USA. 1971.

Crew

Director – Jim McBride, Screenplay – Lorenzo Mans, Jim McBride & Rudolph Wurlitzer, Photography – Alan Raymond, Art Direction – Gary Weist. Production Company – Universal Marion Corporation.

Cast

Steven Curry (Glen), Shelley Plimpton (Randa), Woodrow Chambliss (Sidney Miller), Garry Goodrow (Magician)

Plot

It is a number of years after civilisation has collapsed. Glen and Randa are two young people in a small community of survivors. They puzzle over various artifacts they find. A travelling magician visits the community and amazes everybody with his display of electrical appliances. Glen is determined to visit the city and the magician gives him directions how to get there. He and the pregnant Randa set out on a journey through the wilderness.

From the 1980s onwards, the post-apocalyptic venue has become a cliche – one filled with mohawked crazies burning up the last fuel supplies in kamikaze death races, small communities trying to maintain civilised order against the barbarian onslaught and brokedown cyborgs looking for their purpose. Before 1981 and Mad Max 2 (1981), the post-holocaust film was very different. The first works in this vein such as Five (1951), Day the World Ended (1955), The World, The Flesh and The Devil (1958), On the Beach (1959) and Panic in Year Zero (1962) were ones that concerned themselves with the questions of survival in the immediate aftermath and particularly with the survivors all getting along together. (For a more detailed overview of the genre see After the Holocaust Films).

There was another spate of post-holocaust films that came in the 1970s in the midst of the Love Generation. These included works like Roger Corman’s satirical Gas; or It Became Necessary to Destroy the World in Order to Save It (1970), Glen and Randa here, Idaho Transfer (1973) and even The Omega Man (1971). In these, it was seen that the Flower Children would be the ones who would inherit civilisation and that maybe with the corrupt virtues of society torn down their freedom and innocence might make for a better world.

On the other hand, all of these films with the exception of The Omega Man seemed pessimistic about this ever happening – Gas-s-s saw the Youth Generation immediately becoming the new conservatives, Idaho Transfer held out bleak hopes for the survival, while Glen and Randa has the two love children setting out on a quest for civilisation but never getting there and even worse in Logan’s Run (1976) the youth find the world is theirs but immediately abandon the hedonistic lifestyle and discovers the joys of getting old. There is the overriding sense in these that having inherited the Earth, the Flower Children wouldn’t know what to do with it anyway.

Glen and Randa has a mixed reputation among genre commentators. A large part of the criticism levelled against it is that it is meandering and lacks a clear plot. I can’t say these were particularly issues that I had a problem with for it is a film made up of oblique observations, of seeing the two innocents and the way they interpret facets of the civilisation that are familiar to us. In these respects, Glen and Randa is actually very good science-fiction in that it is about viewing the everyday and familiar through eyes to whom it is alien.

In the opening scene, we meet the naked Glen (Steven Curry) and Randa (Shelley Plimpton) as they drift through the woods and find a car halfway up a tree. Curry gets in and mimics driving it, while wondering “Maybe it’s a car becoming a tree?” In the next scene, he finds a piece of junk and they speculate over what is written on it “Made in USA (pronounced ‘Ooo-sa’) – maybe that’s where they went?” The nakedness of the two characters leads to inevitable Edenic allegories, as the film is really one about how two innocent and unworldwise people perceive the world.

In the next scenes, we encounter the rest of the small community scavenging and see old refrigerators having been converted into carts and signs advertising Food and Fuel lying abandoned. Here we get the clear sense that civilisation and all its trappings have now become meaningless. There are constant throwaway pieces of dialogue that create a fascinating sense of people living in ignorance of civilisation – they encounter a horse and Shelley Plimpton fearfully worries “It only wants to eat us like the rest of the dogs,” or where Steven Curry fails to understand when Woodrow Chambliss talks about a concept like “twenty minutes.” In the latter scenes, we see Steven Curry trying to maintain the mimicry of a middle-class lifestyle – sitting on a couch watching a dead tv with a pipe in his mouth and then picking up a dead telephone to yell “buy Xerox” into it.

