USA/Australia. 1999.

Crew

Directors/Screenplay – The Wachowski Brothers, Producer – Joel Silver, Photography – Bill Pope, Music – Don Davis, Visual Effects Supervisor – John Gaeta, Visual Effects – Animal Logic Film, Bullet Time, D Film Services & Manex Visual Effects, Miniature Supervisor – Tom Davies, Special Effects Supervisors – Steve Courtley & Brian Cox, Makeup Effects – Bob McCarron, Animatronic Prosthetics – Makeup Effects Studio (Supervisors – Paul Katte & Nick Nicolaou), Production Design – Owen Paterson, Conceptual Design – Geoffrey Darrow, Kung Fu Coordinator – Yuen Wo Ping. Production Company – Warners/Village Roadshow/Groucho II Productions/Silver Pictures.

Cast

Keanu Reeves (Thomas ‘Neo’ Anderson), Laurence Fishburne (Morpheus), Carrie-Anne Moss (Trinity), Hugo Weaving (Agent Smith), Joe Pantoliano (Cypher), Gloria Foster (The Oracle), Marcus Chong (Tank), Belinda McClory (Switch), Anthony Ray Parker (Dozer), Matt Doran (Mouse), Julian Arahanga (Apoc)

Plot

Thomas Anderson is a corporate employee by day but by night leads a secret existence as a hacker by the handle of Neo. He has spent two years trying to track down the enigmatic super-hacker Morpheus. As law enforcement officials with superhuman abilities attempt to apprehend Neo, Morpheus comes to his aid. Morpheus then offers Neo the chance to see the true nature of reality. Neo accepts and Morpheus leads him into a future where he commands a group of rebels aboard the vessel Nebuchednezzar hidden near the centre of the earth. In this future, the Earth has been destroyed in a war between humanity and AIs. The remnants of humanity have been made into a cattle race who serve to house and power the AIs and are kept trapped in a Virtual Reality simulation where they are led to believe that nothing has changed over the present-day world. As Morpheus trains Neo in how to develop martial arts skills and the ability to master the virtual environment, they are hunted within the simulation by AIs posing as law enforcement agents, while outside they face traitors among Morpheus’s crew. Gradually, Neo comes to understand his predestined role as The One, the saviour who will deliver humanity from its virtual enslavement.

The Matrix created a revolution when it came out. It seemingly appeared from nowhere in the summer of 1999 and afterwards cinema was not quite the same again. It was the same thing as happened in May of 1977 when George Lucas released Star Wars (1977). Many parallels can be drawn between The Matrix and Star Wars – in both cases, they were films made by creators with a distinctive vision that came fuelled by a deep immersion in fannish cinema of past eras; in both cases, the creators had greater ambitions than merely placing their ideas in one film but were necessitated in having to doing so by the dictates of commercial cinema; and in both cases, the filmmakers created a stylistic and special effects revolution that ended up changing the look of science-fiction cinema. You might draw further thematic parallels – the stories are vaguely the same, wherein a neophyte is drawn into an epic struggle of right against wrong in a greater world beyond his horizon where he must find mystical fighting abilities within himself in order to fulfil his destiny.

The Virtual Reality theme had caught the attention of a number of filmmakers beginning in the 1990s but had only been milked by a number of bad movies – think of the likes of The Lawnmower Man (1992) and its ghastly sequel Lawnmower Man 2: Beyond Cyberspace (1996), Mindwarp (1992), Ghost in the Machine (1993), Arcade (1994) and Virtuosity (1995). Up to this point, the Virtual Reality topic had been thematically dominated by a handful of limited clichés that ranged either between Luddhite hysteria about VR supplanting reality or engaged in tiresome games of what is real and what is illusion. In fact, one strains to think of a single decent Virtual Reality movie to have been made prior to this – the tv series VR.5 (1995) was not too bad but that is all. [There was the superb Spanish-made Open Your Eyes (1997), but that was not released internationally until after The Matrix came out]. The Virtual Reality theme had practically cried out for an intelligent and worthwhile treatment.

