USA/UK. 2005.

Crew

Director – Garth Jennings, Screenplay – Douglas Adams & Karey Kirkpatrick, Based on the Novel and Radio Series The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams, Producers – Gary Barber, Roger Birnbaum, Jonathan Glickman, Nick Goldsmith & Jay Roach, Photography – Igor Jardue-Lillo, Music – Joby Talbot, Visual Effects Supervisor – Angus Bickerton, Visual Effects – Cinesite (Europe) Ltd (Supervisors – Matt Johnson, Adam McInnes & Sue Rowe), Models – Asylum Models and Effects Ltd, Animated Guide – Shynola, Knitting Sequence – Sean P. Marthiesen, Special Effects – Special FX (UK) Ltd (Supervisor – Paul Dunn), Creature Effects – Jim Henson Creature Shop (Supervisor – Jamie Courtier), Production Design – Joel Collins. Production Company – Barber-Birnbaum/Hammer and Tongs Productions/Everyman Pictures

Cast

Martin Freeman (Arthur Dent), Sam Rockwell (Zaphod Beeblebrox), Zooey Deschanel (Trisha ‘Trillian’ McMillan), Mos Def (Ford Prefect), Bill Nighy (Slartibartfast), Stephen Fry (Voice of The Book), Warwick Davis (Marvin), Alan Rickman (Voice of Marvin), John Malkovich (Humma Kavula), Anna Chancellor (Questular), Richard Griffiths (Voice of Vogon Prostetnic Jeltz), Helen Mirren (Voice of Deep Thought), Steve Pemberton (Prosser)

Plot

Arthur Dent wakes up one morning to find workmen outside his door come to demolish his house to make way for a bypass. He lies in front of the bulldozer to prevent this but is interrupted by his best friend Ford Prefect who informs Arthur that he, Ford, is in fact from the planet Betelgeuse and that the Earth is about to be demolished in 12 minutes. Moments later, a fleet of ships manned by the obstreperous Vogons appear and proceed to blow the Earth up to make way for a hyperspace bypass. However, Ford manages to beam himself and Arthur aboard the Vogon ship. Once there though, they are captured, forced to listen to the captain’s ghastly poetry and then thrown out of the airlock. They are saved by the spaceship Heart of Gold, which is powered by the new Infinite Improbability Drive and has been stolen by Ford’s part-brother Zaphod Beeblebrox, the two-headed, three-armed President of the Galaxy. Also with Zaphod is a human girl Trisha ‘Trillian’ McMillan, who Arthur once met at a party and fell in love with, only to see her swept away by Zaphod. Arthur and Ford join Zaphod’s quest to find the lost planet Magrathea. Their journey is interrupted by pursuing Vogons come to arrest Zaphod for kidnapping himself, and Zaphod’s Presidential rival, the cult leader Humma Kavula.

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is a film spun out from the ‘creation’ of Douglas Adams. It is hard to state exactly what the The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy phenomenon is as it has existed in so many different mediums that it has become more like a creative entity that exists beyond being able to be pinned down as any one single book or series. The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy first appeared as a BBC radio show that aired in two 6-part series in 1978 and 1980. Douglas Adams then turned his scripts into two novels, The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1979) and The Restaurant at the End of the Universe (1980). The books and radio series were later expanded into a six-part BBC tv series The Hitch Hikers Guide to the Galaxy (1981). Around this time, The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy became a cult phenomenon and soon after Douglas Adams began marketing it in every conceivable way. There were three mediocre book sequels – Life, the Universe and Everything (1982), So Long and Thanks for All the Fish (1984) and Mostly Harmless (1992), along with The Salmon of Doubt (2001), a work that was released uncompleted following Adams’s death and may or may not have been material for a further Hitch Hiker’s book; the radio series was re-edited and released as a set of LPs; there was a play that first appeared in 1979; a text computer game version that was released by Infocom in 1984; the original radio scripts were released in print editions; there was a comic book; a wiki website h2g2.com; a third BBC radio series adapting adapted Life, the Universe and Everything (2004); and all manner of merchandising items including T-shirts, badges and even printed towels. However, as the weak works that he published elsewhere – the Dirk Gently novels, The Meaning of Liff (1983) – demonstrated, Douglas Adams seemed to be the case of a writer who has one good idea in his life and spent the rest of the time trying to milk it for all he could.

