Crew

Director – Chris Hartwill, Screenplay – Sven Hughes & M. Smyth, Story – Sven Hughes, Producers – Simon Bosanquet & Mark Huffam, Photography – George Richmond, Music – Bill Grishaw, Visual Effects Supervisor – Stephen Coren, Visual Effects – Film Red, Additional Visual Effects – Mobius (Supervisor – Rodney J. McFal), Special Effects – Elements FX (Supervisor – Nick Morton), Prosthetics Designer – Clare Ramsey, Production Design – David Craig. Production Company – Generator Entertainment/Limelight/Northern Ireland Screen

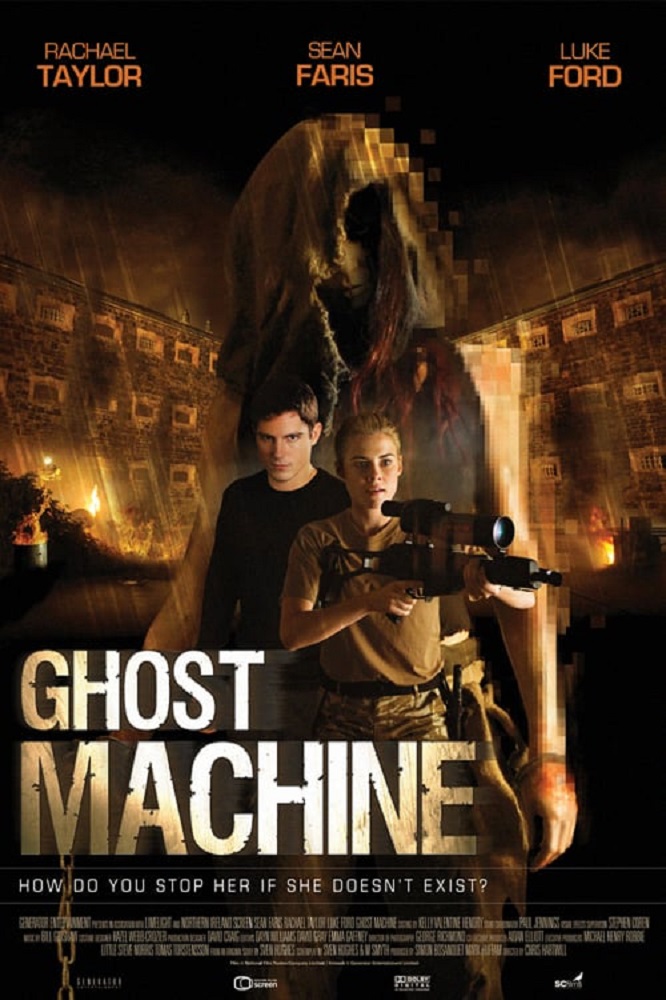

Cast

Sean Faris (Tom), Rachael Taylor (Jess), Luke Ford (Vic), Richard Dormer (Sergeant Taggart), Sam Corry (Iain Sullivan), Jonathan Harden (Benny), Hatla Williams (Prisoner K)

Plot

American software engineer Tom has developed a virtual reality combat simulator for use in training by the British military. His associate, the Australian Vic, is going out with the soldier Jess who is being bullied and sexually harassed by her superior officer Sergeant Taggart. Tom and Vic go away for the weekend, borrowing the work computers to set up a gaming simulation in a disused prison. Also joining them is their friend Benny and the building’s security guard Iain. However, once inside the game, they find that the virtual scenario has been invaded by the malevolent ghost of a woman who died during a rendition torture session conduced in the prison and is now warping the simulation to keep them trapped inside.

Ghost Machine is a principally Irish-made and shot film. It did the rounds of several fantastic film festivals but received little in the ways of good reviews. The creative talents were all newcomers and have failed to go onto anything since then.

Ghost Machine feels exactly like a film that was made between the points of The Lawnmower Man (1992) and The Matrix (1999) – a brief period that was filled with mostly cheap imitators such as Arcade (1994), Brainscan (1994), Virtual Combat (1995), Virtuosity (1995), Revelation (1999) and The Thirteenth Floor (1999) and in particular the near similarly titled Ghost in the Machine (1993), which likewise had a vengeful killer being incarnated in cyberspace.

Up until The Matrix, the Virtual Reality film existed in a B movie ghetto that ill-informedly exploited the public’s fascination/fears with the new paradigm of the internet and cyberspace and wedded these to the CGI-generated vistas that had been opened up by The Lawnmower Man. Most of the films from this period gave the impression that the creative talents involved had spent little if any time tinkering with computers or even having put on a VR helmet. They frequently construed Virtual Reality as either an all-immersive realm, subject to real-world physics (where heroes and villains could have fistfights and physically vanquish the other with a display of force/strength) or that the simulation would be so perfect that the virtual realm was unidentifiable from the real world.

As the future nearly twenty years on has shown, almost all prognostications of Virtual Reality (even those put forward by its guru William Gibson) have never come to pass – Second Life never quite took off and the only people interested in even semi-immersive worlds are those in MMORPGs like World of Warcraft, while the majority of people seems more interested in using the web to engage in expanded versions of real-life functions such as library search, to read newspapers, enjoy various media and in particular socialising.

Ghost Machine follows all of these cliches as though nothing had changed since 1995. The virtual realm is a perfect simulation of the real world – with great economy this is a disused jail location in Belfast that the filmmakers obtained the use of (allowing the virtual world to be represented by cut-price location shooting without the need to create any expensive Lawnmower Man-styled virtual effects). Characters are able to feel blows and torture inflicted on their bodies inside the simulation. There is also the absurd point near the climax where the characters are running to get to ‘the extraction point’ in order to physically exit the simulation – you keep wondering why the players don’t just simply remove their VR helmets.

There is another ridiculous piece about the evil force inside the simulation being able to rearrange the architecture and trap someone inside a room, leaving a wall in its place – and that the person so trapped is unable to be found even though the people searching for them are sitting right beside the player on a couch in the real world. Even funnier is when the film centres around the idea of the evil force only being able to be defeated by a laser gun that has been created virtually inside the game.

When the film gets to the use of a program entitled Create Your Sex Fantasy that allows someone to design their perfect virtual woman, you sink in your seat as Ghost Machine seems to be heading in the direction of a number of bad virtual sex fantasies such as Virtual Seduction (1995), Cyberella: Forbidden Passions (1996), Virtual Encounters (1996), Game of Pleasure (1998) and Virtual Girl (1998). There are also all the cliches at the end about the players exiting the simulation into the real world only to find they haven’t exited at all whereupon everything deteriorates into a series of ridiculous rubber reality games where you cease to find anything that happens thereafter believable.

Like Ghost in the Machine, Ghost Machine has been crosshatched with a horror theme about the spirit of a woman murdered in the jail who somehow manages to incarnate inside cyberspace. In terms of horror, director Chris Hartwill generates nothing that is in anyway remotely scary or intensive. The film feels entirely like a series of processed shocks and action scenes that have been regurgitated from elsewhere without feeling. Much of the early lead-up to the film seems to involve a canned score trying to generate sinister effect where none exists from the directorial hand. The film does have an interesting political undertow in that the evil presence that infects the game is the soul of a woman killed during a War on Terror rendition session – alas, the film does nothing with this. Indeed, in its personification of the victims murdered by CIA rendition as a force of evil, what initially appears to be a potent political undertow to the film surely ends up only bolstering the establishment viewpoint.

Trailer here