USA. 1957.

Crew

Director – Jack Arnold, Screenplay – Richard Matheson, Based on his Novel The Shrinking Man, Producer – Albert Zugsmith, Photography (b&w) – Ellis W. Carter, Music – Fred Carling & E. Lawrence, Special Effects – Everett H. Broussard, Roswell A. Hoffman & Clifford Stine, Makeup – Bud Westmore, Production Design – Robert Chatsworthy & Alexander Golitzen. Production Company – Universal-International.

Cast

Grant Williams (Scott Carey), Randy Stuart (Louise Carey), April Kent (Clarice Bruce), William Schallert (Dr Arthur Bramson), Paul Langton (Charlie Carey)

Plot

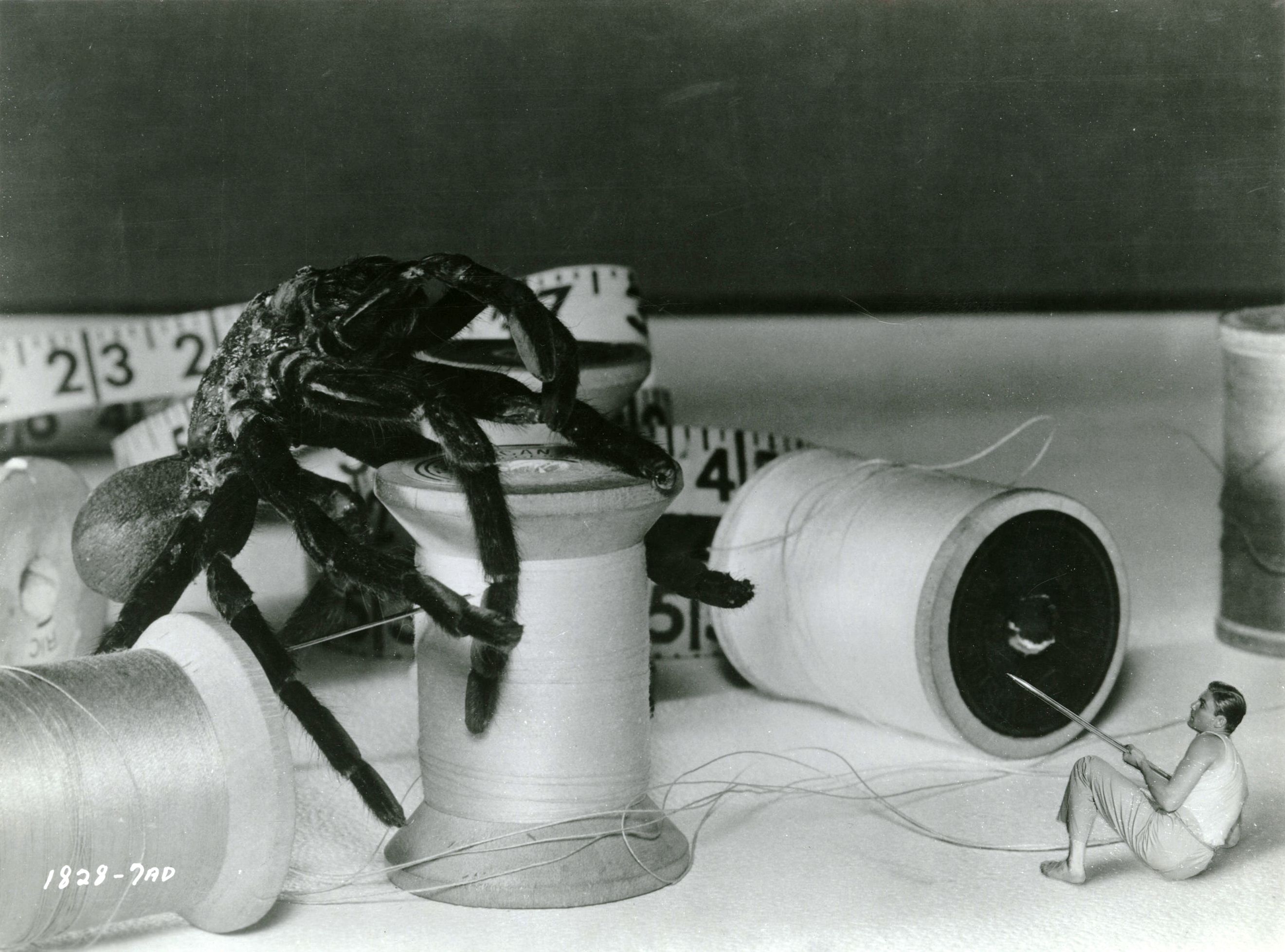

While on holiday at sea, Scott Carey is enveloped in a glowing cloud. Upon returning home, he finds that he no longer fits his clothing and is losing weight and height. Medical tests show that radiation from the cloud is reacting with an insecticide on his skin and is causing him to progressively shrink. He loses his job and has to sell his story to the media to pay the bills, which leaves him surrounded by curiosity seekers. His relationship with his wife deteriorates. He finds acceptance with a female circus midget for a time but leaves when he becomes smaller than her. Reaching only six inches tall, he makes his home in a doll’s house from where he tyrannically domineers his wife. He is then attacked by a cat and falls down into the cellar. At his size, this becomes a world of frightening proportions in which he has to survive giant-sized spiders, mousetraps and ruptured boilers.

The Incredible Shrinking Man is one of the classics from the Golden Age of Science-Fiction and would have to be my personal second favourite of all 1950s science-fiction films – with Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) taking the No. 1 spot. There have been other miniature-sized adventure films before – most notably Dr Cyclops (1940) and the later likes of tv’s Land of the Giants (1968-70) and Honey, I Shrunk the Kids (1989). However, The Incredible Shrinking Man has a greatness and stature that stands it head and shoulders above (or perhaps considering the theme, below) the others.

The Incredible Shrinking Man was directed by Jack Arnold (1916-1992). Jack Arnold was the most celebrated of directors within the science-fiction genre in the 1950s. Arnold first appeared with the eerily haunting It Came from Outer Space (1953), one of the first films to delve into the 1950s alien body snatcher theme. All of Jack Arnold’s films seem run through with metaphors and images about mankind suddenly becoming a stranger inside his environment – the sheer alienness of the desert terrain in the likes of It Came from Outer Space and Tarantula (1955), or the stygian depths of the Amazonian jungle lurking with prehistoric menace in The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954).