Certainly, Douglas Adams’ one creation was frequently side-splitting – the best versions of The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy are generally regarded as being the radio series and the first two books – where Adams brought the cruel and absurdist British wit as patented by The Goon Show and Monty Python’s to bear on various science-fiction clichés. The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy was a grand science-fictional creation that sits well alongside the cruel and absurd universes that feature in the works of writers like Kurt Vonnegut Jr, John Sladek and Robert Sheckley. Adams wittily spoofed a number of science-fiction conventions – artificial intelligence, the End of the World, hyperspatial travel, clichés of encounters with aliens where people invariably speak English – all with an irreverent dash of Philosophy 101. Many aspects of the series have gone on to become classics – the joke about the Question to the Meaning of Life; Marvin the doleful android; the Babel Fish; the Infinite Improbability Drive. Indeed, during this author’s university years, it became difficult to attend certain parties without being assailed by someone who would block quote various sections of The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

Douglas Adams worked on the screenplay for a film adaptation of The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy for a number of years. The production was first announced as long ago as 1982 and it has passed through various directional hands, including those of Ivan Reitman, Spike Jonze and Jay Roach. Sadly, Douglas Adams died in 2001 before the project ever went to cameras. Though he delivered initial drafts for the film, the screenplay was rewritten by Karey Kirkpatrick. Karey Kirkpatrick has a number of genre credits to his name, ranging from the quite good – James and the Giant Peach (1996) and Chicken Run (2000) – to forgettable children’s fodder like The Rescuers Down Under (1990), Honey, We Shrunk Ourselves (1997), The Little Vampire (2000), Charlotte’s Web (2006), The Spiderwick Chronicles (2008), The Smurfs 2 (2013) and Chicken Run: Dawn of the Nugget (2023), while he also directed Over the Hedge (2006), Imagine That (2009) and the animated Smallfoot (2018). The director eventually assigned to the film was Garth Jennings, who had previously made MTV clips for artists like REM, Blur, Pulp and Supergrass, with The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy being his feature film debut.

The film made a big thing out of maintaining that most of the changes had been made or approved by Douglas Adams himself. With Adams no longer being around to confirm this, these claims should be taken with a pinch of salt. You are not entirely sure if the film is being boastful in its claim to be blessed by Douglas Adams or (more likely) that Adams did make the changes but Karey Kirkpatrick went back and rewrote the material. It is certainly hard to believe that Adams directly wrote any of the fresh material that appears on screen – the new patches of dialogue and Guide excerpts are singularly lacking in the dry Douglas Adams wit.

Certainly, the film touches bases with many aspects of the original – there is a Hitch Hiker’s Guide, Babel Fish, Vogon Poetry, Slartibartfast and his Norwegian fjords, Deep Thought, the white mice, even the whale and bowl of petunias – but it feels more like one is sitting through a Reader’s Digest Condensed Version of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Maybe it can be best compared to trying to dance to a live band doing a cover of a favourite song where one keeps expecting the rendition to hit certain beats in the music, only to find they have been miscued slightly. There is the scene at the start where Arthur Dent lies in front of the bulldozer and Ford Prefect turns up to tells him the Earth is about to end in twelve minutes but you are left waiting for the next part of the gag where Arthur persuades Prosser to lie down in his place; there is the explanation from the Guide of how the Babel Fish is one of the most peculiar creations in the universe but what is missing from the gag is the hilarious little bit about the Babel Fish’s existence causing God to disappear in a puff of logic (perhaps edited out so as not to offend the Religious Right); there is the speech about how space is really, really big but instead of going through the whole thing it fades off with Stephen Fry’s voice of The Book saying “and so on”.

In other scenes, what is going on must be confusing to any audience member not familiar with the originals – there is no explanation about why it is necessary to drink so much beer before teleporting; nothing about how Marvin has been chosen with a depressed Genuine People Personality; no explanation of the necessity of towels, which must surely leave audiences wondering why Ford Prefect is maniacally waving them at the Vogons throughout. And almost certainly American audiences would not get the joke about Ford Prefect’s name – that it is in fact the name of a small British car produced in the 1940s and 50s – and the film plays it in straight-face, seemingly as though unaware of the joke.

