USA. 1958.

Crew

Director – Byron Haskin, Screenplay – Robert Blees & James Leicester, Based on the Novel From the Earth to the Moon (1865) by Jules Verne, Producer – Benedict Bogeaus, Photography – Edwin B. DuParr, Music – Louis Forbes, Special Effects Production Coordinator – Lee Zavitz, Special Camera Effects – Albert M. Simpson, Production Design – Hal Wilson Cox. Production Company – Waverly Productions.

Cast

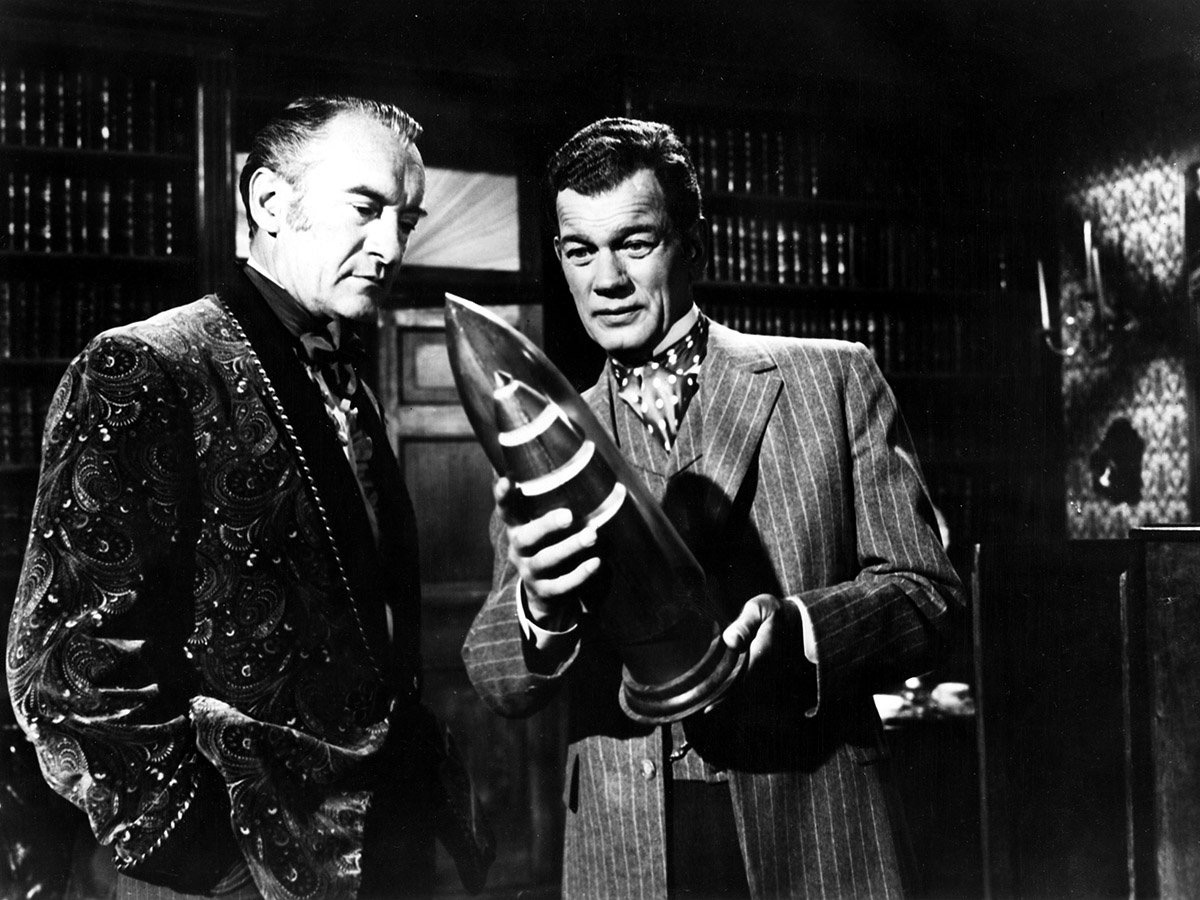

Joseph Cotten (Victor Barbicane), George Sanders (Stuyvesant Nicholl), Debra Paget (Virginia Nicholl), Don Dubbins (Ben Sharpe), Carl Esmond (Jules Verne)