Over these films looms a sense of the vastness of geological time, of the world being something so expansive that it leaves humankind akin to an ant on the surface of a beach. The Incredible Shrinking Man, which does literally cast one man as an alien inside his own home environment, is Jack Arnold’s single greatest masterpiece. (See below for a listing of Jack Arnold’s other films).

The cellar survival scenes that take up the last third of the film are Jack Arnold’s greatest half-hour. The scenes are virtually silent with barely half-a-dozen lines of dialogue. There is something fascinating to seeing the familiar turned into an alien world – how the journey across a giant-sized can of paint is turned into something intensely suspenseful, or the seat-edge peril of the pursuit by the cat. The effects, sets and process work during these scenes are exemplary.

The rest of the film is filled with startling reversals and depth perspective shots on Jack Arnold’s part – there is one particularly fine shot where we see Grant Williams’s wife and brother talking while the camera is focused over the back of an armchair in centre frame and we then cut to the chair and see the tiny Williams sitting on it for the first time to some considerable shock. Grant Williams’s slight blankness of playing only adds to the melancholy of Carey’s plight.

Unlike the abovementioned films, The Incredible Shrinking Man has a subtext that is so much more than a standard miniature-sized adventure story. Grant Williams’ journey down to micro-size is not merely a physical but a psychological journey. The film takes on a supplementary thesis exploring power and domination. One can even read The Incredible Shrinking Man as an early feminist fable (before such ideas ever entered mainstream intellectual discourse) – how man’s esteem and abuse of power is related to his ability (or inability) to physically dominate his environment. The smaller Grant Williams gets, the more tyrannically he dominates his wife – he flees her into the arms of April Kent’s midget but then abandons her when he shrinks to the point where she becomes taller than him.

