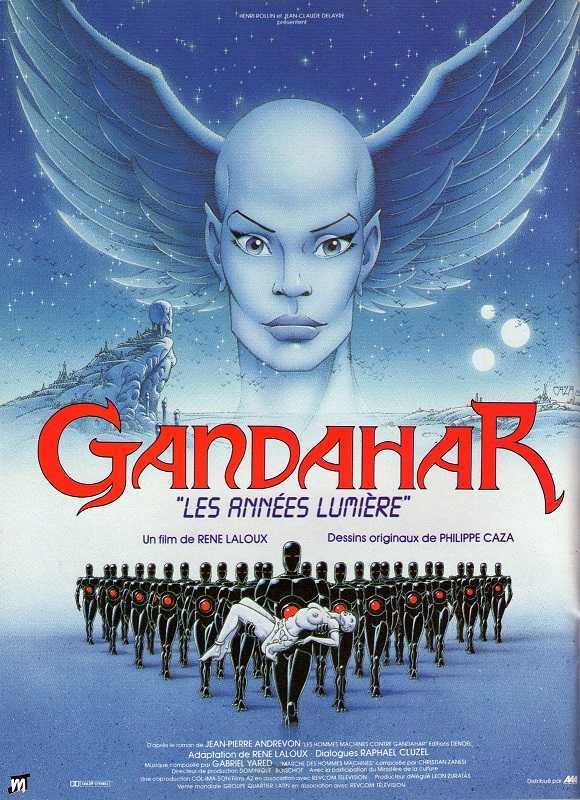

aka Light Years

France. 1988.

Crew

Director/Adaptation – Rene Laloux, Screenplay – Raphael Cluzel, Based on the Novel Metal Men Against Gandahar by Jean Pierre Androvan, Music – Gabriel Yared, Animation Design – Philippe Caza. Production Company – Col. Ima. Son/Films A2/Revcom Television/Centre National de la Cinematographie/Ministre de la Culture et de la Communication.

US Version – Light Years

Director – Harvey Weinstein, Adaptation – Isaac Asimov, Music – Bob Jewett, Jack Maeby & Gabriel Yared. Production Company – Miramax

Voices

John Shea (Sylvain), Jennifer Grey (Airelle), Christopher Plummer (Metamorphis), Glenn Close (Queen Ambisextra), Penn Jillette (Chief of the Deformed), Alexander Marshall (Apod), David Johansen (Shayol), Earl Hammond (Bleminhor), Charles Busch (Gemnen), Earl Hyman (Maxum/Chief of the Deformed), Teller (Octum), Terrence Mann (The Collective Voice of the Metal Men)

Plot

On the peaceful world of Gandahar, the Council of Women under Queen Ambisextra perceive a new and unknown threat to the world. The warrior Sylvain is sent forth to determine the nature of this threat. He encounters a race of invincible metal men who are making their way across the world, petrifying every person they encounter and then sending the bodies through a portal to return reprocessed into more metal men. Sylvain traces the source of the metal men to Metamorphis, a giant pink brain floating in the midst of the Circumventing Ocean. However, Metamorphis appears baffled as to how it could be the source of the metal men, even though all evidence indicates that it is. As the metal men make their way across the land, destroying the last defences of his people, Sylvain realises his only choice is to accept Metamorphis’s offer to be placed in a stasis capsule and awakened in one thousand years’ time so that he will be able to destroy Metemorphis’s weakened future self, which is the real source of the metal men.

Gandahar was the third and final feature film from French animator Rene Laloux (1929-2004). Laloux first emerged in the 1960s with surreal shorts such as Les Temps Morts (Dead Times) (1964) and Les Escargots (The Snails) (1965) and then had an acclaimed hit with the science-fiction film Fantastic Planet (1973). Laloux’s output subsequent to Fantastic Planet was sporadic – he only made one other film, The Time Masters (1982), a couple of shorts and nothing at all following Gandahar up until his death in 2004. Laloux’s films mark him one of the few animators in the world who makes films for grown-ups rather than children. He is someone who has embraced the spacey, mind-expanding look of adult illustrated fantasy – indeed, Laloux’s work embodies the essence of the French sf/fantasy illustrated magazine Metal Hurlant (1975-87).

Fantastic Planet was an amazing film. It has a conceptually way-out trippiness that came from the sheer bizarreness of the flora and fauna that Laloux packed in to the world he had created. Gandahar offers essentially the same. The film is filled with spinnily weird visuals – the under-race of The Deformed who come with multiple heads, arms protruding out of necks and stomachs or as walking torsos; a scene where the hero and heroine are drawn up into the bloodstream of a giant pink sea anemone; their being hatched from eggs and treated as the children of a dinosaur; and particularly the scenes with people trying to fight off the metal men using fighting crabs, pink hopping creatures that spew forth a forest of thorned trees, mouth creatures that devour the robots and so on.

Alas, the visuals here never feel as way out than they did in Fantastic Planet and more crucially the plot is tepid. There certainly seems to be much going for Gandahar as a film – bizarre mutants, spacey visuals, a genuine alienness and above all a plot that has a huge scope involving travel thousands of years into the future and a time paradox that entwines past, present and future along with predestined prophecy – but it all comes directed at a torpid pace that Laloux never fires up. The animation is also somewhat limited. A pity – this could have been an animated equivalent of a 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

In the US, the film was brought up by Miramax (which was then only a small company struggling to make it releasing indie films and not the major production company it is today), where it was re-edited and retitled Light Years. Miramax brought in Isaac Asimov to write an English-language script. Asimov was probably the world’s No.1 science-fiction writer at the time so it seemed a logical choice to employ him. However, the result seems a routine effort on Asimov’s part where he is clearly only a hired gun and has not put much effort into it. In fact, Gandahar‘s plot, which is more of an epic fantasy than it is a science-fiction film, seems almost the antithesis of Asimov’s writing, which dealt in hard science and the entirely explainable wonders of the universe, not in hallucinatory trips of the mind.

The credits of the American version are interesting to read – it is ‘presented by Isaac Asimov’ (clear evidence of the clout his name was seen to hold in the mid-80s science-fiction boom), while one can also see in the voice talents the names of Glenn Close, a then unknown Jennifer Grey and celebrity magicians Penn and Teller.

Although the most intriguing credit of all is that of the new director – none other than the later notorious Miramax CEO Harvey Weinstein, who has claimed director’s credit over and above Rene Laloux, even though he has not directed a single frame of animation anywhere in the film.

Trailer here

Full US version Light Years available online here:-