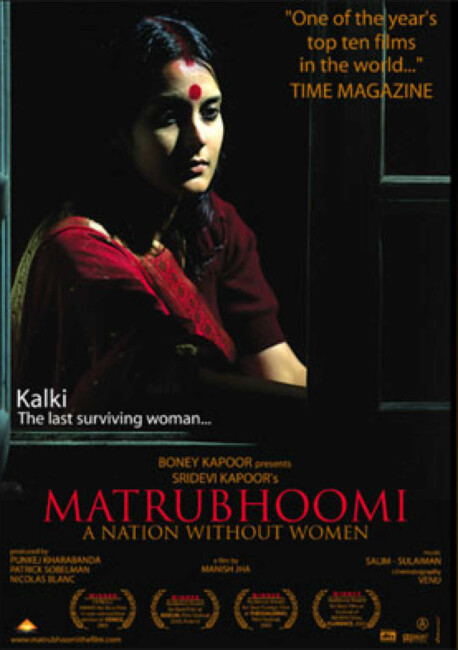

(Matrubhoomi)

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Manish Jha, Producers – Nicolas Blanc, Punkej Kharabanda & Patrick Sobelman, Photography – Venu, Music – Salim-Sulaiman, Art Direction – Wasiq Khan. Production Company – SMG/Ex-Nihilo.

Cast

Sudhir Pandey (Ramcharan), Tulip Joshi (Kalki), Sooshant Singh (Sooraj), Piyush Mishra (Jaganath), Pankaj Jha (Rakesh), Deepak Kumar Bandhu (Shailesh), Sanjay Kumar (Brijesh), Shrivas Nydu (Lokesh), Rohitash Gaud (Prateb), Chittaranjan Giri (Pappu), Farook Sarkari (Gajendra), Rajesh Jais (Princess Pinky), Amin Gazi (Sukha)

Plot

India sometime in the near future. As a result of too many infant girls being killed at birth by families not wanting to pay dowries, there is a drastic countrywide shortage of women. In one village, the men try to cope by watching drag performers and pornographic movies, even having sex with animals. The local priest Jaganath then comes across a girl Kalki in the woods. The wealthy Ramcharan offers her father Prateb 500,000 rupees to buy her as bride for his five sons. After the marriage, each of the sons agrees to spend one night of the week each with her, with the father having her on the remaining two. However, Kalki soon cannot stand the way they treat her – all except the handsome youngest son Sooraj whom she comes to love. Seeing her attraction to Sooraj, the other brothers jealously murder him. She tries to escape but is recaptured and chained up in the barn. There the locals, angry over the murders that the family have conducted, sneak in and take turns raping her in revenge.

India has the single largest filmmaking industry of any country in the world. What is noticeable in running this site is the conspicuous lack of Bollywood fantastic films reviewed. This does not represent any particular prejudice against Bollywood cinema or India on the author’s part, or the fact that India does not make any sf, horror or fantasy films (it does sporadically), rather the simple lack of Indian films that make it to general accessibility in English-speaking countries. Only a miniscule amount of the total output of Bollywood is ever screened in Western arthouse cinemas and when Indian films are released to video they can rarely ever be found outside of ethnic-specific video stores. One wonders why – after all, other international cinemas such as Japan and Hong Kong enjoy healthy general releases around the rest of the world. Perhaps it is that Indian cinema lacks the same sort of culty crossover appeal to Western audiences that both Japanese and Hong Kongese films do. Anyway, long overdue, here at least is the first Bollywood fantastical film review to grace this site.

A Nation Without Women is nominally a science-fiction film, although it is debatable if it has been conceived in a genre framework. What it has been made more as is a work of social warning, taking on the issue of female infanticide in India by families not wishing to be burdened with crippling and excessive marriage dowries. This throws it into the company of works like Born in Flames (1983) – works of sf prognostication that are more interested in hammering a political point about the present than in exploring the ideology of a future state. The end of the film, for example, comes with a title card that notes that there have been an estimated 35 million dowry-related infant murders in India.

Certainly, considered as science-fiction, A Nation Without Women has a fundamentally implausible set-up. It strains credibility that a society would keep murdering its women to the extent of not even noticing that there weren’t any left, or doing anything about stopping this practice for the sake of reproductive survival. What becomes even more implausible is the simple question – where are all the remaining women? We see only a single woman throughout, however we also have men in their twenties and thirties, even a couple of boys in their teens. This leads one to ask the natural question – who gave birth to all the young people we see? Even if we accept that no new women have been born, the mothers of the people we see would surely still be alive somewhere, even if they were in their forties and fifties. You keep asking other questions – could the solution not have been found in importing brides from other countries that do not engage in this cultural slaughter?

That said, despite a fundamentally implausible basic scenario, A Nation Without Women does a fine job of exploring the social reaction to such a situation – with images that show men reduced to tears at watching a badly copied porn video, seeking relief with barnyard animals, reacting to a crossdresser on stage as though he/she were a stripper, one father attempting to marry a boy off disguised as a woman. Although, while it does dance around the subject, the one thing the film never mentions is homosexuality. Surely in such a women-depleted society, homosexuality would be rampant, or at the very least the society would have created strong taboos about such. The real issue here, one suspects, is that such subjects are regarded as taboo on the heavily censored Indian cinema screens, which do not permit on-screen nudity or even the portrayal of kissing, for instance. That said, the film certainly does push some taboo lines in other areas depicting (or at least suggesting if not exactly showing) sex with both humans and moreover animals, men masturbating to porn videos, rape, and with a degree of general vulgarity. Clearly this is a film that sets out with the intent of pushing the Indian screen taboo line as far as it can.

Ultimately though, A Nation Without Women is a film that loses a good deal of impact shown to Western audiences such as at this film festival screening in Wellington, New Zealand. It is a film that needs to be seen within its social context for its true impact to be felt, one suspects. Outside of Hindi culture, some of the more subtle intonations are not always apparent. For example, the father’s protest about the oldest son not getting married first is clearly something that has no relevance in Western culture, while what is intended as a comic moment where the daughter’s father’s expresses surprise at being offered money for his daughter instead of being expected to pay a dowry is a joke that slips by the audience. I, for instance, did not understand until near the end that the young boy in the household who has the running gag about peeing in guest’s glasses of sherbet was not the youngest son of the family as assumed but actually an Untouchable servant.

The strongest parts of the film are those depicting the treatment of the single woman in the film by the men. The montage scenes showing her ice-cold indifference as the various husbands turn up on each day of the week is well achieved, while other tiny vignettes that depict her progressive degradation – her father’s abandonment of her with the offer of more money, being tied up in the barn alongside the animals, the villagers sneaking in to take turns raping her – create a strong and disturbing degree of sympathy for the treatment of women by Indian society. Indeed, rather than a sense of outrage about the problem of dowry-related infanticide, what the film leaves one with is a shock about the abuse of women by men at every level of Indian society. Even though made by a male director, the film has a quite radical feminist sympathy. There are only two men in the film that can in any way be regarded as sympathetic – the brother Sooraj whom Kalki comes to love and the young servant boy – and the only response from the rest of the men is to murder them.

Full film available here