The ending, wherein Grant Williams disappears down to atomic-size saying that with God there is no zero, has a grandiose portentousness that only 1950s science-fiction would dare. Perhaps it is the one moment in 1950s science-fiction that holds the apotheosis of the Atomic Age’s great existential dilemma. Other films of the era seem bowed under fear of the thinly veiled threat of the Communist menace or of anxiety about the atomic bomb being unleashed. In most of these films, there was the nervous trust in the authorities, the belief that the military and scientists would know what to do. Other films such as Red Planet Mars (1952) and The War of the Worlds (1953) turned to seek solace in religion and belief that the Almighty would save us.

The Incredible Shrinking Man was the first film to bare that anxiety open. It symbolically plunges down to the infinitesimal where man vanishes to become nothing at all. At the same time, the moment of vanishing becomes a great cry of self-assertion, an existential throwing of oneself into the vastness of the infinite and the hope that its limitlessness will provide. It is a moment of both extraordinary nihilism and extraordinary poetic grandeur and hope. In the decade to come, science-fiction would constantly reach towards the infinite in films like 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Right here is that first moment where American science-fiction cinema began to reach out toward the enormous transcendental ache that is part of science-fiction’s ongoing conceptual quest.

For a time afterwards, writer Richard Matheson purportedly worked on a sequel entitled The Incredible Shrinking Girl, but this never emerged. The film was remade as The Incredible Shrinking Woman (1981), an explicitly comedic remake with Lily Tomlin, which is not unenjoyable in its own right. A comedy remake has been announced for the 2010s starring Eddie Murphy. The success of The Incredible Shrinking Man was quickly followed by a spate of big and small people films, including the likes of The Amazing Colossal Man (1957), Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958), Attack of the Puppet People (1958), Giant from the Unknown (1958), The 30-Foot Bride of Candy Rock (1959) and The Temptation of Dr Antonio (1962), as well as the short-lived tv series World of Giants (1959), which reused the giant-sized sets from The Incredible Shrinking Man and featured Marshall Thompson as a miniaturised spy.

Jack Arnold’s other genre films are:– It Came from Outer Space (1953), The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), Revenge of the Creature (1955), Tarantula (1955), Monster on the Campus (1958), The Space Children (1958), The Mouse That Roared (1959) and Hello Down There (1969), as well as the story for The Monolith Monsters (1957).

The Incredible Shrinking Man was the screen debut of legendary writer Richard Matheson (1926-2003). Matheson adapted the script from his second novel The Shrinking Man (1956). He sold the film rights to the book on the sole agreement that he could write the screenplay. When The Incredible Shrinking Man proved a breakthrough success, Matheson began selling to tv’s The Twilight Zone (1959-63). Matheson went onto produce an extraordinary body of genre work. His other genre scripts are:– Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe adaptations The House of Usher/The Fall of the House of Usher (1960), Pit and the Pendulum (1961), Tales of Terror (1962) and The Raven (1963), the Jules Verne adaptation Master of the World (1961), the occult film Night of the Eagle/Burn, Witch, Burn (1961), the Corman-produced mortician’s comedy The Comedy of Terrors (1963), The Last Man on Earth (1964) based on his novel I Am Legend (1954), the Hammer psycho-thriller The Fanatic/Die, Die, My Darling (1965), the classic Hammer occult film The Devil Rides Out/The Devil’s Bride (1968), the historical biopic De Sade (1969), Steven Spielberg’s first film Duel (1971), The Night Stalker (1972) and The Night Strangler (1973) tv movies, the haunted house film The Legend of Hell House (1973), the tv adaptation of Dracula (1974), the tv movies Scream of the Wolf (1974), The Stranger Within (1974), Trilogy of Terror (1975), Dead of Night (1977) and The Strange Possession of Mrs. Oliver (1977), the tv adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles (1980), the time travel romance Somewhere in Time (1980) from his own novel, Jaws 3-D (1983), Twilight Zone – The Movie (1983), and numerous classic episodes of The Twilight Zone, Thriller and Star Trek. Works based on his novels and stories are The Omega Man (1971) from his I Am Legend, the afterlife fantasy What Dreams May Come (1998), the fine ghost story Stir of Echoes (1999), I Am Legend (2007), The Box (2009) and Real Steel (2011).

Trailer here