Much of the humour is furthermore killed by director Garth Jennings. As opposed to Douglas Adams’s dryly absurdist wit, Jennings more often than not pitches the show down at a slapstick level – custard pie sequences with people being slapped in the face by devices on Vogsphere, fighting over who is driving the pod, using the empathy gun on each other and so on. While Douglas Adams had me laughing myself silly the first time I read the books, the film barely raises a smile. Maybe it is simply that the multiple versions of the story and endless fan quotings of sections has inured one to the newness of the jokes, but I don’t think so. Certainly, the audience I saw The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy film with barely laughed throughout.

With Touchstone (Disney) as its distributor, this is also a The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy that has been retooled for the American market. The essential Britishness of the original has been watered down – the roles of Zaphod Beeblebrox, Ford Prefect and most noticeably Trillian have all been cast with American actors. Moreover, many elements have been amplified to make the film a much easier sell with the Mid-American box-office demographic – an unrequited romance between Arthur and Trillian has been invented specifically for the film; the Vogons have had their presence in the story amplified so that they can become the heavies; and there is a sentimentalism that underlies it all – Arthur just wants to find true love with Trillian and, like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz (1939), to go back home again.

The problem with the books and radio and tv series is that Douglas Adams never seemed that interested in plot, more in writing gags and sardonic asides. This can clearly be evidenced in the way that with the various incarnations of The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Adams was able to shuffle aspects of the story around in a different order without it seeming to make much overall difference. His other works – most notably the Dirk Gently books – often seemed like first drafts of ideas that needed someone to come and work them into a unifying or even coherent plot. The film is stuck with the ungainly task of having to take a series of extended gags and weave the formula of an A-budget movie around them. Thus we get extended pieces of additional plotting for the purpose of giving the film some drive – the visit to Vogsphere in order to rescue Trillian from the Ravenous Bugblatter Beast, the encounter with John Malkovich’s Humma Kavula in order to provide the story with something vaguely like a villain.

The film has made a virtue of trying to quote and pay tribute to the source – the Marvin from the BBC series turns up in several shots in the background of the Vogon bureaucratic office; Simon Jones, the original Arthur Dent, has a cameo as the recorded Magrathean hologram greeting; while Douglas Adams’s nose was apparently made into a model for one of the planets in the background of the Magrathean workshop floor; and a reworked version of The Eagles’ Flight of the Sorcerer, the theme music from the tv series, appears part way into the film. However, the question that nobody seemed to have asked is who the filmmakers were selling the film to. It is difficult to believe that many new fans will convert to the books/series etc because of the film – there are so few times that the screen lights up with any of the absurdist wit that flows through the other incarnations of The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy – so that leaves hardcore Douglas Adams fans, who can only come out of the film disappointed.

