a sphere with the metal and using shutters to control direction, Cavor, Bedford and Katherine were able to escape Earth’s gravity field and travel to the Moon. On the Moon, they encountered and were made prisoners by a race of three-foot tall Selenites.

The First Men in the Moon (1901) was one of H.G. Wells’s lesser known classics, a book where Wells used the theme of lunar exploration to create a nightmare parable about ergonomics and adaptive evolution. The story was stolen and never credited by Georges Melies for the basis of his seminal science-fiction film A Trip to the Moon (1902), albeit given a much lighter treatment than Wells did. The story was also filmed in Britain as The First Men in the Moon (1919), although this version has been lost today and does not even exist as stills any longer. So it remains to this to offer a definitive version of the story although, as it transpires, by no means any more serious a one than Melies’s burlesque version, which had the ship being loaded into a cannon by dancing girls. Certainly, there is little to be seen here of H.G. Wells’s social parable and exploration of the idea of how a society might be formed along the lines of an insect hive.

The First Men in the Moon was mounted by American stop-motion animator Ray Harryhausen and his producer Charles H. Schneer, who had just come from acclaimed classics such as The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) and Jason and the Argonauts (1963). (See the bottom of the page for Ray Harryhausen’s other films). The script was adapted by Nigel Kneale, the British writer who attained fame in the 1950s for his Quatermass tv plays and the Hammer films adapted from these. [See The Quatermass Xperiment/The Creeping Unknown (1955)].

The First Men in the Moon came out a few years after Disney’s adaptation of Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954). This had kicked off a spate of period science-fiction classics adapted from Verne, which included the likes of Around the World in 80 Days (1956) and Journey to the Center of the Earth (1959). After George Pal’s successful period adaptation of The Time Machine (1960), other filmmakers turned to the works of Verne’s contemporary H.G. Wells. 20,000 Leagues and The Time Machine remain this cycle’s high points but its downside was that many, if not most, of the films ended as burlesque – Verne had to suffer the increasingly buffoonish likes of the 20th Century Fox Journey to the Center of the Earth, Irwin Allen’s Five Weeks in a Balloon (1962), then Jules Verne’s Rocket to the Moon/Those Fantastic Flying Fools (1967) – and with The First Men in the Moon it was H.G. Wells’s turn.

