Crew

Director – Jack Arnold, Screenplay – Harry Essex, Story – Ray Bradbury, Producer – William Alland, Photography (b&w, 3-D) – Clifford Stine, Music – Joseph Gershenson, Makeup – Jack Kevan, Production Design – Bernard Herzbrun & Robert Hoyle. Production Company – Universal.

Cast

Richard Carlson (John Putnam), Barbara Rush (Ellen Fields), Charles Drake (Sheriff Matt Warren), Russell Johnson (George), Joe Sawyer (Frank Daylon)

Plot

Astronomer John Putnam sees a meteor come down in the desert not far from his home. He rushes there, finding a giant geodesic structure and an amoeboid cyclopean creature, just before the creature brings a rockfall down burying the ship. He tries to convince authorities what he saw but nobody believes him. Putnam and then two telephone linemen see the alien flying across the highway. Putnam later comes across the linemen, one cold and emotionless and the other standing by an apparently dead double of himself. He realizes that the aliens have duplicated the linemen, along with others in the town. The aliens kidnap Putnam’s girlfriend, telling him that she will come to no harm if he does not interfere and allow them the 24 hours they need to repair their ship and return home.

It Came from Outer Space is a classic of the 1950s alien invader genre. It came out in the crucial year – 1953 – that unleashed the tide of alien invader films – George Pal’s The War of the Worlds (1953) came out in February of that year, the other alien takeover classic Invaders from Mars (1953) came out in April, less than a month before this. There was also The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), adapted from a Ray Bradbury story, which came out only a couple of weeks after It Came from Outer Space and launched the atomic monster movie genre.

While The War of the Worlds coined the all-out alien invasion, It Came from Outer Space and Invaders from Mars took the theme in more interior psychological directions, crafting eerily paranoid stories. They were less concerned about the world under threat externally than of subversions from within by aliens that steal human bodies and look the same in every way except for emotions. This theme would find grand flowering in later films such as Quatermass 2/The Enemy from Space (1957), The Brain Eaters (1958), I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958), The Day Mars Invaded Earth (1962) and this particular subgenre’s masterpiece Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956).

Of all these body snatchers films, It Came from Outer Space is the only one to feature benevolent aliens or at least ones who only act threatening when they are pushed to it. Indeed, It Came from Outer Space is about the only film other than The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) in the whole of the 1950s not to feature malevolent invading aliens. Like The Day the Earth Stood Still, It Came from Outer Space is critical of humanity’s reaction and shoot-first attitude in the face of the alien – here the aliens only act sinister when redneck attitudes rather than peaceful coexistence comes to the surface.

It Came from Outer Space is a crucial gatefold film in many regards. It was the first screenplay produced by Ray Bradbury – although Bradbury only turned in a treatment and the finished result was rewritten by Harry Essex. (There has been some debate over the years whether the finished result was more due to Harry Essex or Ray Bradbury; certainly, Bradbury was not entirely happy with the results).

It Came from Outer Space also saw the genre debut of director Jack Arnold (1916-1922). Arnold began directing with the tabloid melodrama Girls in the Night (1953) and would go onto make a number of other genre classics including The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), Revenge of the Creature (1955), Tarantula (1955), The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), and the lesser likes of Monster on the Campus (1958), The Space Children (1958), The Mouse That Roared (1959) and Hello Down There (1969), as well as the came up with the story for The Monolith Monsters (1957).

While producer George Pal offered up the most high profile and lavishly budgeted of science-fiction films in the 1950s, Jack Arnold was the genre’s poet. Arnold is always talked about in terms of his ability to craft landscape as metaphor. In films like The Creature from the Black Lagoon and Tarantula, Arnold crafts the desert and rainforest as environments where humanity is seen as almost an alien intruder against the immensity of the geological age. In It Came from Outer Space, Jack Arnold makes the desert into a desolate, alien world. The film hovers on a shadowy twilight edge where things are never what they seem. Gnarled trees appear to be ghosts and there is one eerie scene where an alien tracks silently across the desert scaring little animals in its path.

There is some remarkably haunting and evocative dialogue:– “You can see lakes and rivers that aren’t there and sometimes you think the wind gets into the wires and sings to itself,” says one of the linesmen describing the desert. (With lingeringly beautiful dialogue like this, it is hard to see why Ray Bradbury was unhappy with the finished screen product).