One interesting and curious fact is the Doctor Who serial The Deadly Assassin (1976), which contains one of the very first depictions of Virtual Reality on film, where Tom Baker’s Doctor enters a VR simulation known as The Matrix, which is made up of a series of united minds and ends up with a fight over whose ability to control the scenario wins.

1999 suddenly proved to be a gateshed year with a host of Virtual Reality movies entering the fray all at once – with The Thirteenth Floor (1999) and David Cronenberg’s disappointing eXistenZ (1999) all appearing within the space of a couple of months of one another, along with Chris Carter’s short-lived tv series Harsh Realm (1999), even a Christian fundamentalist film about the Devil seducing people by Virtual Reality in Revelation (1999) and the very obscure Dreamtrips (1999). The Matrix was the first of these to be released and entered the field with a sophistication of ideas that was not unakin to the sobriety and intelligence that the likes of Star Trek (1966-9) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) brought to science-fiction after a decade of B movies and the likes of Lost in Space (1965-8) and Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (1964-8) when they first came out.

The Matrix comes from brothers Larry and Andy Wachowski (who bill themselves onscreen as The Wachowski Brothers). The Wachowski Brothers began as comic-book artists, wrote the screenplay for the dire Assassins (1996) and then had considerable critical success with their directorial debut Bound (1996), an excellent thriller that zigzagged through an unusually adept series of twists and turns while taking the distinctive step of making its two protagonists lesbian lovers. Its freshness immediately signalled the Wachowski Brothers as major new talents. Needless to say, the two did not disappoint with The Matrix.

With The Matrix, The Wachowski Brothers happily set aside Virtual Reality clichés and leap in with a story of considerable audacity. The Matrix is one of the few cinematic science-fiction stories that can compare to literary equivalents. Without a doubt, it was the masterpiece we were waiting for to emerge out of the Virtual Reality bombast. At times, the plot is not unreminiscent of the ignored sf masterpiece Dark City (1998). Both The Matrix and Dark City are conceptual breakthrough stories set in a world that bears many close similarities to our own but which is instead an artifice maintained as a facade for an unwitting populace by sinister non-human, sunglasses-clad figures that can bend reality. In both films, the protagonist is someone who has the same reality-warping abilities as the non-humans and comes to thus see through and ultimately bend for the better the reality he is trapped in. Even further, The Matrix ended up using some of the sets that were built for Dark City.

The Wachowski Brothers offer up the mind-bogglingly paranoid Philip K. Dick-ian idea that not only is all of reality is a simulation but that it is also a sinister Virtual Reality illusion and moreover a realm where one can become a Zen master and manipulate the illusion. They offer up Zen-like epigrams: “Don’t try to bend the spoon – that’s impossible. Instead only try to realise the truth.” “What truth?” “There is no spoon. Then you’ll see that it is not the spoon that bends, only yourself.”

There are even oblique postmodern jokes – a disc is hidden in a hollowed copy of Jean Baudrillard’s book Simulacra and Simulation (1994). (Baudrillard could almost be considered the philosophical father of The Matrix in his view that reality is unknowable and has been conceptually colonised by others’ ideas). There are certainly many questions that the film leaves unanswered – What is The One? Who is The Oracle? What is The Prophecy? How come things inside the simulation are predestined and foretold? However, the sophistication of the ideas that the film plays with is dazzling.

As much as anything, The Matrix stands out for the Wachowski Brothers’ magpie collage of stylistic influences. Everything from obvious connections to cult writer William Gibson (and even more so Australian science-fiction writer Greg Egan) to the extraordinary displays of martial arts and pyrotechnic balletics that have been directly borrowed from the Hong Kong action film (to the extent of recruiting the HK stunt supervisor and sometimes director Yuen Wo Ping. There is even a Jackie Chan in-joke – one of the martial arts programs being loaded in the training simulation is a Drunken Boxing one), to comic-book superheroics, the dark, visually gloomy look of the graphic novel, the plot arc of The Terminator (1984), allusions to Alfred Hitchcock, The Wizard of Oz (1939) and Alice in Wonderland (1865). All of this is shot through with substantive meditations on predestination and what becomes a Zen guide to virtual martial arts.