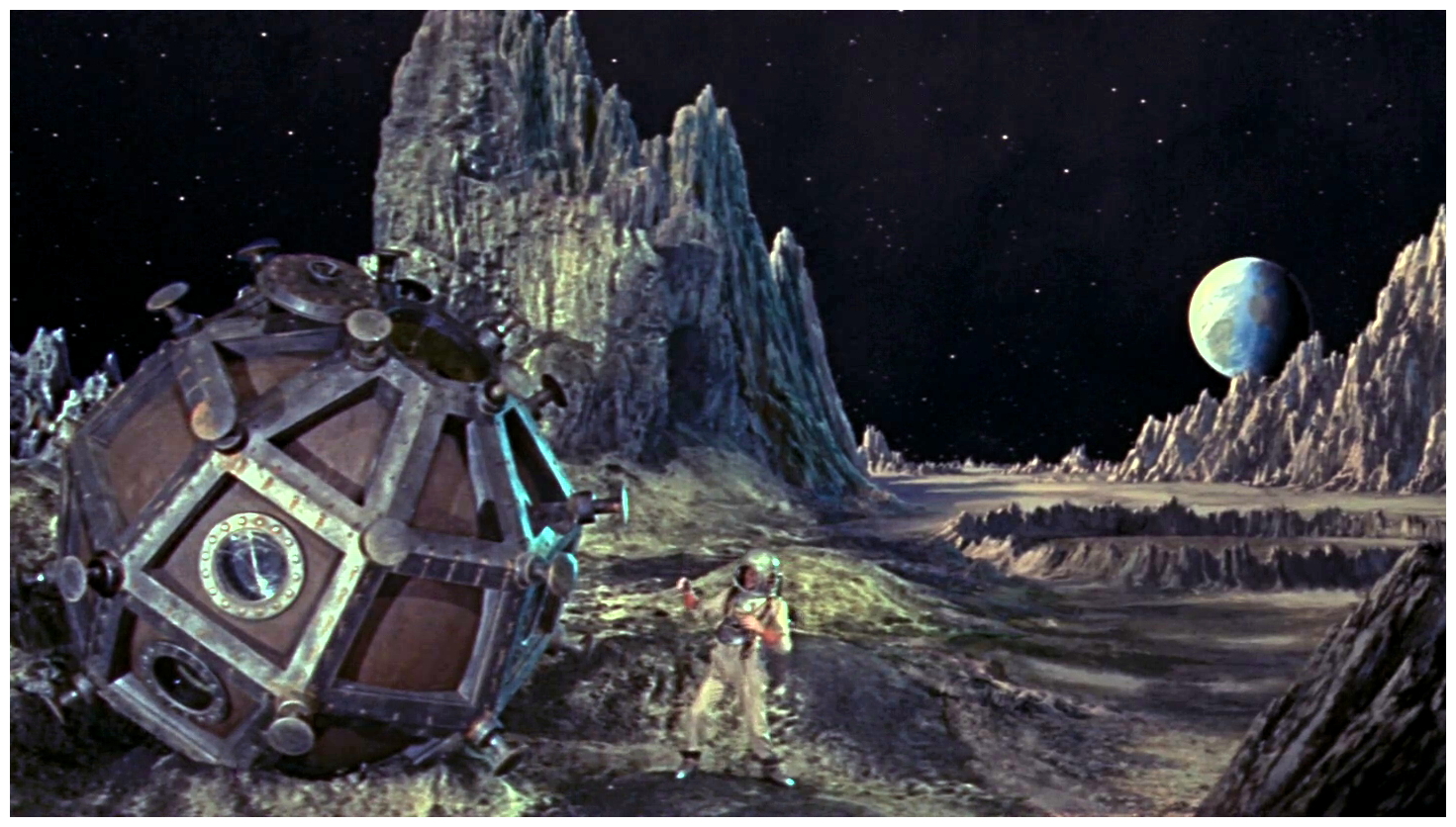

Certainly, the Lunar scenes are good and display a degree of imagination in places – images of vast bubbling cylinders of liquid to generate air, solar lasers and so on. The issues of weightlessness and air and sound in a vacuum are conducted with a little more credibility than most pre-1969 Moon landing science-fiction, although the script has the tendency to bring up the fact that sound does not pass in a vacuum and then ignore it anyway. The cave sets and blending of opticals used to depict the Selenite city are very good too.

Harryhausen animates a Moon calf but for time’s sake was forced to abandon the idea of animating most of the Selenties and have them played by children. As a result, the stop-motion creations here count as the most anonymous, least showcasey examples of Ray Harryhausen’s work. The optical effects are variable – while individual model scenes impress, thick matte lines abound and the models ache for the advent of motion control camerawork.

The film’s major minus point are the Earthside scenes. Here the humour comes written in broad, irritable strokes. The blithering bumptiousness of Lionel Jeffries’ Cavor quickly becomes tedious. The impressive creation of the Selenite society is considerably undermined by the human reaction to it – Cavor’s response is merely to wither up and spinelessly apologise, while Bedford’s is one of out-and-out xenophobia, with he happily killing and throwing Selenites over cliffs, something the film does not seem to take any great exception to. The final twist ending, added clearly as a sardonic echo on the ending of Wells’s The War of the Worlds (1898), wherein is revealed that Cavor’s cold succeeded in infecting and killing the Selenites, seems a final mocking insult, and in the film’s playing up of Bedford’s own undisguised glee, one that adds offence to affront.

The First Men in the Moon was later superbly remade as a BBC tv movie The First Men in the Moon (2010) with Mark Gatiss as Cavor and Rory Kinnear as Bedford.

Ray Harryhausen’s other films are:– the atomic dinosaur film The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953); the giant atomic octopus film It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955); the alien invader film Earth Vs. The Flying Saucers (1956); the alien monster film 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957); The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958); The 3 Worlds of Gulliver (1960); the Jules Verne adaptation Mysterious Island (1961); the Greek myth adventure Jason and the Argonauts (1963); the caveman vs dinosaurs epic One Million Years B.C. (1966); the dinosaur film The Valley of Gwangi (1969); the two Sinbad sequels The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973) and Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977); and the Greek myth adventure Clash of the Titans (1981). Ray Harryhausen: Special Effects Titan (2011) was a documentary about his work.

Nathan Juran’s other films are:– the historical horror film The Black Castle (1952), the giant bug film The Deadly Mantis (1957), Harryhausen’s 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957), the classic bad films The Brain from Planet Arous (1957) and Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958), Harryhausen’s The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958), Jack the Giant Killer (1962) and The Boy Who Cried Werewolf (1973).

Nigel Kneale’s other film scripts were The Abominable Snowman (1957), Quatermass 2/The Enemy from Space (1957), Hammer’s The Witches/The Devil’s Own (1966), Quatermass and the Pit (1967) and uncredited work on Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982). Kneale’s teleplays were:– The Quatermass Experiment (1953), 1984 (1954) from the George Orwell novel, The Creature (1955), Quatermass II (1955), Quatermass and the Pit (1958-9), The Road (1963), about a haunting that may in fact be an example of time travel, The Year of the Sex Olympics (1968) about a future where the populace is pacified by televised sexual competitions, Wine of India (1970) about a future society that enforces euthanasia, The Stone Tape (1972) about the investigation of ghostly phenomena, the tv series Beasts (1976), Quatermass/The Quatermass Conclusion (1979), the comedy series Kinvig (1981) about an SF fans who has an encounter with aliens, and the ghost story tv movie The Woman in Black (1989). The Quatermass Xperiment/The Creeping Unknown (1955) was adapted from Kneale’s tv play without his involvement.

Trailer here