USA. 1961.

Crew

Director – William Witney, Screenplay – Richard Matheson, Based on the Novels Master of the World and Robur the Conqueror by Jules Verne, Producer – James H. Nicholson, Photography – Gil Warrenton, Aerial Photography – Kay Norton, Music – Les Baxter, Photographic Effects – Butler-Glouner Inc & Ray Mercer, Special Effects – Tim Baar, Wah Chang & Gene Warren, Makeup – Fred Phillips, Production Design – Daniel Haller. Production Company – AIP.

Cast

Vincent Price (Robur), Charles Bronson (John Strock), David Frankham (Philip Evans), Henry Hull (Prudent), Mary Webster (Dorothy Prudent), Vitto Scotti (Topage)

Plot

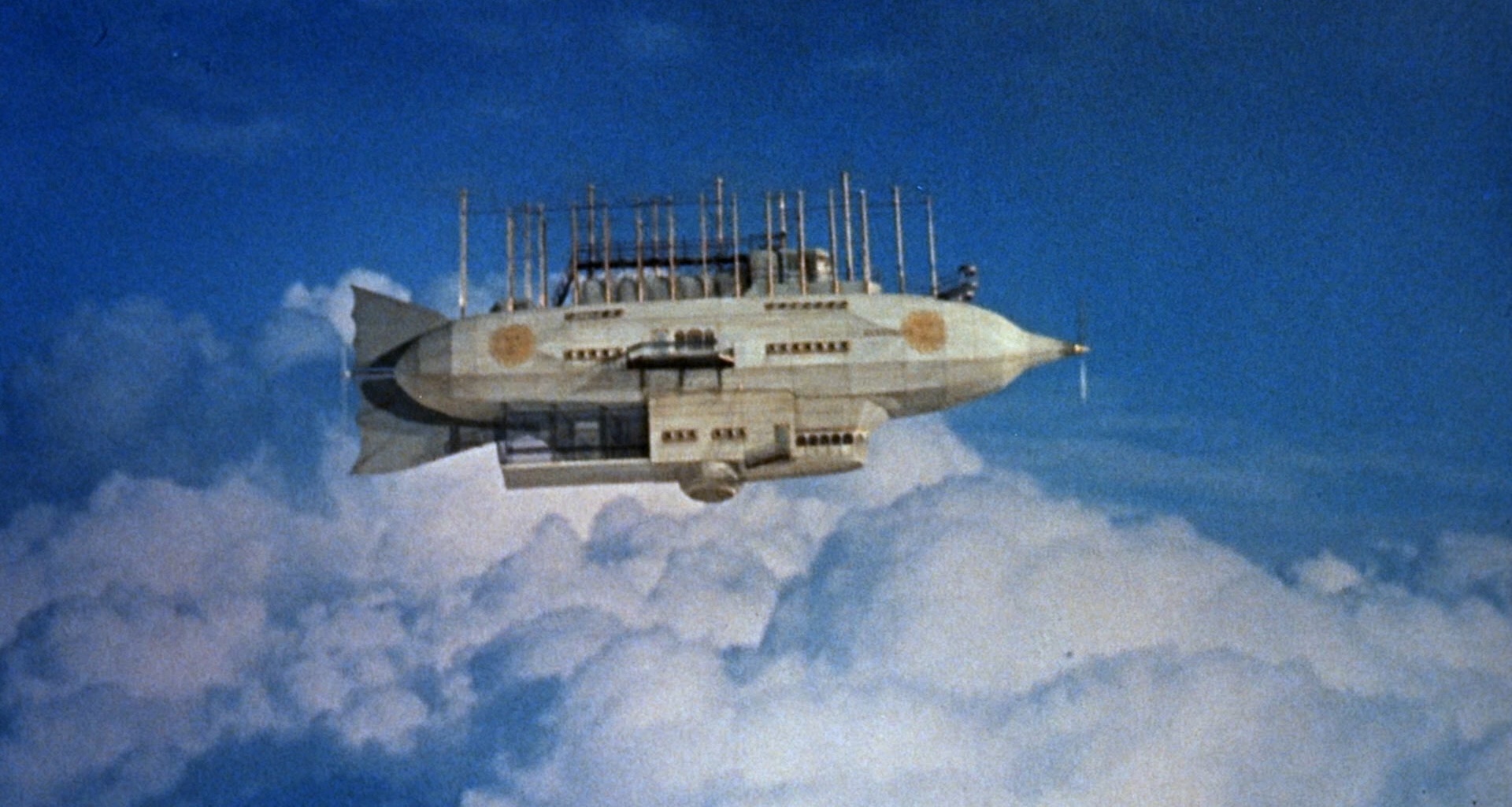

1868. Citizens of Morgantown, Pennsylvania, are startled when The Great Eyrie, the dormant volcano above the town, starts flashing and a sonorous voice announces the Judgement of the Lord is upon them. Geologist John Strock approaches the munitions magnate Prudent and his engineer Philip Evans and proposes the idea of an investigatory expedition by hot-air balloon. As they broach the volcano’s caldera, rockets are fired from inside, shooting their balloon down. They come around to find themselves aboard The Albatross, a giant propeller-driven airship built by the scientist Robur. The ‘Judgement of the Lord’ is revealed to merely be special effects created by Robur to keep the locals away while he was conducting repairs. As their journey gets underway, the group discover that Robur is a militant pacifist and is using The Albatross and its armaments to bomb the armies and naval warships of the world in order to force mankind to stop waging war.