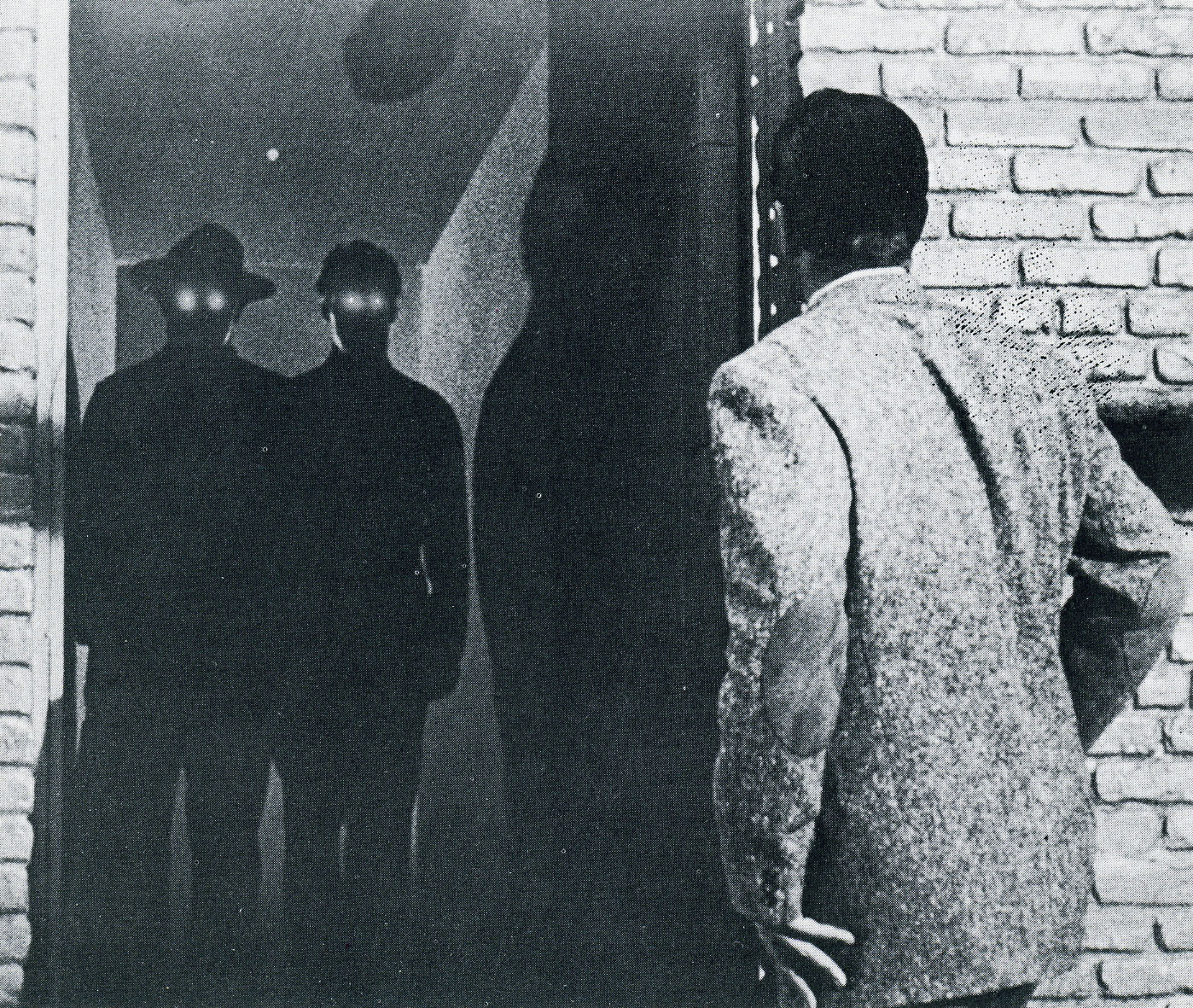

There are some beautiful moments to the film – Richard Carlson’s original discovery of the alien ship, and some eerily off-centre scenes with the duplicated linesmen emerging from behind a rock holding hands and looking at the sun without blinking, or standing silhouetted in a darkened doorway with glowing eyes.

It Came from Outer Space was made in 3-D and is sometimes revived in that format today. There are a few gimmicky into-the-lap effects of falling rocks and the meteor appearing out of the screen but mostly Jack Arnold uses the 3-D towards the less common effect of perspective depth, trailing telephone wires off into the distance, shooting up into linesmen’s ladders and the like. The 3-D gives a more visual edge to some scenes – the descent into the crater, the gauzy shots from the alien’s point-of-view.

Mostly, what carries It Came from Outer Space is its literate script and Jack Arnold’s atmosphere. The only quibbles one has is the conception of the alien, which is surely far too ungainly to be able to fly. The heavenly choruses that accompany its flight also seem to be overdoing it slightly. Otherwise, It Came from Outer Space is a genuine classic of the era.

It Came from Outer Space was later poorly remade as the cable movie It Came from Outer Space II (1995). Alien Trespass (2009) was an affectionate homage.

Other genre films from Ray Bradbury’s genre works are:– the aforementioned The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms from his short story The Foghorn; Francois Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 415 (1966) from his dystopian novel; The Illustrated Man (1969) from his short story collection; the tv movie The Screaming Woman (1972) adapted from his story about a woman buried alive; the dreary tv mini-series The Martian Chronicles (1980) from his classic book; the tv movie The Electric Grandmother (1980); the screenplay for the fine Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983) from his own novel; the tv anthology series The Ray Bradbury Theater (1986-92) where he adapted his own stories and hosted the series; his screenplay for the animated adaptation of the classic comic-strip Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland (1989); the screenplay for the animated children’s film The Halloween Tree (1993); Stuart Gordon’s adaptation of The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit (1998) about a seemingly magical suit; A Sound of Thunder (2005) based on Bradbury’s classic time travel story; Chrysalis (2008) where a man mutates into another lifeform; and the tv movie remake of Fahrenheit 451 (2018).

Producer William Alland made a number of other science-fiction films during the 1950s. He produced most of Jack Arnold’s other films, along with the likes of This Island Earth (1955), The Mole People (1956), The Deadly Mantis (1957), The Land Unknown (1957), The Colossus of New York (1958) and the tv series World of Giants (1959). Harry Essex was a regular screenwriter of the era and, along with numerous crime thrillers, wrote the genre likes of Man Made Monster (1941) and The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), before going onto direct two extremely cheap monsters movies – Octaman (1971) and The Cremators (1972). Richard Carlson also became a leading man in science-fiction films of the era, including the likes of The Magnetic Monster (1953), Jack Arnold’s The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), The Maze (1953), The Power (1968) and The Valley of Gwangi (1969), while he both starred in and directed the interesting science-fiction film Riders to the Stars (1954).

Trailer here