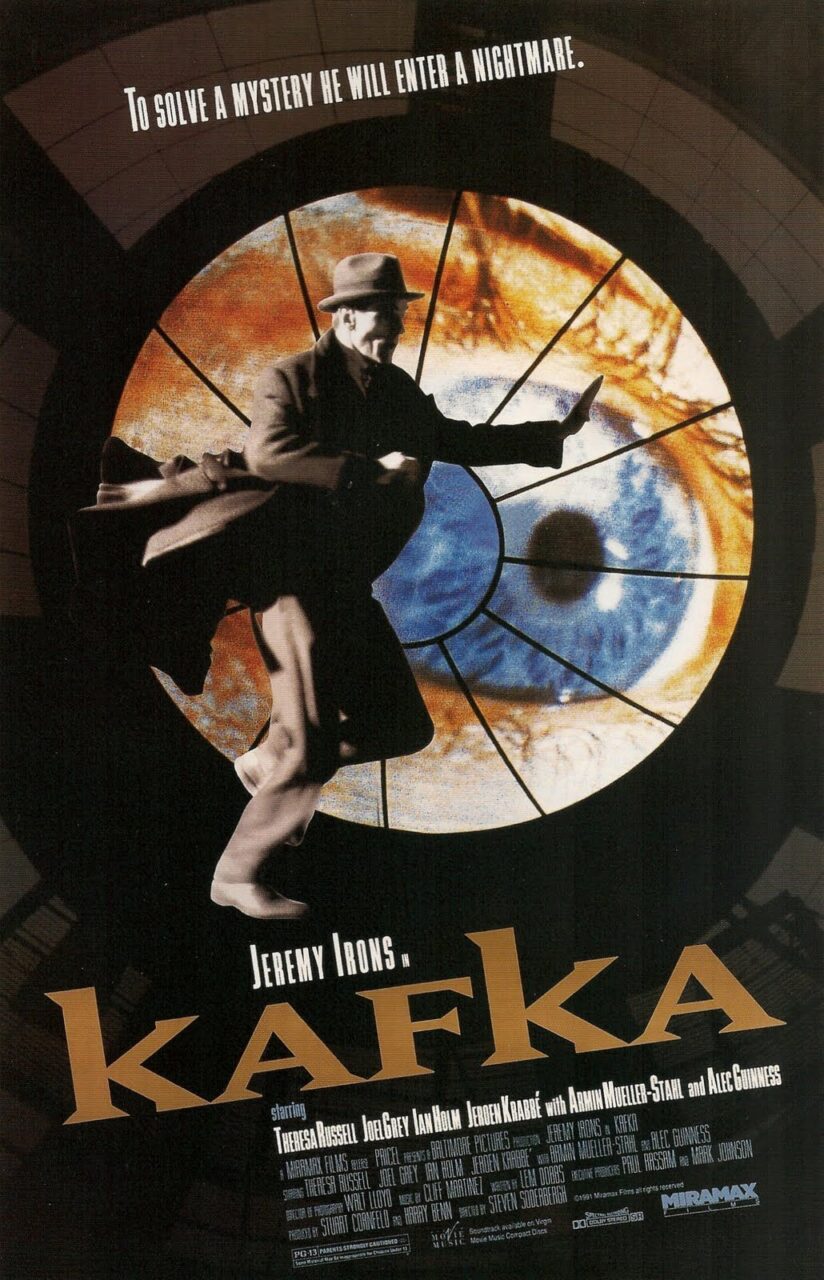

USA. 1991.

Crew

Director – Steven Soderbergh, Screenplay – Lem Dobbs, Producers – Harry Benn & Stuart Cornfeld, Photography (b&w + some scenes colour) – Walt Lloyd, Music – Cliff Martinez, Special Effects Supervisor – Ian Wingrove, Production Design – Gavin Bocquet. Production Company – Baltimore Pictures.

Cast

Jeremy Irons (Franz Kafka), Ian Holm (Dr Murnau), Theresa Russell (Gabriela Rossan), Alec Guinness (The Chief Clerk), Joel Grey (Burgel), Armin Mueller-Stahl (Inspector Grubach), Jeroen Krabbe (Bizzlebeck), Keith Allen (Ludwig), Simon McBurney (Oscar)

Plot

Franz Kafka is a clerk in the labyrinthine bureaucracy of the Workers and Accident Association insurance company in Prague. He spends his spare time writing stories. Kafka becomes concerned when co-worker Eduard Raban goes missing and later turns up murdered. His attempts to learn what happened lead him to a co-worker Gabriela Rossan who was having an affair with Eduard. Gabriela draws Kafka into the company of a group of revolutionaries but then she too goes missing. After being attacked by an insane disfigured killer, Kafka decides he must illicitly enter the all-powerful castle that overlooks the town and seek the truth amid the sinister experiments being conducted there.

