USA. 1976.

Crew

Director – Michael Anderson, Screenplay – David Zelag Goodman, Based on the Novel by George Clayton Johnson & William F. Nolan, Producer – Saul David, Photography – Ernest Laszlo, Music – Jerry Goldsmith, Visual Effects – L.B. Abbott, Additional Visual Effects – Frank Van Der Veer, Mattes – Matthew Yuricich, Special Effects – Glen Robinson, Makeup – Terry Smith & Harry Thomas, Art Direction – Dale Henessey. Production Company – MGM.

Cast

Michael York (Logan), Jenny Agutter (Jessica), Richard Johnson (Francis), Peter Ustinov (Old Man), Farrah Fawcett-Majors (Holly), Roscoe Lee Brown (Box)

Plot

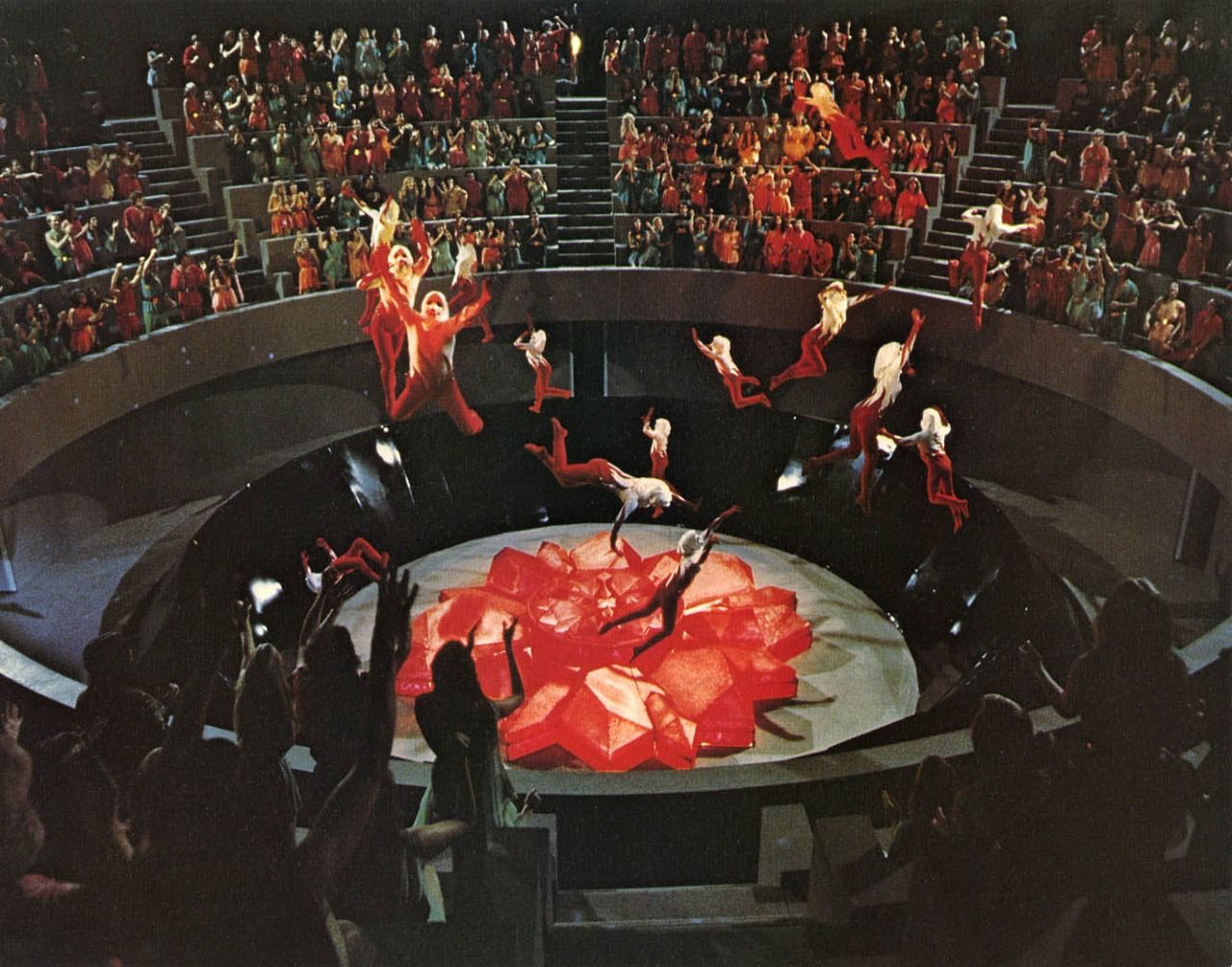

It is the 23rd Century. The populace of the future live lives of languid pleasure in vast domed cities – the only catch being that they are not allowed to live beyond the age of thirty. When they turn thirty, they must go to their deaths in the ceremony of Carousel where they are blown apart in a mid-air anti-gravity field with the promise of being reborn. However, there are those who refuse to accept death and become Runners, seeking the mythical place of asylum known as Sanctuary. An elite police force, known as Sandmen, has been created to hunt the Runners. The city’s controlling computer accelerates the lifeclock of the Sandman Logan and sends him to infiltrate the Sanctuary line. Falling in with another Runner Jessica, Logan travels through the Sanctuary underground, all the while pursued by his best friend and comrade Francis. In venturing outside the domed city, Logan and Jessica instead come to realise the true nature of their world.

Logan’s Run was an A-budget science-fiction production made at a time just before science-fiction was the blockbuster genre it is today. The film was a considerable success, even though it received an almost universal panning from mainstream critics and genre fans alike.

Logan’s Run is a film that straddles two eras. It has clearly been given birth to from the Dystopias of the late 1960s/early 1970s like 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), THX 1138 (1971), Z.P.G. (Zero Population Growth) (1971), Zardoz (1974) and Rollerball (1975), as well as the satiric youth revolution films of the era such as Wild in the Streets (1968) and Gas, or It Became Necessary to Destroy the World in Order to Save It (1970). It features the same cleanly polished antiseptic future, the same anti-technological fears of controlling super-computers and the same visions of hedonistic populaces living in narcotised bliss that run through these films.

At the same time, Logan’s Run is also a film of the new science fiction boom that arrived the following year with Star Wars (1977). Unlike the Dystopian films of the 1970s, it is less concerned with the struggle for individuality than in being an adventure film and a special effects spectacle. As opposed to the post-2001 films, the background of the future is wielded not in terms of oppressively downbeat antisepticism but in terms of providing epiphanies of wonder.