Master of the World was one among a spate of Jules Verne adaptations that came out in the late 50s/early 60s. This mini-fad started after the success of Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954). 20,000 Leagues outfitted Captain Nemo’s submarine in Victorian finery, brass grillwork and steel boilerplates, creating a distinctive proto-Steampunk look that was copied by most of the subsequent entries. This was followed by MGM’s equally successful Academy Award-winning Around the World in 80 Days (1956), which approached Jules Verne’s adventure story as a colourful jape filled with gaudy costumery, overacting guest stars and villains.

These were followed by a spate of other Verne adaptations, including the likes of The Fabulous World of Jules Verne (1958), From the Earth to the Moon (1958), Journey to the Center of the Earth (1959), Mysterious Island (1961), Valley of the Dragons (1961), Five Weeks in a Balloon (1962), In Search of the Castaways (1962), The Stolen Airship (1967), On the Comet (1970) and The Light at the Edge of the World (1971), as well as original works climbing aboard the bandwagon such as Jules Verne’s Rocket to the Moon/Those Fantastic Flying Fools (1967) and Captain Nemo and the Underwater City (1969).

Master of the World comes from American International Pictures (AIP), a studio that had had success in the 1950s with a heap of low-budget teen and monster/science-fiction films with entertainingly cheesy titles. Into the 1960s, AIP began to expand beyond B-budget films with the success of Roger Corman’s series of Edgar Allan Poe adaptations. Master of the World comes from legendary genre screenwriter Richard Matheson, who had written most of Corman’s Poe films and other classic works like The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), Duel (1971), The Night Stalker (1972) and several novels including I Am Legend (1954). Director William Witney was mostly known for his work on numerous Westerns and serials, including classics like Adventures of Captain Marvel (1941), The Perils of Nyoka (1942) and Spy Smasher (1942).