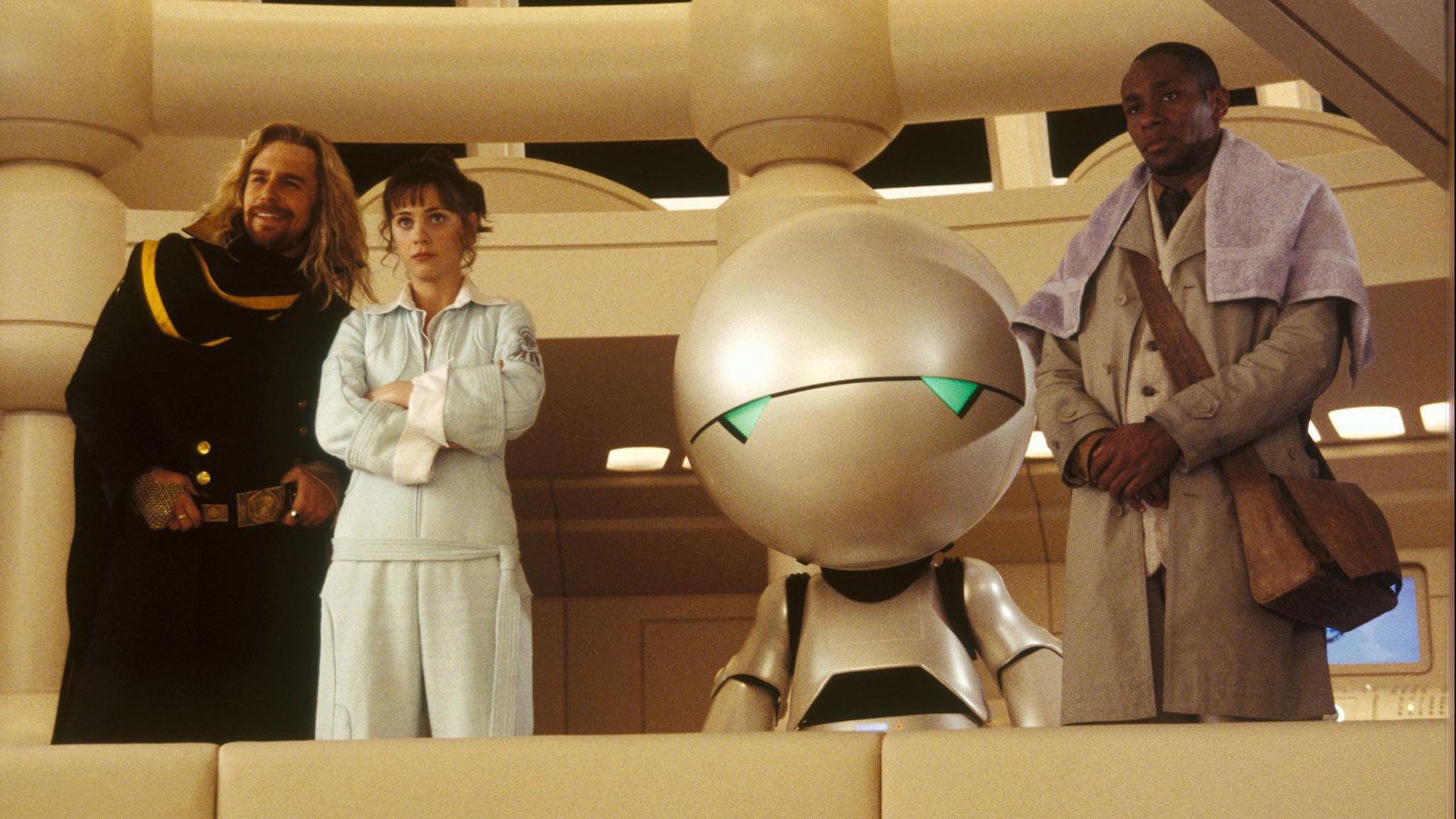

Martin Freeman makes a merely adequate Arthur Dent. As Trillian tells him at one point: “Arthur, get a backbone.” This unwittingly does put a finger on the pulse of Martin Freeman’s performance – certainly, he pales in comparison to the blithe twittishness of Simon Jones’s performance in the tv series. Sam Rockwell plays over-the-top – when the second head appears, he for all the world seems to be channelling Robin Williams – but at least this is exactly what the character of Zaphod Beeblebrox is meant to be. The casting of Mos Def, an African-American hip-hop artist, as Ford Prefect was a controversial decision with fans – certainly, Mos Def never embarrasses himself but then Ford has become a relatively minor background character in the film. The best performances in the film are in fact the voice actors where Alan Rickman and Stephen Fry do a spot-on job of recapturing the tones of Stephen Moore and the late Peter Jones who voiced respectively Marvin and The Book in the original radio and tv series’.

The tv series certainly felt like it was faithful to Douglas Adams a whole lot more than this film, even if it was beset by cheap BBC production values. The one thing that the film has going for it is an A-budget and some fine sets and effects. The film takes full opportunity to visually approximate Adams with some impressive spaceships, Vogon nasties, journeys through the Magrathean workshop floor and the reconstruction of Earth and so forth. The two improvements the film makes over the series is a much better designed Marvin and actually allowing Zaphod Beeblebrox to have two heads (although like the tv series, it cheats in its own way and only occasionally has Zaphod’s other head and arm pop up from in hiding). Ultimately, there is the feeling that Douglas Adams’s wit never needed these things. Impressive and all as the production values of the film are, one wishes the creativity would have gone in the other direction – like hiring a director with a better feel for the material or simply adhering to the source with greater finesse.

The only other Douglas Adams adaptations we have had to date has been the short-lived tv series based on his holistic detective Dirk Gently (2010-2), although only five episodes were ever made of this, although the subsequent tv series Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Ageny (2016-7) was a far more successful endeavour. Adams also worked as script editor for one season of the original Doctor Who (1963-89) and wrote two of its stories.

Garth Jennings subsequently went on to make the comedy Son of Rambow (2007) and the reasonable success of the animated Sing (2016) and its sequel Sing 2 (2021).

(Nominee for Best Production Design at this site’s Best of 2005 Awards).

Trailer here