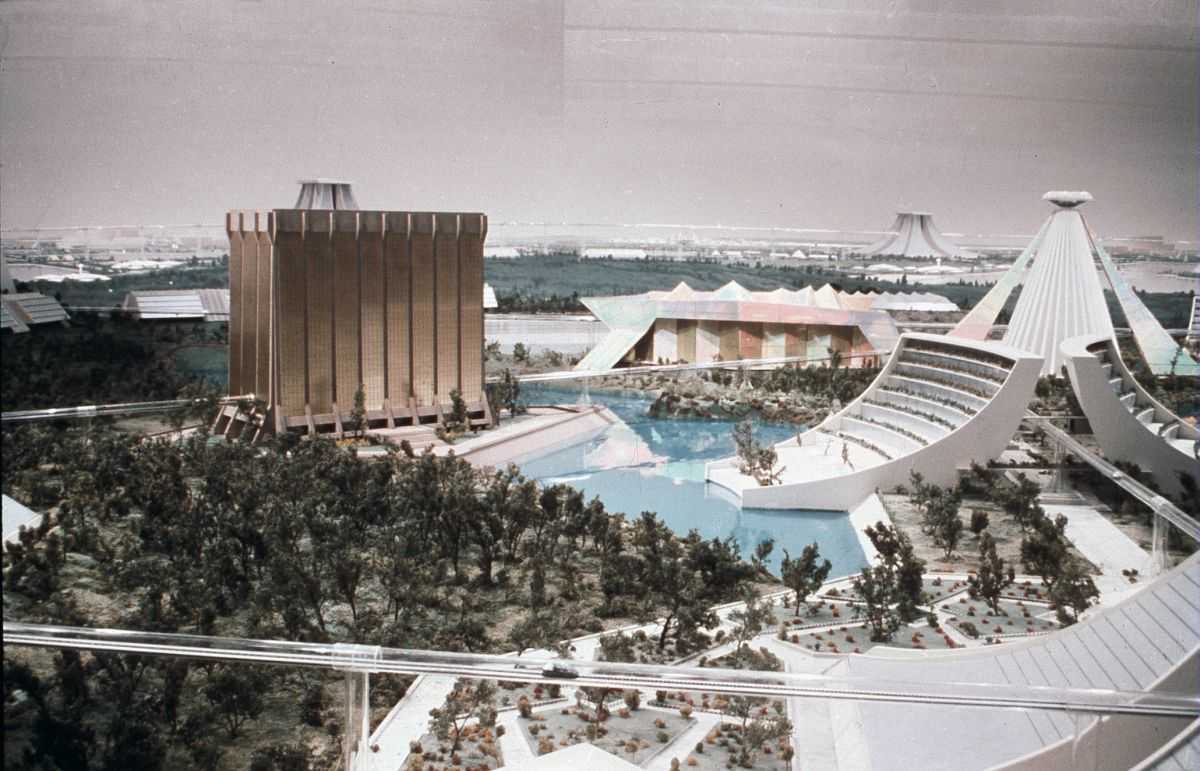

The amount of production value lavished on Logan’s Run is amazing. The sets are stunning – Carousel, the tiered arena all in grey with glow-in-the-dark figures twirling in mid-air and a giant stylised representation of a lifeclock in pink in the centre; the city interior like an ultra-modern shopping mall, all escalators, gleaming chromium and glass; the New You with its glittering spider-like robotic diagnostic bed; and the amazing model cityscapes with the tiny mazecars buzzing through tubes and between buildings and beautifully sculpted model gardens and lakes.

Of all the pastel-kaftaned and plastic vacuform futures science-fiction has conceived for itself from Frank R. Paul to Things to Come (1936), Logan’s Run is both one of the prettiest and one of the emptiest. William F. Nolan and George Clayton Johnson’s original 1967 novel is a lively, highly readable work of science-fiction; the film eviscerates it to little purpose. There are some pluses with the adaptation – Francis is made a stronger protagonist and the double identity of Ballard eliminated, which was never a convincing aspect of the book. The death age is upped from twenty-one to thirty, which certainly makes sense from a casting point-of-view (even though of the actors cast Michael York was 34 at the time and Jenny Agutter 24).

Elsewhere though, the film is gutted of any socio-political milieu. Carousel and the death age are just facets of a society that swim in a void free of any significance – the book was a satiric escalation of the youth revolution of the 1960s where it was postulated that youth had come to dominate the whole world and people over the age of twenty-one were euthenised to keep population numbers down.

In the film, the whole world seems to have been concentrated in a single domed city while the outside is abundant and new again, yet empty of people. There is no mention of overpopulation, yet we are given no idea why this society kills its youth, how or why the Sandmen were set up, or why the society maintains the pretence of Carousel. Even sillier, the film eliminates the existence of Sanctuary – there is a Runner underground helping people, but then the film bizarrely reveals that Sanctuary doesn’t exist, which beggars the obvious question – where is the underground sending all the Runners it aids to?

Similarly, the film throws in a jumble of science-fiction tropes – teleportation systems, test-tube populations, mad robots harvesting plankton and preserving humans for never-specified reasons, computers that mindlessly blow up when faced with imponderables – that seem arbitrarily pasted in. The city ranges from the ocean depths to the Arctic – typical of the film’s nonsensical conceptual patchwork is where Logan and Jessica burst through the walls of Box’s Arctic ice caverns to find a desert landscape on the other side.