Plot

Munitions manufacturer Victor Barbicane announces his discovery of Power X, the most powerful explosive ever devised. With the backing of other manufacturers, he plans to fire a projectile to the Moon as a demonstration. He is viciously denounced by Stuyvesant Nicholl, the manufacturer of an ultra-tough steel that Power X easily penetrates. Barbicane then receives a secret personal entreaty from President Ulysses S. Grant asking him to abandon the launch to stop other nations perceiving it as American warmongering. Vilified by his backers and the public for doing so, Barbicane comes up with a new scheme – to build a cannon that will fire a manned projectile to orbit The Moon. To this end, he recruits Nicholl’s aid, wanting his metal as a coating for the projectile, and asks Nicholl to join the expedition. However, once they successfully launch, Nicholl does everything he can to sabotage the expedition.

With the twin successes of Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) and MGM’s Around the World in 80 Days (1956), two lavish and popular works adapted from the works of Jules Verne, the doorway was opened for a fad for period Verne film adaptations. Soon screens were filled with the likes of The Fabulous World of Jules Verne (1958), Journey to the Center of the Earth (1959), Mysterious Island (1961), Master of the World (1961), Valley of the Dragons (1961), In Search of the Castaways (1962), Five Weeks in a Balloon (1962) and Jules Verne’s Rocket to the Moon/Those Fantastic Flying Fools (1967). Many of these efforts collapse into colourfully silly buffoonery but From the Earth to the Moon is notably one of the few serious entries in this late 1950s/early 60s spate of Jules Verne adaptations.

From the Earth to the Moon was directed by Byron Haskin who had earned a respectable number of genre stripes under George Pal with the likes of The War of the Worlds (1953), The Naked Jungle (1954) and Conquest of Space (1955), all of which demonstrated that Haskin had a good, if sometimes stolid, eye for Technicolor drama and special effects spectacle. From the Earth to the Moon has been reasonably lavishly produced – the interior of the spaceship rocket comes with beautifully plush interiors in the retro-Victorian style that became de rigeur for these Verne adaptations, as well as a series of Steampunk mechanical engine devices that one almost believes could work.

From the Earth to the Moon is nearly a good film. Almost, but not quite. It befalls the critical lack of nerve of most 1950s science-fiction films – that is they fall into self-absorption (with the end of the world, the threatening nature of the rest of the universe and The Bomb) and fail to take the imaginative leap out beyond the Earth to conquer the universe as seemed eminently within the imaginative grasp at the beginning of the decade with Destination Moon (1950). From the Earth to the Moon seems set to buck that trend and offers a grand leap into space, albeit one that has to look back to cod-Victorian science-fiction to find a sense of wonder about it. It builds up well through the battles and conciliations of the two rivals, played with fine charisma by Joseph Cotten and George Sanders. The rocket lifts off and then suddenly … nothing happens.

Just at the point we get into space and come to what promises to be the most interesting part of the story, the film slows right down and becomes a cabin drama about two rivals fighting one another. The dramatics are occasionally pumped up by a meteor shower and the emergency repair of an arcing engine gyro but in terms of the sense of wonder that From the Earth to the Moon could have held, these scenes are singularly unremarkable. There is almost nothing in the way of special effects shots – the rocket launch is limited to a series of exteriors of the capsule where the crane cable and arm holding it are clearly visible. Even the climactic Moon landing is allowed to take place off screen.

Moreover, Jules Verne’s story has been perverted by a need to add a topical theme about the nuclear arms race. In Verne’s original 1865 novel, the Baltimore Gun Club set themselves the challenge of building a rocket to go to the Moon; now club president Barbicane is an munitions industrialist and his scheme is that of firing a rocket to the Moon in order to demonstrate his powerful new explosive. The scheme does not make a great deal of sense and is where the film’s desire to add a comment on the arms debate leave us uncertain whether this is something that the film supports or condemns.

From the Earth to the Moon had previously appeared on screen uncreditedly when Georges Melies borrowed Verne’s idea of a projectile fired to The Moon from a cannon in A Trip to the Moon (1902).

Outside of his work for George Pal with The War of the Worlds (1953), The Naked Jungle (1954), Conquest of Space (1955) and The Power (1968), Byron Haskin also directed a number of other genre films including Tarzan’s Peril (1951), Captain Sindbad (1963) and Robinson Crusoe on Mars (1964), as well as episodes of the classic science-fiction anthology series The Outer Limits (1963-5).

Trailer here