Richard Matheson principally adapts Jules Verne’s novel Robur the Conqueror/Clipper of the Clouds (1886), while borrowing the title and the central character of John Strock from Jules Verne’s second-to-last book, the Robur sequel Master of the World (1905). I somewhat heretically think that in playing around with Verne, Richard Matheson has in fact created a more interesting story than Verne himself did. Robur the Conqueror lacks the idealistic conflicts that the film has – Robur was the inventor of an airship but the people taken aboard were members of a society that were attempting to build an airship whom Robur considered rivals and abducted to demonstrate his superiority. Of course, Matheson’s turning of Robur into a militant pacifist now makes him another version of Captain Nemo ramming warships in his submarine and as a result many people dismissed Master of the World as just a copy of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

However, Richard Matheson’s treatment is a too interesting to dismiss Master of the World as merely a 20,000 Leagues copycat. Especially interesting are the characters played by David Frankham and a young Charles Bronson – Frankham initially comes as the standard romantic hero of the piece, which is something that Matheson then skilfully undermines to turn him into a dangerous hothead while still giving him what would be classic heroic motives, while the real hero of the piece is allowed to emerge in Bronson who has a utilitarian disregard for gentlemanly honour and proper morals.

There are some very well written confrontations between Vincent Price’s Robur and munitions manufacturer Henry Hull where Richard Matheson stands off and refuses to allow the ideologies of either to appear totally valid. It is almost as though Matheson has determined to write a debate that vigorously questioned the ideals that lay behind Captain Nemo’s pacifism in 20,000 Leagues.

In terms of production values, Master of the World gives the impression of trying to be an A-budget production on a B-budget. Most of the budget seems to have been blown on the superlative Albatross model – the shots of it cruising through the clouds and across the oceans are splendid. Unfortunately, other effects are shoddy in comparison, notably the use of stock footage from other films. With an entrepreneurial anachronism of about four hundred years, London is represented by footage taken from the Laurence Olivier production of Henry V (1944), a feature that many commentators often alight upon and use to ridicule the otherwise worthwhile film, and there are other unidentified sequences of an Egyptian battle. The size of the airship and the distances it is supposed to be flying also seem to vary wildly – what is said to be twenty feet above a river seems more like 300 feet, and a valley that supposedly has no turning room looks half-a-mile wide.

There is also an irritable comic-bookishness to the film, as was the tone throughout many of these Jules Verne adaptations. Vincent Price’s fruity hamming is a performance without realism, more suited to the exaggerated posturings of stage comedy. There is much in the way of the burlesque playing – all eye-rolling and puffed-up cheeks – common to actors of the 60s like Terry-Thomas and Gert Frobe in the characters of a comic-foil cook and the initial way that Henry Hull comes across. There is also an absurdly jaunty score that jumps along with the unflappable jollity of a summer pops season, determined to drown out all dialogue and play on indifferently no matter what the on-screen action may require.

Richard Matheson’s other genre scripts are:– The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957) based on his own novel, Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe adaptations The House of Usher/The Fall of the House of Usher (1960), Pit and the Pendulum (1961), Tales of Terror (1962) and The Raven (1963), the occult film Night of the Eagle/Burn, Witch, Burn (1961), the mortician’s comedy The Comedy of Terrors (1963), The Last Man on Earth (1964) based on his novel I Am Legend, the Hammer psycho-thriller The Fanatic/Die, Die, My Darling (1965), the classic Hammer occult film The Devil Rides Out/The Devil’s Bride (1968), the historical biopic De Sade (1969), Steven Spielberg’s first film Duel (1971), The Night Stalker (1972) and The Night Strangler (1973) tv movies, the haunted house film The Legend of Hell House (1973), the tv adaptation of Dracula (1974), the tv movies Scream of the Wolf (1974), The Stranger Within (1974), Trilogy of Terror (1975), Dead of Night (1977) and The Strange Possession of Mrs. Oliver (1977), the tv adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles (1980), the time travel romance Somewhere in Time (1980) from his own novel, Jaws 3-D (1983), Twilight Zone – The Movie (1983), and numerous classic episodes of The Twilight Zone, Thriller and Star Trek. Works based on his novels and stories are The Omega Man (1971) from his I Am Legend, the afterlife fantasy What Dreams May Come (1998), the fine ghost story Stir of Echoes (1999), I Am Legend (2007), The Box (2009) and Real Steel (2011).

Trailer here