USA. 1993.

Crew

Director – Steven Spielberg, Screenplay – Michael Crichton & David Koepp, Based on the Novel Jurassic Park (1990) by Michael Crichton, Producers – Kathleen Kennedy & Gerald R. Molen, Photography – Dean Cundey, Music – John Williams, Full Motion Dinosaur Supervisor – Dennis Muren, Special Dinosaur Effects Supervisor – Michael Lantieri, Dinosaur Supervisor – Phil Tippett, Live Dinosaur Supervisor – Stan Winston, Production Design – Rick Carter. Production Company – Amblin/Universal.

Cast

Sam Neill (Dr Alan Grant), Laura Dern (Dr Ellie Sattler), Richard Attenborough (John Hammond), Jeff Goldblum (Ian Malcolm), Ariana Richards (Alexis Murphy), Joseph Mazzello (Tim Murphy), Bob Peck (Robert Muldoon), Martin Ferrero (Donald Gennaro), Wayne Knight (Dennis Nedry), Samuel L. Jackson (John Arnold)

Plot

Palaentologists Alan Grant and Ellie Sattler and mathematician Ian Malcolm are brought to a remote island off the coast of Costa Rica by billionaire John Hammond to give their opinion on Hammond’s latest project – Jurassic Park. They are astounded to discover that Hammond’s scientists have recreated living dinosaurs using DNA extracted from the stomachs of prehistoric blood-sucking insects that have been preserved in amber. Malcolm, a chaos mathematician, denounces Hammond’s work as dangerous on the grounds that Hammond is not able to predict the enormity of what he has done. Malcolm is proven right shortly after as one of Hammond’s employees, attempting to steal dinosaur embryos for a rival corporation, shuts down the security grid in order to make his escape. With the security grid down, the electric fences that keep the dinosaurs penned are turned off and the humans find themselves hunted by ferocious creatures.

Jurassic Park came with perhaps the most intensive and culturally saturated commercial tie-in campaign ever conducted for a film up to that point. Everything from blow-up and toy dinosaurs, to the standard calendars, Making of books and action figures, to Jurassic Park bread, yoghurt and fast food. There did seem something faintly amusing about the manufacturedness of the marketing campaign – dinosaur toys, books and posters are not exactly new and it was not as though Jurassic Park had the sole copyright on dinosaurs – which placed it in the odd position of trying to convince its public that its dinosaur tie-ins were more legitimate than all the other dinosaur toys out there for the simple reason that these ones had the film’s name and copyright on them. In New Zealand (at least during the 1980s/90s), such saturation marketing tended to have a rebound effect, with people becoming so reminded that the film must be of such significant importance that they will want to buy all these keepsake mementos that when the film did eventually open, usually some six months after its Stateside premiere, the reaction had gone from anticipation to blase. It happened with Batman (1989) and it happened here again – by the time Jurassic Park eventually did appear, it was greeted with a resounding “neat dinosaurs, shame about the plot” reaction. Whatever the case, the marketing at least worked, with Jurassic Park rocketing to the top of the All-Time Highest Grossing box office films list and being one of the few films in the 1990s to give director Steven Spielberg’s own E.T – The Extra-Terrestrial (1982) a good challenge for the No.1 spot.

The upshot of the marketing campaign (and the carefully calculated trailers that only released brief glimpses of the dinosaurs) was that it manufactured a want. It begat a single anticipation of its audience – the expectation that the film would produce dinosaurs. One can see it in the way the audience greeted the film – they fidgeted through the first fifteen minutes and the lectures – amiably disguised, nevertheless still lectures – on the viciousness of velociraptors, whether dinosaurs were birds, chaos theory and dinosaur DNA in wait. This was clearly an audience that wanted to see dinosaurs.

The entire success of Jurassic Park centred around whether or not Steven Spielberg could provide dinosaurs. The moment the first brontosaurus appeared on screen, lazily nibbling at the tops of trees, there with a stunning fullness of realisation that up to that point had been unseen on the screen – it produced a collective sigh of awe. The answer, of course, was a resounding yes – Steven Spielberg had taken the audience’s want and produced a banquet. With the first sight of the brontosaurus, it is a moment one realises that Spielberg and the entire thrust of the film and marketing campaign has deliberately led one up to. It is a magician’s trick – making an audience want to see magic before it is provided, something that is even evident on screen in the way that Spielberg studiedly shows us the characters astounded reactions to the dinosaur before he allows us, the audience, to see them.

Jurassic Park marked a return to the type of filmmaking that Steven Spielberg made his name with at the start of his career – the lean, economically stripped-back, seat-edge rollercoaster rides of Duel (1971) and Jaws (1975). It seems a conscious attempt to turn back away from the big budget-itis and increasingly woolly soft-headedness that has marked all of his films of the last decade – about everything he has directed from E.T. onwards. More importantly for Spielberg, it was a decade that was marked by a string of either critical – the Indiana Jones sequels, Hook (1991) – or public failures – Empire of the Sun (1987) – often both – Twilight Zone – The Movie (1983) and Always (1989).

