UK. 1976.

Crew

Director – Nicolas Roeg, Screenplay – Paul Mayersberg, Based on the Novel by Walter Tevis, Producers – Michael Beeley & Barry Spikings, Photography – Anthony Richmond, Music Supervisor – John Phillips, Visual Effects – Peter S. Ellenshaw, Makeup Effects – Tom Burman, Art Direction – Brian Eatwell. Production Company – British Lion.

Cast

David Bowie (Thomas Jerome Newton), Candy Clark (Mary-Lou), Rip Torn (Nathan Bryce), Buck Henry (Oliver Farnsworth)

Plot

An alien from a dying planet comes to Earth to save his own world. Calling himself Thomas Jerome Newton, the alien makes his way across America, selling wedding rings to gain money. He then goes to lawyer Oliver Farnsworth and offers to sell patents on his advanced technology. With these, Newton accumulates vast wealth and then uses his money to build a spaceship, planning to return home with supplies of water for his people. However, the loneliness of life on Earth and its ways begin to corrupt and drive him insane.

At the time that he made The Man Who Fell to Earth, director Nicolas Roeg had emerged as an ambitious arthouse director. Roeg first appeared as co-director of the cultish Performance (1970), then moving onto Walkabout (1971) about English schoolchildren stranded in the Australian Outback; and the fascinating Don’t Look Now (1973), which is perhaps Roeg’s best film, a complex and enigmatic puzzle of a film about precognition.

In Don’t Look Now and the later Bad Timing (1980), Nicolas Roeg created films as densely layered tapestries of imagery that overlap and map onto other seemingly unconnected pieces of the film before eventually coalescing into a dense, stunning whole. The great failing of all Nicolas Roeg films is that they are caught halfway between a visual brilliance that few other directors ever manage to conceive and in being drowned by Roeg’s penchant for pretensions, often random visuals, cut-up editing and sexual obsessions. And this is no more than evident in The Man Who Fell to Earth.

The Man Who Fell to Earth could be the first impressionist science-fiction film. By comparison, the 1963 novel by Walter Tevis of The Hustler (1959) fame is much more straightforward and easy to understand. All the plotting in the film is elliptical – nothing is ever directly stated, we only gain a picture of the whole through the slow accumulation of images. The film is filled with pretentious affects. It often looks like someone has randomly edited together completely unrelated pieces of film – cuts between a Noh theatre performance or the progression of young students that Rip Torn beds. Roeg throws in random scenes like where David Bowie’s limo drives through the countryside and sees a pilgrim family, who suddenly vanish, followed by a reversed waterspout and light going up into the sky; or images of figures in white suits twirling in mid-air in slow motion with milk seemingly being thrown at them. None of these appear to relate to anything else in the film.

The film really slows down in the last third. Newton’s reunion with Mary-Lou, which seems like random out-takes from a drug orgy thrown together, drags on forever. The uncut international version of The Man Who Fell to Earth runs an often tedium-inducing 140 minutes, whereas the version seen in the US was cut by some twenty minutes.

All of Nicolas Roeg’s films seem to centre around an individual who is thrust into an alien culture – Edward Fox’s mobster hiding out in a counter-culture house in Performance, Jenny Agutter’s English schoolgirl thrust into the Australian Outback in Walkabout, Amanda Donohoe in the disillusioned desert island survival story of Castaway (1987) – where they undergo a process of disturbing, frequently sexual, self-discovery. In The Man Who Fell to Earth, Roeg seems fascinated as much by David Bowie’s alienness as he does by investigating the sexual predilections of the characters in the film.

Indeed, the characters in the film seem characterised by their sexual preferences – Buck Henry is gay; middle-aged professor Rip Torn obsessively beds eighteen year-olds who see him as a father figure; Candy Clark loves David Bowie with simple-minded wholeheartedness; and Bowie is simply asexual. For all that, it is never entirely clear what Nicolas Roeg is attempting to achieve with this. By comparison, there are no sex scenes in the book and there Mary Lou is a middle-aged housemaid.

