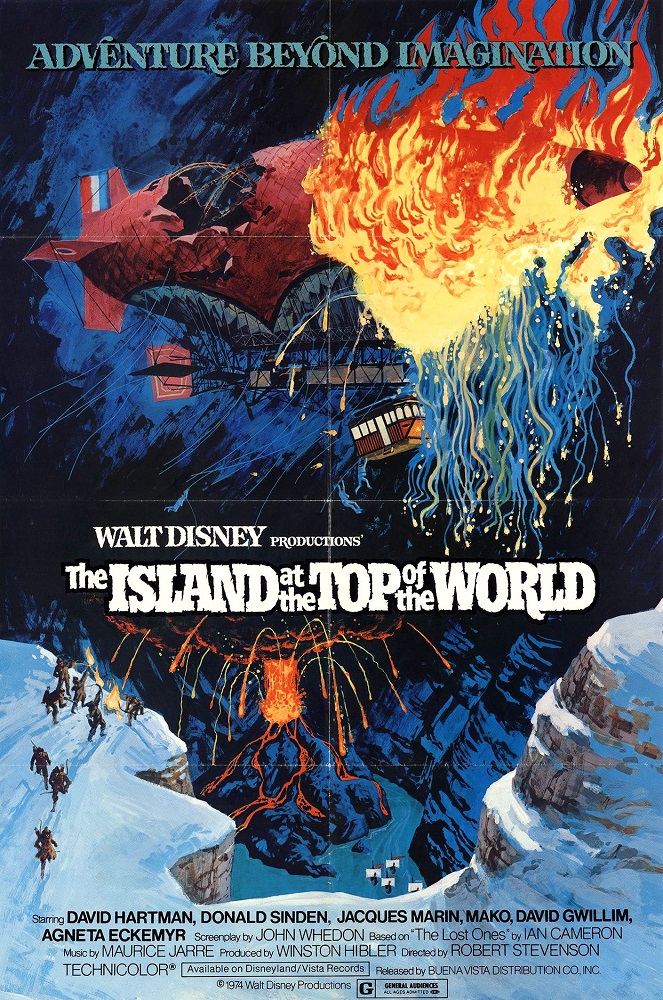

USA. 1974.

Crew

Director – Robert Stevenson, Screenplay – John Whedon, Based on the Novel The Lost Ones by Ian Cameron, Producer – Winston Hibler, Photography – Frank Phillips, Music – Maurice Jarre, Visual Effects – Art Cruickshank & Peter Ellenshaw, Special Effects – Danny Lee, Makeup – Robert J. Schiffer, Production Design – Peter Ellenshaw. Production Company – Disney.

Cast

Donald Sinden (Sir Anthony Ross), David Hartman (Professor John Ivarsson), Jacques Marin (Captain Brieux), David Gwillim (Donald Ross), Agneta Eckemyr (Freyja), Mako (Oomiak), Gunnar Ohlund (Godi)

Plot

1907. Sir Anthony Ross recruits Norse archaeologist John Ivarsson and the French dirigible designer Brieux to go on an expedition to the Arctic in search of Ross’s missing son Donald. The set forth aboard Brieux’s airship The Hyperion. On an island hidden under cloud-cover, they find a race of lost Vikings, living in a green valley kept humid by an active volcano. However, the Vikings believe them to be the invaders that are supposed to spell the end of the world according to the island’s mythology and they are sentenced to death. To escape, they must make their way through the whale’s graveyard just as the volcano starts to erupt.

With this adventure film, Disney sought to regale the heights of their classic 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) and mounted a lavish period lost world adventure. However, The Island at the Top of the World arrived to mixed success. It was greeted with an almost universally mediocre reception, although this author would beg consideration otherwise.

Certainly, the human element is stodgy. The noble explorers it readies are not a very exciting lot, with Jacques Marin’s dimensionless comic Frenchman being a particularly irritable (and racist) caricature. Being a Disney movie, it cannot resist the opportunity to throw in a cute furry animal for the journey – one supposes that there should be some relief to be found in that we are at least spared a cute scene-stealing kid. The Vikings in their fake beards are a boring bunch, a distinct comedown from the optically enlarged lizards and man-eating plants that usually inhabit these lost world fantasies (although it must be said, if nothing else, this is one of the few lost world films that exists within the realms of anthropological plausibility). The most interesting of the characters is that of the Professor, for whom the film seems happy to censure a virtually anything goes Ends Justifies the Means ruthlessness.

Where The Island at the Top of the World achieves particularly well is in the sense of pure spectacle it conjures forth. The special effects are probably the best that the Disney in-house team ever put on screen. The scenes with the model airship crossing the French and Arctic landscapes are flawless textbook examples of travelling matte work. The model airship is astoundingly good – the scene where it is tossed about a mountainside in a storm is absolutely enthralling, and the moment where the balloon rises up free of the gondola, trailing miniature ropes and drifts over the heads of the terrified Vikings is a stunning set-piece.

There are some poor effects in the film, particularly when it comes to some of the back-projection work, most disappointing being the professor’s run against an oncoming lava flow, but these should in no way be counted as marring the flawless work elsewhere. The natural spectacle that the film commands in the name of adventure during the last quarter – chases in the face of lava flows and rivers of water, journeys down into bore holes and caves of ice crystals as they are smashed apart by boulders, the party rowing on ice packs, attacks by killer whales (which are improbably driven away by gunfire) – is magnificent.

Robert Stevenson, who directed much of Disney’s live-action comedy during the previous decade, including the likes of The Absent-Minded Professor (1961), Mary Poppins (1964) and The Love Bug (1969), is a routine director. Indeed, the spectacle here can be attributed more to the sterling work of the effects team – an earlier scene with Jacques Marin attempting to repair a propeller in mid-air is strangely lacking in suspense, while the abrupt changes of scenery early on are dramatically disruptive. Maurice Jarre offers a somewhat literalistic score – the scene where the Eskimos tow the airship down by its ropes for mooring seems to offer an image of bellringers swinging, so Jarre duly offers up cathedral bells on the soundtrack.

British director Robert Stevenson made a number of other films for Disney that include Disney include Darby O’Gill and the Little People (1959), The Absent-Minded Professor (1961), In Search of the Castaways (1962), The Misadventures of Merlin Jones (1963), Son of Flubber (1963), Mary Poppins (1964), The Monkey’s Uncle (1965), The Gnome-Mobile (1967), Blackbeard’s Ghost (1968), The Love Bug (1969), Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971), Herbie Rides Again (1974) and The Shaggy D.A. (1976). Before moving to Hollywood, Stevenson also made the Boris Karloff mad scientist film The Man Who Changed His Mind (1936) and the sf film Non Stop New York (1937).

Trailer here