USA. 1956.

Crew

Director – Donald Siegel, Screenplay – Daniel Mainwaring, Based on the Novel The Body Snatchers by Jack Finney, Producer – Walter Wanger, Photography (b&w) – Ellsworth Fredericks, Music – Carmen Dragon, Special Effects – Milt Rice, Makeup – Emile LaVigne, Production Design – Edward Haworth. Production Company – Allied Artists.

Cast

Kevin McCarthy (Dr Miles Bennell), Dana Wynter (Becky Driscoll), King Donovan (Jack Belicec), Carolyn Jones (Theodora Belicec), Larry Gates (Dr Daniel Kaufman)

Plot

Miles Bennell, a GP in the small Californian town of Santa Mira, returns from an out-of-town meeting to find himself inundated with calls from locals insisting that members of their family are not the same people any more or have changed in some way. Believing this to be some type of mass hallucination, he refers them to a psychiatrist. He meets his old girlfriend Becky Driscoll and starts seeing her again. They are interrupted at dinner by mystery writer Jack Belicec who takes them to see a body found on his pool table, one mysteriously lacking any type of distinguishing marks, even fingerprints. As Jack sleeps, his wife sees the body form into a likeness of Jack, even down to a recent cut on its hand. Miles finds a similar body forming in Becky’s basement. However, when they call the police, the bodies have vanished and they think in the rationale of daylight that they have succumbed to the mass delusion too. As night falls again, they find pods in Miles’s glasshouse. When they try to run they find that the townspeople everywhere have turned into hostile, emotionless pod people trying to stop them.

This brilliant, terrifying film was the best thing the science-fiction genre ever produced in the 1950s. It may be the most paranoid film ever made. There were a number of other similar films being made around the time on alien infiltration and takeover themes – It Came from Outer Space (1953), Invaders from Mars (1953), It Conquered the World (1956), The Brain Eaters (1958) and I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958). There had been a huge boom in alien invader films begun with the success of The War of the Worlds (1953) but this particular body of films took the alien invader genre inward into fascinating psychological places.

In the body snatchers sub-genre of films, alien invaders didn’t arrive in saucers and blow civilisation up so much as they invaded the mind. These alien takeover films were akin to film noir thrillers of the 1940s. Film noir took the standard G-Man and detective films of the 1930s and remade them with a darker spin where the edges of the world the films inhabited was foregrounded to suggest a world of near shadowy darkness, where morals were blurred such that the detective heroes seemed less resolute fighters for law and order than they were the worldweary bastions of hope in a world that was morally decaying. What film noir did in essence was to externalise the moral conflict of the detective story. Around the same time, producer Val Lewton took the monster movie and similarly psychologically externalised it, creating an excellent body of films beginning with Cat People (1942) that inhabit these shadow worlds and hover without resolve between the supernatural and mundane rationalism.

In the same sense, Invasion of the Body Snatchers and the other alien takeover films, as well as works that would follow such as British copies like Quatermass 2/The Enemy from Space (1957) and Village of the Damned (1960) and tv’s The Outer Limits (1963-5) and The Invaders (1967-8), psychologically externalised the central conflict of the alien invader film – they were less films about aliens than they were about alienation. Of these films, Invasion of the Body Snatchers in particular looks back and draws from the physical and photographic style of noir in its creation of shadowy tension and paranoid uncertainty.

The original title for Invasion of the Body Snatchers was Sleep No More, which is telling. For it is really a film about the divide between the fear that nightmares hold and the rationalism that the waking world offers. Invasion of the Body Snatchers seems less about the literal mechanics of alien invasion that it does about a wide-awake nightmare slowly occluding the everyday world and reason itself. Beginning amidst the everyday, the film slowly overturns normalcy in quiet, unexceptional way. Oddities and peculiarities are introduced then dismissed with perfect rationalisations. When the slip into nightmare comes, it is something that has already arrived and overwhelmed with a slick ease, gathering all the details littered throughout about it. Suddenly we are confronted with shock images – a blank unformed body lying on a billiard table or a duplicate of Dana Wynter discovered growing in the cellar.

The film lets all of this to take place in half-shadow at night-time but when it returns to the day it is like a tromp l’oeil optical illusion where everything suddenly reverses itself and what happened is made to appear as though it belongs in the realm of irrational nightmare – the body is gone, there are only shadows in the cellar and the aunt and kid who thought people were different are now acting perfectly normal. The psychiatrist’s explanation the morning after that the pods are part of a mass hallucination becomes so convincing that the film’s entire perspective changes about in a single moment – one believes it because it sounds so rational.