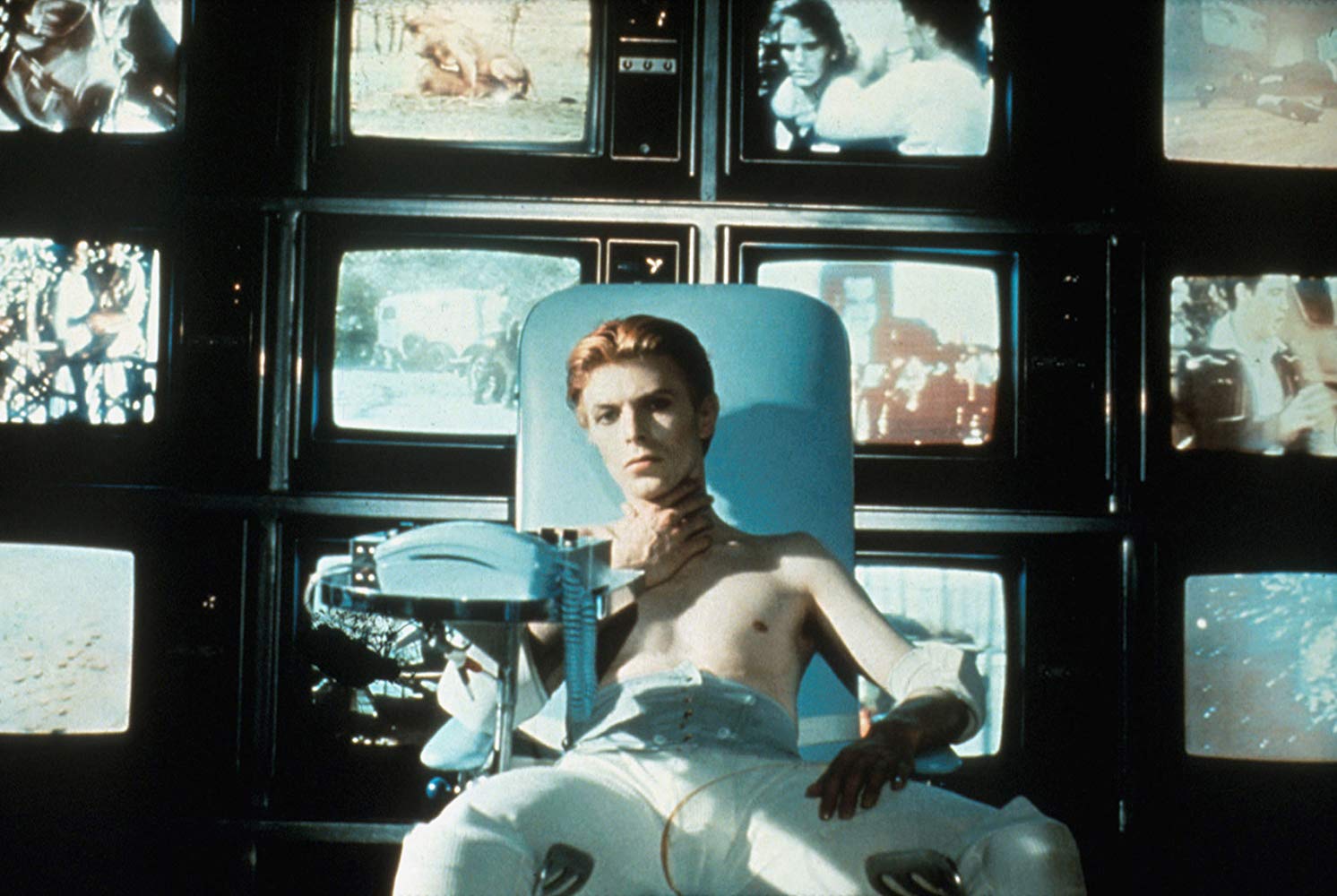

Yet amid all of this there are also some superb parts to The Man Who Fell to Earth. There is an eerily understated opening with David Bowie appearing in an Arizona small town, going into a pawnshop to sell what appears to be his wedding ring, before moving on and revealing to us dozens of identical wedding rings hidden inside his coat. Or the image of Bowie in front of a bank of tv screens screaming with information overload. In the film’s most striking scene, Bowie reveals his true self as a bald, cat-eyed alien to Candy Clark, only to have her pee herself in fright.

The Man Who Fell to Earth makes interesting comparison to both the alien invader films of the 1950s or the warm fuzzy aliens that emerged a few years later with Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and E.T. – The Extra-Terrestrial (1982). All of these involve confrontations between humanity and what is imagined to be The Other. 1950s alien invader cinema saw the universe as hostile and was symbolically about the American way of life as siege from the Cold War and the Nuclear Age; for Spielberg and the films of the 1980s, the universe held the unlimited recesses of the dreams of the baby boomer generation where The Other could come to enliven the boredom of life in suburbia or provide the enclosure of a broken family. By comparison in The Man Who Fell to Earth, The Other is frail and weak, while humanity is the aggressor. Clearly echoing a sense of late 1960s counter-culture disillusionment, David Bowie’s alien is fragile, broken by information overload, alcohol and the government conspiracy. The Man Who Fell to Earth could almost be a version of E.T. where instead of returning home E.T. just gives up, becomes disillusioned and turns into a wasted lush.

In the central role of Newton, Nicolas Roeg casts rock star David Bowie, having had great success casting another rock star Mick Jagger in his earlier Performance. David Bowie had gained superstardom a few years earlier with his glam rock stage persona as the bisexual alien Ziggy Stardust. By the point of The Man Who Fell to Earth, Bowie had developed a massive cocaine habit and was purportedly wired throughout shooting. Indeed, it was the Omnibus documentary Cracked Actor (1975) by Allen Yentob with the image of a coked-out Bowie drifting through L.A. in a limo seeming like an alien that made Nicolas Roeg pursue Bowie with the intent of casting him. With anorexic frame, pale skin, orange hair and mismatchingly coloured eyes, there is no-one more suited to play an alien than David Bowie. There are other fine performances from Candy Clark, Rip Torn and writer/director Buck Henry.

The film was later loosely remade as a pilot for a tv series, The Man Who Fell to Earth (1987) starring Lewis Smith in the David Bowie role. David Bowie later resurrected Newton as the central figure in Lazarus (2015), a stage musical based around his songs. The Man Who Fell to Earth (2022) was an eight episode tv mini-series sequel featuring Bill Nighy as the aging Thomas Jerome Newton and Chiwetel Ejiofor as a new alien arrived on Earth to find him.

Nicolas Roeg’s other genre films are:– the aforementioned Don’t Look Now (1973); the surrealist Dennis Potter collaboration Track 29 (1988); the wonderfully grotesque Roald Dahl children’s adaptation The Witches (1990); Cold Heaven (1991) where Mark Harmon mysteriously returns from the dead; and Puffball (2007) about withcraft and pregnancy. Roeg was also originally assigned to direct the remake of Flash Gordon (1980), which would have been most interesting to see.

Walter Tevis (1928-84) wrote other science-fiction novels. His other works adapted to the screen have been the acclaimed The Hustler (1963) and its sequel The Color of Money (1986) about pool hustlers, and the tv mini-series The Queen’s Gambit (2020) about a female chess champion.

Trailer here