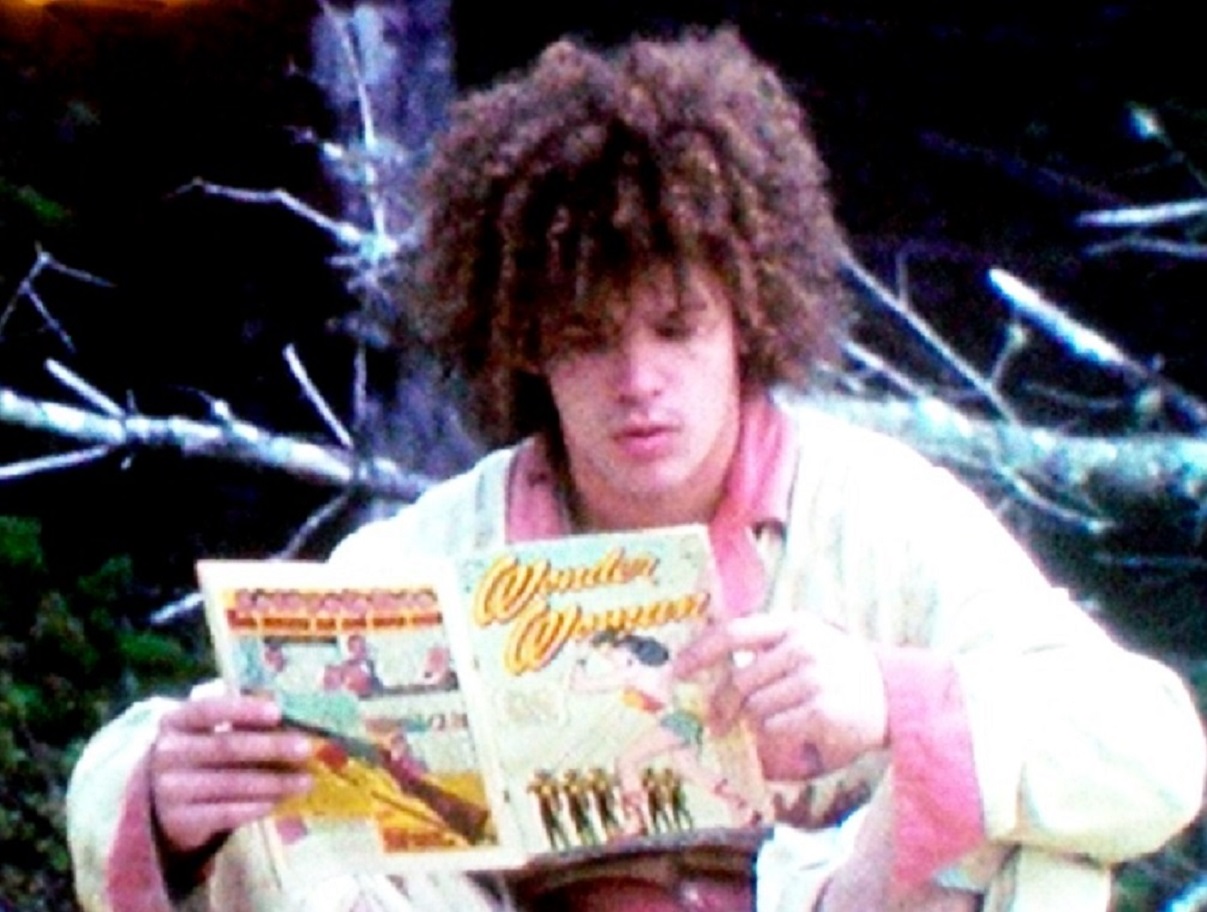

The most fascinating character is that of Garry Goddrow’s magician who wows the community with what to us are simple gadgets and electrical devices – fireworks, electric blenders, lightbulbs and lamps – and we see that the display of technology has now become something akin to magic (the old Arthur C. Clarke adage). We also see Steven Curry discovering an old Wonder Woman comic-book and construing it as a new mythology, telling Shelley Plimpton stories from it when she falls ill as though they were bedtime stories, saying “shazam” when lightning bolts flash and stating that the city they are searching for is Metropolis. In this, we see that the film is doing something utterly fascinating with the post-holocaust idea – construing the past (our present) the way people of a pre-civilised society would see it.

The film has a meandering plot, even at time leaves you questioning if it has any clear direction. It reminds more of a Terence Malick film like Badlands (1973) or Days of Heaven (1978) about innocents drifting through an exquisite paradise-like landscape. However, it is the fascinating images of people comprehending the detritus of contemporary civilisation that makes Glen and Randa fascinating viewing. The film was made on a grant from the American Film Institute and you suspect that the reason they never reach Metropolis is simply that recreating a dead city would have been beyond the scope of the film’s budget.

Glen and Randa was the first fiction film of Jim McBride. He subsequently went onto make the sex comedy Hot Times (1974), the Richard Gere remake of Breathless (1983), to direct Dennis Quaid in The Big Easy (1987) and Great Balls of Fire (1989), and a couple of other minor films as well as various tv work. His only other genre works are the tv movies Blood Ties (1991), a vampire film, and Dead By Midnight (1997) about a cyborg. Steven Curry and Shelley Plimpton have appeared in only a handful of other roles – Shelley Plimpton is best known as the mother of actress Martha Plimpton, indeed had just given birth to her before Glen and Randa was released.

Trailer here