Franz Kafka is perhaps one of the key writers of the 20th Century. Indeed there are few others writers who seem to so essentially embody the great 20th Century existential crisis. Kafka was born in Prague in 1883. He received a law degree and then became a clerk in the Worker’s Accident Insurance Association but was forced to retire due to severe tuberculosis, dying only at the age of 41 in 1924. Kafka’s life seems one as anonymous and powerless as any of the characters in his novels – he was small of build; felt dominated his entire life by a disapproving father; spent many years as a low-level bureaucrat; never married; and most importantly and, surprisingly considering the stature his work has, never published any of his works during his lifetime. Indeed, Kafka’s anonymity was such that he left instructions with his friend Max Brod that his works be destroyed after his death and it was only through Brod’s efforts that Kafka’s novels ended up being published, even though none were ever completed. The crucial works that survive are the novella The Metamorphosis (1915) about a man who inexplicably transforms into an insect; Kafka’s most famous work, The Trial (1925) about a man who is placed on trial for reasons that are utterly unfathomable; The Castle (1926) about the frustrated attempts of a man to gain access to the authorities inside a vast castle; and Amerika (1927) about an immigrant trying to understand a surreal, entirely alien country.

Kafka was made as part of a spate of Kafka adaptations/homages that came out all in the space of around two years in the mid-1990s. These also included a new version of The Trial (1993), the 1993 restoration and re-release of the Orson Welles’s The Trial (1962), a Czech adaptation of Amerika (1994), two versions of The Castle (1994 and 1997) and Woody Allen’s comedic homage Shadows and Fog (1991). Kafka is not so much a Franz Kafka biopic as it is akin to Wim Wenders’ Hammett (1983) or maybe Time After Time (1979), which had H.G. Wells building his own time machine and hunting Jack the Ripper, wherein the author’s biography and fiction are blurred together.

Kafka vaguely touches point with some images of Kafka’s stories – a castle over the town, sinister police interrogations. Equally though, Kafka is not very conversant with Franz Kafka’s biographical details – one of the most pertinent facts about Kafka’s life was that all his works were published posthumously and he regarded them as worthless, while the film has them published and people commenting on them.

Kafka was the second film from Steven Soderbergh. Soderbergh then only had the international arthouse hit of Sex, Lies and Videotape (1989) to his name. Someone – in fact Barry Levinson’s Baltimore Pictures – had clearly thrown a good deal of money at Soderbergh, as evidenced by the distinguished name cast he manages to array.

Alas, the idea went astray and Kafka was a big flop and received almost universally mediocre reviews. None of Steven Soderbergh’s subsequent films – The Underneath (1995), Gray’s Anatomy (1996) and Schizopolis (1996) – raised much enthusiasm from audiences either and for a time Soderbergh seemed to only be a one-hit wonder. However, in the late 1990s, Soderbergh found his second wind and bounced back to considerable form and critical acclaim with the impressive, coolly intellectualised likes of Out of Sight (1998), The Limey (1999), Erin Brockovich (2000), Traffic (2000), Ocean’s Eleven (2001) and Solaris (2002).

In Kafka, Steven Soderbergh occasionally hits upon a Kafka-esque atmosphere of paranoid uncertainty, of protagonists being trapped in a world that operates on rules beyond their understanding. However, the addition of two annoyingly buffoonish assistant clerks played by Keith Allen and Simon McBurney tends to topple the Kafka-esque mood over into something more resembling Pinter-esque Theatre of the Absurd. Soderbergh generates some decent intensity in the scenes where a madman bursts in through a bathroom and chases Jeremy Irons down through the elevator but there is never a sense of what people call “the Kafka-esque nightmare,” of a protagonist being trapped in a world that operates on rules they are not privy to.

The film bursts into colour for the climactic venture into the castle. Here Soderbergh peculiarly turns Kafka into a mad scientist film of sorts, although what Ian Holm’s scientist is actually trying to achieve is never made clear. Soderbergh and scriptwriter Lem Dobbs (who also wrote Dark City (1998) and Soderbergh’s The Limey) also cannot quite resist the modern temptation to place Kafka alongside German Expressionist cinema, thus we get references to the “Orlac claim” (after The Hands of Orlac (1924) about a pianist who found he was being possessed after receiving the transplant of a murderer’s hands) and a Dr Murnau (after F.W. Murnau the director of Nosferatu [1922] who was immortalised in Shadow of the Vampire [2000]).

Jeremy Irons, excellent actor that he is, is miscast playing Kafka. Jeremy Irons is far too handsomely intense – the sense of the person you get reading Kafka’s work and biographical portraits is of someone mousy and anonymous. What one imagines the role of Kafka to be like would be something more akin to John Hurt’s portrayal of Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984).

The production has certainly been beautifully mounted. There is an excellent music score. The film was shot on location in Kafka’s home turf, Prague, which has been exquisitely photographed in black-and-white and lends a wonderfully shadowy sinisterness. Ultimately though, Kafka amounts to surprisingly little. You are never sure what the mad scientist elements and the German Expressionist homages are meant to mean. While Steven Soderbergh achieves a dour, occasionally paranoiac mood, Kafka is a film that feels like it has been elaborately contrived without any real point.

Steven Soderbergh’s other film of genre interest as director are the surreal Schizopolis (1996), the remake of Solaris (2002), the viral outbreak film Contagion (2011), the asylum horror film Unsane (2018) and the ghost story Presence (2024). Soderbergh also wrote and produced the English language remake of Nightwatch (1998). Soderbergh has also produced a number of films, including the genre likes of Pleasantville (1998), Christopher Nolan’s remake of Insomnia (2002), the time travel film The Jacket (2005), Richard Linklater’s Philip K. Dick adaptation A Scanner Darkly (2006), the ghost story Wind Chill (2007), the evil child film We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011) and Bill & Ted Face the Music (2020).

Trailer here