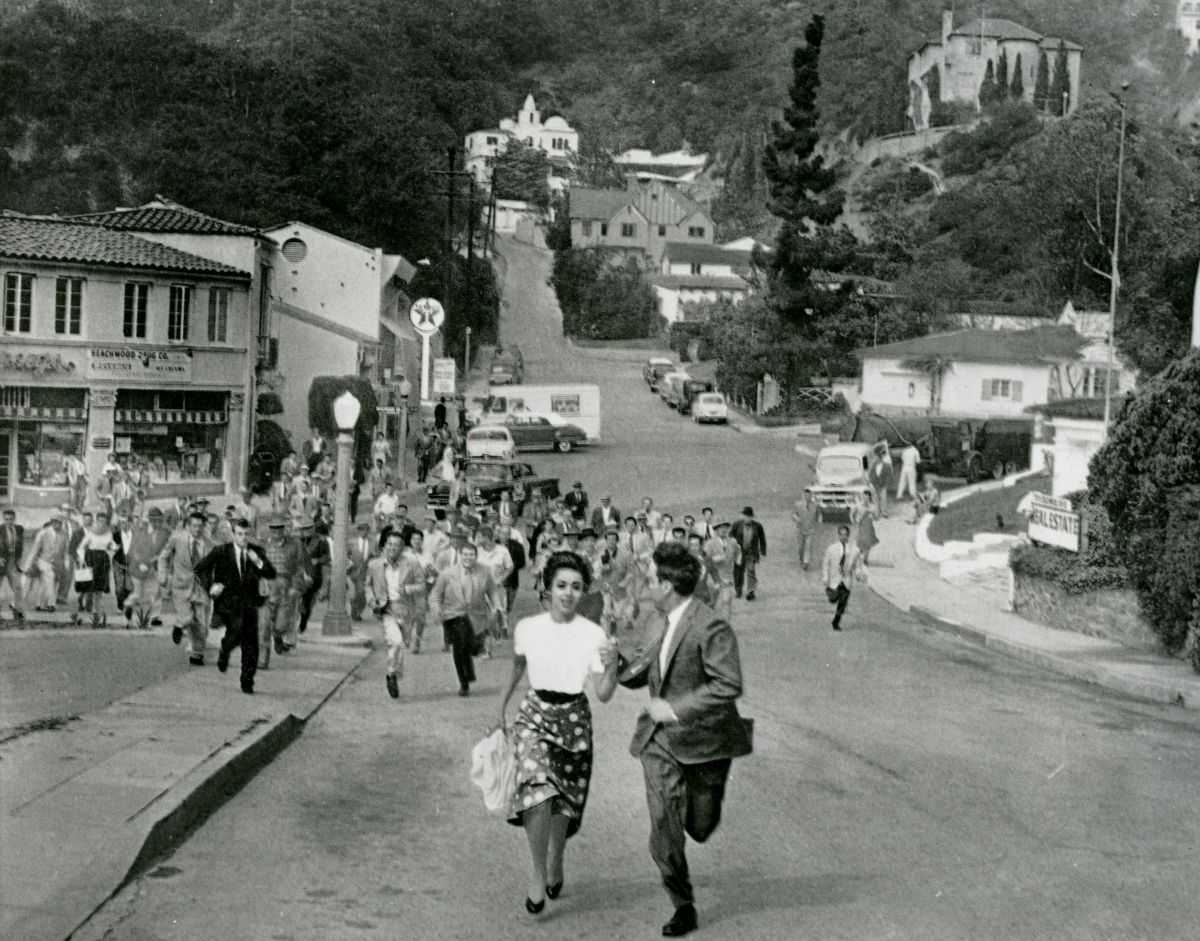

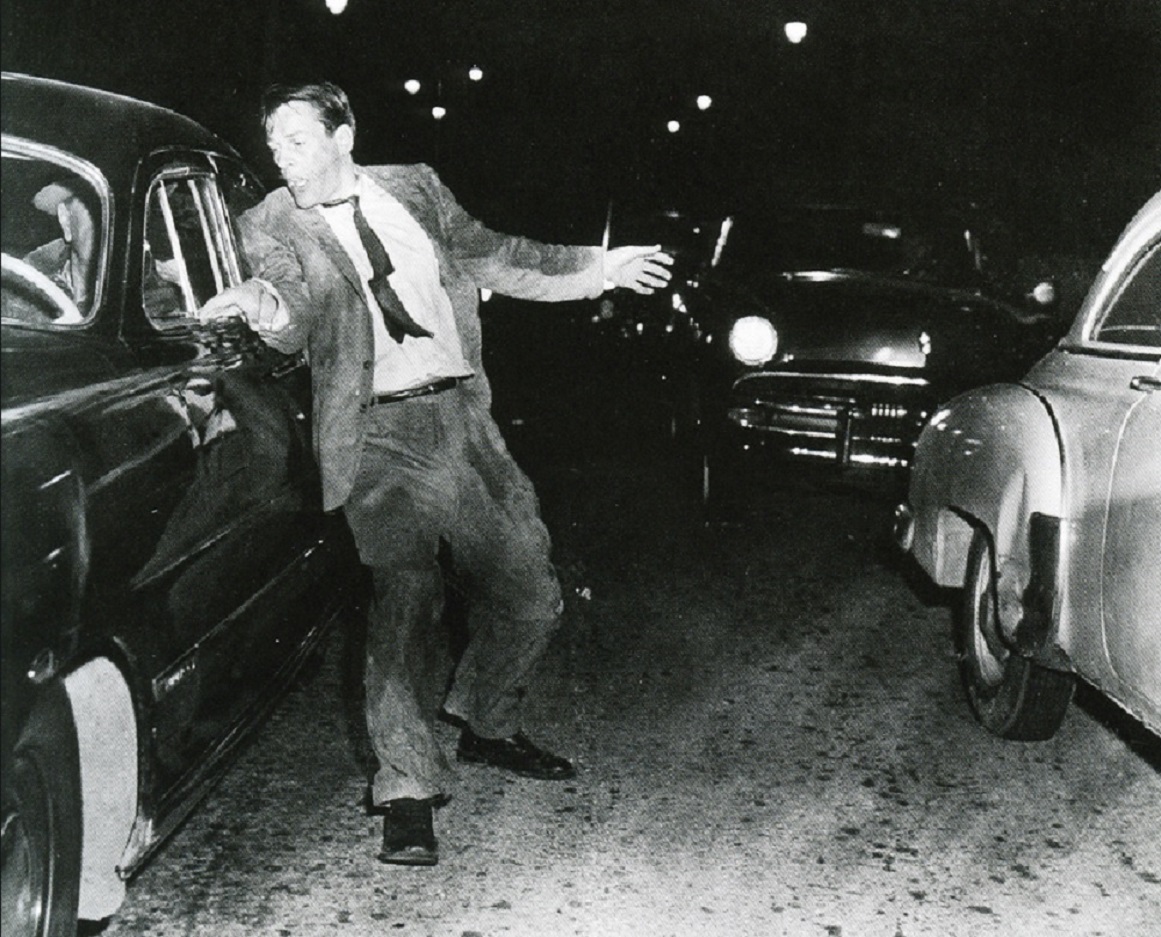

Invasion of the Body Snatchers is a film that uses the fear of night probably more so than any other horror film ever made – night and sleep are the realms of fear, day is the realm of reason. What is interesting is that the film sides with irrationality and night, rather than day and reason. Much of the latter half of the film builds with the relentless sense of things spinning out of control that a nightmare does. The climactic scenes with Kevin McCarthy running on a highway, his cries for help being ignored by the passing cars and his leaping onto the back of a truck only to find it filled with pods makes much more sense in terms of dream logic than rational storytelling.

When the nightmare arrives true and proper, director Donald Siegel dips into his bag of film noir tricks and lets go with everything in its arsenal – shots down tight corridors, silhouettes running against streetlights, tilted angles, closeups on sweaty faces. Some scenes are classic moments of terror – the shots up from under the planks where Kevin McCarthy and Dana Wynter are hiding, with the pod people crossing above calmly assuring them there is nothing to fear; the wide-angled shots out of the office window down onto the public square, which becomes inexplicably frightening the moment all visitors are cleared and the bustle of everyday chaos suddenly turns into something ordered as people start organising the pods to be distributed about the country. There is a wonderfully chill scene eavesdropping on a house where a married couple discuss the baby: “Is the baby asleep yet?” “No, but she will be soon. There’ll be no more tears then.”

The scene in the mine where Dana Wynter draws Kevin McCarthy down into a slow kiss and the camera moves into closeup on her face, showing her black, expressionless wide-open eyes as we joltingly realize she too has been taken over is genuinely scary, a classic moment.