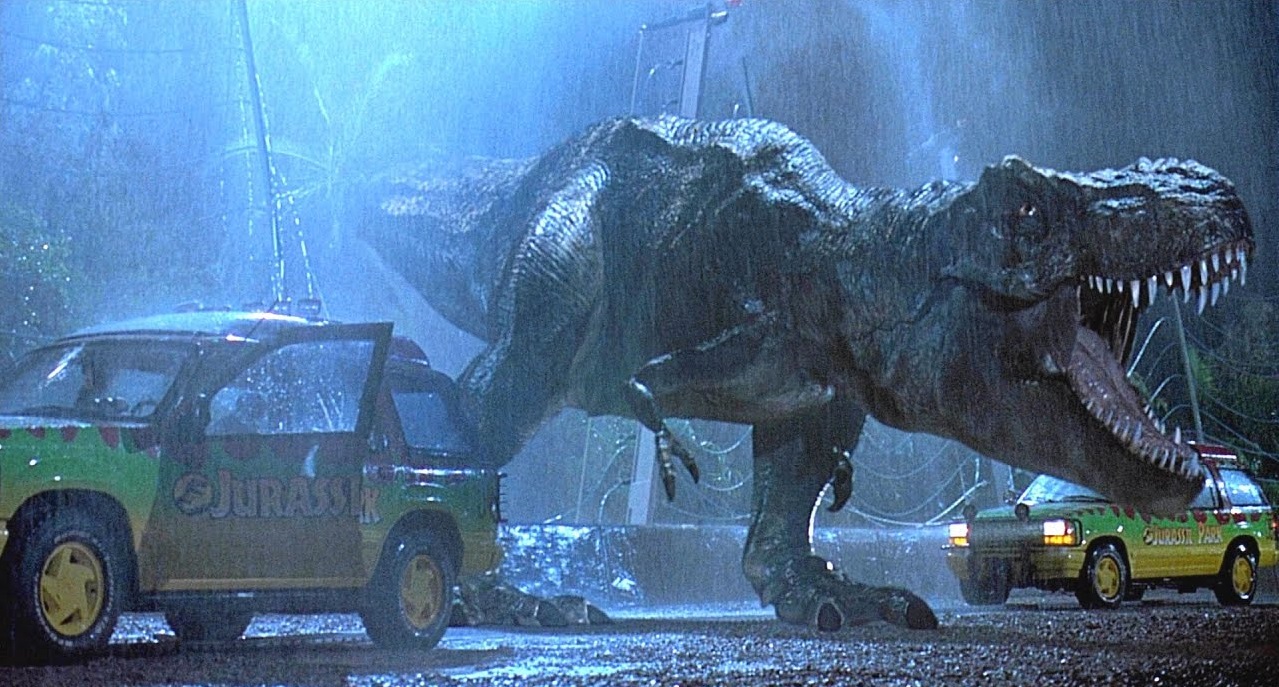

Jurassic Park is not free of budget-itis – indeed, it was Steven Spielberg’s most expensive film up to that point. However, Spielberg has set out to be scary and the film contains some of the best seatrest-gouging moments one has seen on screen in some time – particularly the scenes with the velocraptors chasing the children through the kitchens. The most seat-edge set-piece in the film is undoubtedly the attack of the T-Rex on the stalled Jeeps, with it spinning the Jeep around with its snout and smashing through the windows to get at the terrifyingly vulnerable children inside, charging after a defenceless Jeff Goldblum as he stands in the open waving a flare to attract its attention, and crashing into a toilet and almost casually snapping up the cowering Martin Ferrero in its mouth. It is a sequence that is made all the more terrifying for Spielberg’s willingness to break one of Hollywood’s cardinal unwritten rules – about not endangering the lives of children – at any moment, one fully believes their lives are in danger.

The full-blooded appearance of the T-Rex bursting through the electric fence in the rain, accompanied by a wonderfully thrilling digitally mastered roar, is also a stunning moment, one that explodes with all primal ferocity that the first appearances of say The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) and Godzilla (1954) did in the early 1950s. It is truly like such creatures have been taken right out of the Cretaceous and let loose.

For all that, Jurassic Park‘s greatest fault is that it is a good film, but one is left feeling that it should have been more. Steven Spielberg, particularly in the Indiana Jones sequels and Hook, has a tendency to sketch his films in tones so broad that they verge on caricature. That is something that faults Jurassic Park too. It has a good cast, most of whom perform efficiently.