The Wachowski Brothers have consolidated these influences not into a pastiche but a unique stylistic synthesis of their own. While most lesser Western action directors around the same time had just discovered and seemed hell-bent on imitating Hong Kong cinema’s fast-paced revved-up action ballet, the Wachowski Brothers did far more unique things with it.

Seeing The Matrix for the first time, the opening scene with the sinister pursuing agents conducting superhuman flights and leaps, followed by the sequence where Carrie-Anne Moss suddenly conducts a slow motion mid-air twirl was something that left one sitting wondering what they had just seen. Elsewhere, protagonists conduct startling and impossible mid-air twists and backflips, superheroic leaps of tall buildings and punches through pillars, while ducking bullets in slow-motion, amidst which the Wachowski Brothers’ camera sinuously weaves and either fast-forwards or pauses the combatants in mid-air in ways that we have never seen melee take place on screen before. The effect is breathtaking (and one that was quickly copied by a host of imitators).

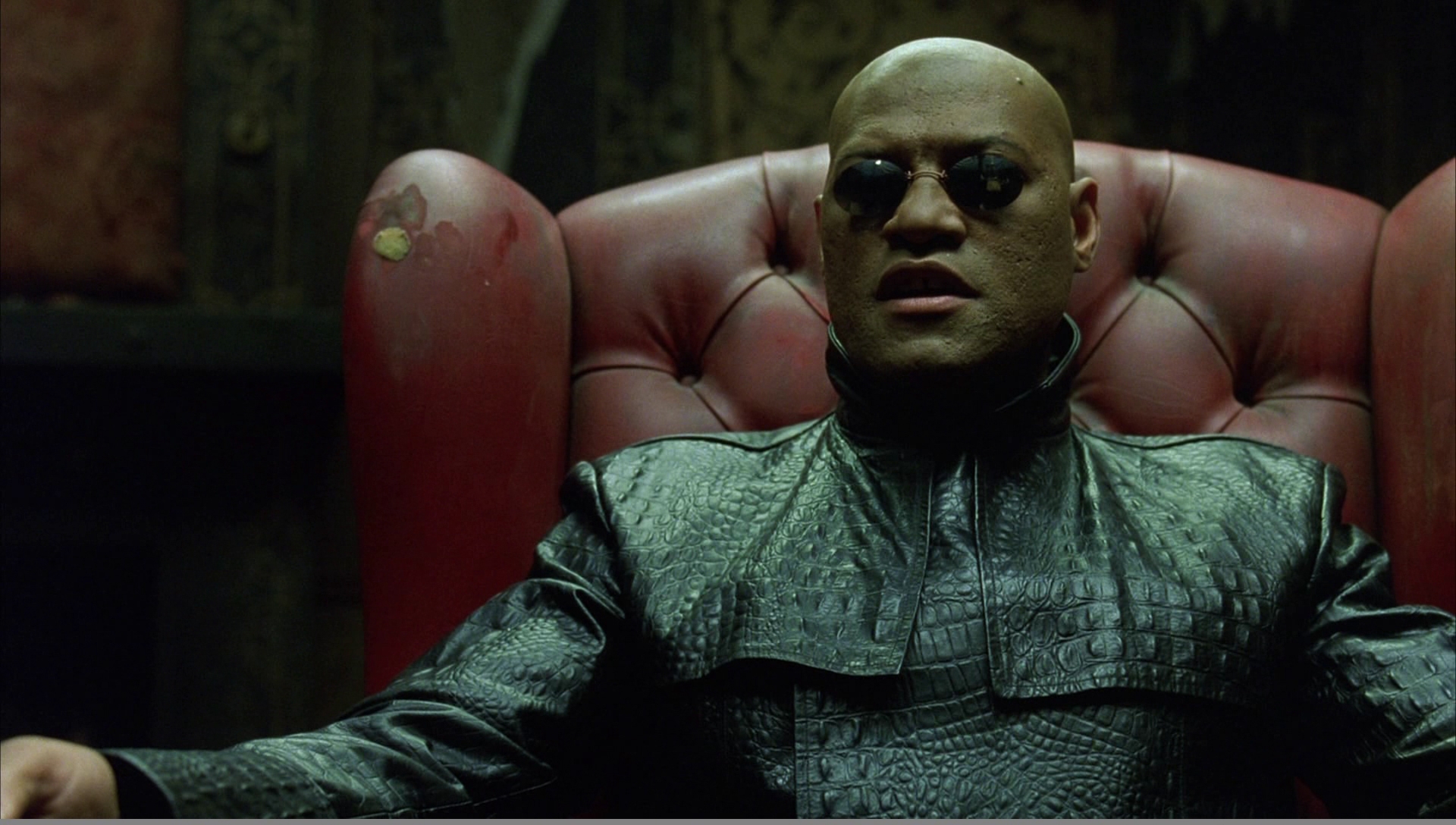

The Wachowski Brothers even manage to distract one from Keanu Reeves’ habitual non-acting – largely by placing him inside an absorbing story and limiting his acting to a series of impressively cool poses while decked out in black raincoat and designer shades. (If nothing else, The Matrix is a film of sublime cool. It is not acted so much as it is posed, from Keanu Reeves raven-like in all black coat and shades, Laurence Fishburne in legless shades and everyone else it seems perpetually clad in leather, vinyl, PVC and shades). Laurence Fishburne and Carrie-Ann Moss are both very good, although the show is stolen by Aussie Hugo Weaving as the lead AI agent who captivates with his spookily inhumane accent and bent for icily detached remonstrations on the sadness of the human condition.

At nearly two-and-a-half hours, The Matrix may be overlong but the uniqueness and brilliance of the story is something that keeps one compulsively engaged. This is one of the few films one wanted to return and see again immediately just so they could drink in more of its ideas. It is also rare to see a genre story so intelligently driven become as big a box-office success and the cult hit as this has. Indeed, it is one occasion where an audience’s fascination with the film outstripped the distributor’s expectations of it – it was released in the US without much build-up, yet went to the No 1 box-office spot in its first week.