There was a silly framing device tacked on by the studio in which Kevin McCarthy tells his story to a psychiatrist who by the end decides to believe him and immediately goes to call the FBI. One gets the impression that the studio were unable to handle the all-out sense of nightmare that Donald Siegel created and needed to offer audiences the comforting assurance that people would be protected by law and order should such a situation occur. Aside from this, the rest of the film is nightmarishly paranoid – it actually improves over the Jack Finney novel, which had a difficult-to-believe ending where the pods simply give up on humanity and return to space.

The perpetual issue that will forever dog Invasion of the Body Snatchers until probably film becomes obsolete is its being interpreted as an allegory about Communism and the McCarthy witch-hunts of the 1950s. It is questionable if making an anti-Communist allegory was ever Donald Siegel’s intention. To call Invasion of the Body Snatchers a Communist allegory is perhaps to be too literal about it. Rather it seems more the case that it and others in this alien takeover genre tap into an all-pervasive state of mind. Equally as much as a parable about Communism, you could interpret Invasion of the Body Snatchers as a parable against conformity. Donald Siegel after all made that great parable of anti-establishment defiance Dirty Harry (1971).

A strand of thinking runs through 1950s American science-fiction. During this era, America saw itself as a small town. The 1950s was an era of great prosperity but was also an era of great conformity. It was the era of smalltown family values – back in the days when Family Values were universally embraced rather than conservatism’s nostalgic ideals. However, they were values that promulgated an impossible ideal – a middle-class lifestyle of marriage, nuclear family and Good Housekeeping – and refused to accept almost any variation outside of that. Outside of the smalltown state of mind, there was the suspicion that there were forces gathering, things that could rampage across and destroy the smalltown, or more sinisterly that could take over while people weren’t watching and suck out emotions. When Sloan Wilson published The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit (1955) it was a shock wake-up call that people felt dissatisfaction with this Utopian middle-class lifestyle that was being promoted and sold as the post-War ideal.

One can equally see as much any enemy outside, there was the fear in this era that something inside might emerge and peel apart the perfect ideal that this post-War society had created for itself. This was after all the era of HUAC and the McCarthy witch-hunts where you could see not far beneath the idealised storybook image that there was an iron fist determined to enforce that ideal as a norm. It was an era filled with paranoia – wherein people of even suspected Communist leanings were being summarily thrown in jail or blacklisted from the workplace ie. a time when people were encouraged to look at their neighbour and wonder if, while they looked and acted exactly the same, they might not be harbouring anti-American ideals behind the façade. The entertainment industry was one area that was especially targeted in this respect.

Equally, it was an era that also remembered Nazi experiments, the cold chill of a master race eliminating what it is saw as inferior races. America identified itself with warmth, emotion and family values, while correspondingly the nameless threat outside the town was without feeling and had malicious intent toward everything familiar.

The fears that emerge here on film seemed caught between both ends – the fear of something cold and emotionless without and the fear of something that was total anathema to the ideal of Good Housekeeping emerging from beneath the mask of rigidly enforced normalcy. To say that Invasion of the Body Snatchers is an outright allegory about Communism is to be overly literal, rather it seems more like a film about dark opaque things that threaten a placid surface of a mythic ideal of normalcy.

Director Donald Siegel had made a career out of career out of snub-nosed crime thrillers – indeed, he made many of these in the film noir era of the 1940s and 50s. His two other forays into genre territory were the original Dirty Harry (1971), a psycho-thriller that made frequent Siegel collaborator Clint Eastwood’s name, and the lesser-known Eastwood vehicle The Beguiled (1971), a great Southern Gothic melodrama. Siegel also made an appearance as a bartender in Eastwood’s psycho-thriller Play Misty for Me (1971).

There were three remakes:– Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978) and Body Snatchers (1993), which are both excellent films, and the highly disappointing The Invasion (2007). The versatility of the central idea of the Jack Finney story is such that the basic premise can be adapted to the social times that each film was made. Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers could never have been made at a later time, it is too much rooted in the sense of a small cosy American town being alienated. In the 1978 version, Philip Kaufman instead used the pods as a metaphor for urban alienation, while in the 1993 version Abel Ferrara used them to stand in for a shadowy nebulous force that was corrupting society, and the 2007 version made muddled attempts to give it a contemporary spin. Kevin McCarthy also makes a witty cameo, still clutching a pod and in black-and-white, in Joe Dante’s Looney Tunes: Back in Action (2003), as well as the 1978 remake.

Trailer here