Many of the supporting characters seem too broad as characters to ever be believable – Martin Ferrero’s cowardly lawyer seems too nervous to ever emerge as someone capable of managing the finance for a multi-billion dollar amusement park; Jeff Goldblum’s playing of the chaotician is suitably flaky and intense and given to wry throwaway lines but the character never manages to impress us that he is a mathematical genius; similarly Richard Attenborough’s Walt Disney-inspired John Hammond seems too grandfatherly, too soft-headed, too naive and incapable of threat to convince us he is an astute billionaire businessman. Although, in the bad acting stakes, the worst offender period is Wayne Knight’s giggly irritable computer buff, an inane performance that more properly belongs as a villain in a children’s film. The kids’ scenes come with a surprising and tolerably small degree of sentiment. Indeed, the best performance in the film comes from this quarter – Joseph Mazzello is anonymous, but Ariana Richards’ playing of the 12 year-old is welcomely tough and resourceful.

The film conducts a fair adaptation of Michael Crichton’s 1990 novel. The book has been efficiently trimmed for the screen without losing any of the major aspects. It does gain, not too surprisingly being a Steven Spielberg film, a subplot about how the paedophobic Sam Neill character comes to like children. That said, the result does not always work on screen – the ideas behind dinosaur-cloning and chaos theory require difficult concepts at the best of times and in trying to encapsulate these for its audience in only a couple of minutes, the film leaves behind almost all of those who do not have a working knowledge of either subject. (The great irony of the film is that its success and creation of the dinosaurs is dependant on a technology – CGI animation – that Michael Crichton predicted in his science-fiction film Looker (1981), but saw there as something sinister).

A more subtle difference that permeates the film is its moral message. In the book, Michael Crichton, the perpetual sceptic of the benefits of technology, made some characteristically potent points about the responsibility of science and latched onto chaos theory with an almost religious fervour to authenticate these. Chaos theory is a mathematical concept about the inherent unpredictability of complex systems but in Michael Crichton’s eyes it becomes more of a justification for an inherent belief in Murphy’s Law. In the film, the finer points of explanation and much of the subtlety of Michael Crichton’s argument have been pared away to an absolute minimum, meaning that all the chaos theory seems to be there to do is work up an old “There are some things humankind was not meant to interfere with,” presented with unsubtly bombastic regard. The fact that this is closely tied to several ponderous comments about over-reliance on computer systems leaves the film beating its Crichton-esque anti-technological tub with an unduly heavy hand.

Steven Spielberg followed this with the immensely disappointing sequel The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997). This was followed by the slightly better Jurassic Park III (2001) where Joe Johnston inherited the directorial reins. A Jurassic Park IV was announced off and on ever since 2001 and finally emerged as Jurassic World (2015), followed by Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom (2018), Jurassic World: Dominion (2022) and Jurassic World: Rebirth (2025), as well as the animated tv series spinoff Jurassic World: Camp Cretaceous (2020-2). Jurassic Park was re-released in 3D in 2013, the 20th anniversary of its release.

Jurassic Park gave a sudden boost to the career of the then declining career of Michael Crichton and in the next few years Crichton became one of the hottest film-adapted authors in Hollywood with the likes of Rising Sun (1993), a superior adaptation of Crichton’s blatantly racist book about Japanese business practice; Barry Levinson’s adaptation of Disclosure (1994), Crichton’s novel about sexual harassment, which contains some science-fiction elements; the lost world film Congo (1995); Crichton’s original screenplay Twister (1996) about tornado chasers; Levinson’s underrated Sphere (1998) about the investigation of a crashed UFO; John McTiernan’s The 13th Warrior (1999), an historical epic about the meeting between Vikings and Neanderthals; Richard Donner’s dull adaptation of Crichton’s Timeline (2003) about time travel to Mediaeval France; the tv mini-series remake of The Andromeda Strain (2008); and the tv series remake of Westworld (2016-22). Earlier films adapted from Crichton’s books are the extra-terrestrial virus film The Andromeda Strain (1971) and the neurosurgical Frankenstein film The Terminal Man (1974). Crichton also created the hit hospital drama ER (1994-2009). Michael Crichton’s films as director were Westworld (1973) about an android amusement park that goes amok; the medical conspiracy thriller Coma (1978); The Great Train Robbery (1979) about a Victorian train heist; Looker (1981) about virtual models; Runaway (1984) about a police force to stop amok robots; and the courtroom thriller Physical Evidence (1989).

Steven Spielberg’s other genre films as director are:– Duel (1971), LA 2017 (1971), Something Evil (tv movie, 1972), Jaws (1975), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), E.T. – The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Twilight Zone – The Movie (1983), Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), Always (1989), Hook (1991), A.I. (Artificial Intelligence) (2001), Minority Report (2002), War of the Worlds (2005), Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), The Adventures of Tintin (2011), The BFG (2016) and Ready Player One (2018). Spielberg has also acted as executive producer on numerous films – too many to list here. Spielberg (2017) is a documentary about Spielberg,

Trailer here (3D Re-release Trailer)