If the book was a response to the youth revolution of the 1960s, then the film is a conservative rejoinder to it. Logan’s Run is not too dissimilar to George Lucas’s THX 1138 in its theme of two lovers fleeing a hedonistic, hermetically-sealed society. However, where Lucas ended with Robert Duvall’s THX emerging out of the city into the sunlight of the real world, Logan’s Run sees the need not to merely end the story with the triumph of individuality by escaping the dystopian society, but to also tell youth how they should then live. While the Logan’s Run book merely concerned itself with the idea of people seeking the right not to have to die when they are told to, the film goes even further and sees that what is also needed is a return to traditional values.

Indeed, Logan’s Run is a film that seems like it is made by middle-aged conservatives who are unable understand what youth is rebelling about and believes that what they need is to forsake hedonism and make a return to traditional respect for one’s elders, for the sanctity of family and marriage and the American flag. There is an excruciating scene where Logan and Jessica stumble into Washington D.C., find the Lincoln Memorial, the ruins of the Capitol Building and a battered American flag and then realise the concepts of mother, father and lifelong commitment, as well as the joys of getting old. Eventually they surmise “People would stay together out of a feeling of love. They’d stay together, raise children and be remembered.” Logan’s Run is not unlike Damnation Alley (1977), which had people trekking across a holocaust landscape to finally arrive at an almost idyllically idealised vision of traditional Middle America.

In the title role, Michael York forcefully enunciates and elocutes every phrase as though emphasis equals emotion. Unfortunately, while York’s acting style is fine for a British period drama, he is not hero material and seems wimpy as Logan. Richard Jordan appears more like a thrill-seeking hippie than the film’s adversary. Jenny Agutter is, as always, lovely but the film fails to put her to any use, not even cursory romantic purposes. Peter Ustinov gives an embarrassingly bad performance, although the worst is the entirely vacant presence of Farrah Fawcett-Majors, appearing just before she was cast in Charlie’s Angels (1976-81) and became a 1970s poster pin-up sensation. Jerry Goldsmith turns in an uncustomarily bad score – full of electronics bleeps and bonks. Goldsmith is clearly trying to be experimental and achieve something futuristic but the results emerge as risible.

In the ensuing science-fiction boom that began the following year, the film was expanded into a tv series Logan’s Run (1977-8), which only lasted fourteen episodes. Logan was played by Gregory Harrison and Jessica by Heather Menzies, with both joined by an android Rem (Donald Moffat) as they moved through various situations on a weekly basis in their search for Sanctuary. The tv series was script-edited by D.C. Fontana, who had performed similar duties on Star Trek (1966-9). Although poorly regarded, the series nevertheless has some episodes – notably Harlan Ellison’s Crypt and David Gerrold’s Man Out of Time – that are better than this film. William F. Nolan (sans George Clayton Johnson) later wrote two sequels to the book – Logan’s World (1978) and Logan’s Search (1980). From around 2000, there have been persistent rumours of a remake with directors such as Bryan Singer, Tarsem Singh, Joseph Kosinski, Carl Rinsch and Nicholas Winding Refn all variously attached without the project ever having been greenlit. Logan’s Run is also spoofed in Free Enterprise (1998). The excellent In Time (2011) is also another variation on many of the ideas laid down in Logan’s Run.

Logan’s Run was directed by British director Michael Anderson. [Michael Anderson should not be confused with the dwarf actor of the same name best known for tv series such as Twin Peaks (1990-1) and Carnivale (2003-5)]. Anderson is a prolific genre director whose career has stretched five decades, beginning with hits in the 1950s such as The Dam Busters (1954) and Around the World in 80 Days (1956). Anderson has developed a bad reputation for having delivered almost universally terrible adaptations of otherwise fine science-fiction literary classics. Anderson’s other genre films include an adaptation of George Orwell’s 1984 (1956); The Shoes of the Fisherman (1968), a political thriller concerning a near-future Pope; Doc Savage, The Man of Bronze (1975) based on the pulp hero; the killer whale film Orca (1977); the psycho-thriller Dominique (1978); the tv mini-series adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles (1980); the thriller Bells/Murder by Phone/The Calling (1981) about killer telephone calls; the excruciating Adam and Eve softcore comedy Second Time Lucky (1984), one of the worst films ever made; the John Varley time travel film Millennium (1989); the tv movie remake of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1997); and The New Adventures of Pinocchio (1999).

Trailer here