The Wachowski Brothers and most of the cast made two sequels that were shot back-to-back, The Matrix Reloaded (2003) and The Matrix Revolutions (2003), although most agree that these disappoint on the level of ideas raised here. At the same time, the Wachowskis also authorised The Animatrix (2003), a feature-length compilation of nine animated shorts set in and around the world of The Matrix. Larry/Lana Wachowski subsequently returned to direct/co-write The Matrix Resurrections (2021).

The Wachowski Brothers subsequently went on to direct the live-action adaptation of the animated tv series Speed Racer (2008), the cross-historical Cloud Atlas (2012) and the space opera Jupiter Ascending (2015), as well as create, write, produce and direct much of the tv series Sense8 (2015-8) about eight individuals around the world who are mentally connected. They also wrote and produced the adaptation of the Alan Moore graphic novel V for Vendetta (2006) and then produced Ninja Assassin (2009), both for their assistant director James McTeigue. They also purportedly uncreditedly helped write additional material for the troubled The Invasion (2007). From 2012, they are credited as just The Wachowskis due to Larry (and later Andy)’s sex change to become respectively Lana and Lilly..

The Matrix‘s martial arts battles were quickly copied by other films and parodied in Scary Movie (2000), Cats & Dogs (2001), Shrek (2001), Kung Pow: Enter the Fist (2002), Austin Powers in Goldmember (2002) and Without a Paddle (2004). The Agent Smiths also cameo as guest villains in The Lego Batman Movie (2017), while we see the film invaded by Looney Tunes in Space Jam: A New Legacy (2021).

(Winner in this site’s Top 10 Films of 1999 list. Winner for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay, Nominee for Best Actress (Carrie-Ann Moss), Best Supporting Actor (Hugo Weaving) at this site’s Best of 1999 Awards. No. 5 on the SF, Horror & Fantasy Box-Office Top 10 of 1999 list).

Trailer here