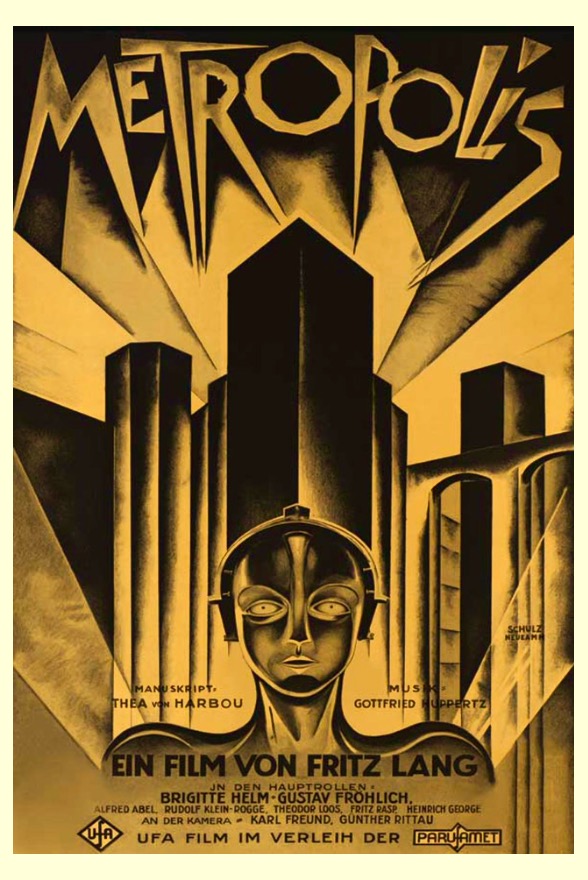

Crew

Director – Fritz Lang, Screenplay – Fritz Lang & Thea von Harbou, Producer – Erich Pommer, Photography (b&w) – Karl Freund & Gunther Rittau, Visual Effects – Eugen Shuftan, Production Design – Otto Hunte, Erich Kettlehut & Karl Vollbrecht. Production Company – Ufa.

Cast

Gustav Froelich (Freder), Brigitte Helm (Maria), Alfred Abel (Joh Fredersen), Rudolf Klein-Rogge (Rotwang), Fritz Rasp (The Thin Man), Theodor Loos (Josaphat), Heinrich George (Grot), Erwin Biswanger (Georgy 1811)

Plot

A vast future city is divided between its proletariat who slave at the machines in the city’s depths and the administrators who live in palatial comfort high in the city’s towers. Freder, son of the city’s leader Joh Fredersen, is struck by the beautiful Maria when she leads a delegation of children into the upper towers. He follows her down into the city depths where she stirs revolt among the workers over the conditions they endure. Swayed by Maria, Freder implores his father to make changes. Instead, his father goes to the scientist Rotwang and gets him to build a robot double of Maria to corrupt the worker’s sympathies. Rotwang seethes over the fact that Fredersen stole his beloved Hel away from him and sees this as an opportunity for revenge. Using the robot Maria, Fredersen has her seduce the workers to rebel and bring the city smashing down.

Metropolis is maybe the most famous silent film ever made. It is certainly the most enduring, one of the few that is still screened today and one that manages to amaze audiences as much today as it did when it was first screened. It was the work of Fritz Lang, one of the most visionary of all silent directors.

Born in Austria in 1890, Lang was the son of an architect. Expected to follow his father’s footsteps, Lang instead chose to become an artist. After wandering through Asia, Lang returned to serve in World War I, where he rose to the rank of lieutenant and was wounded three times. Following the War, Lang started work at the Decla Bioscop film studios, initially as a writer, where he quickly progressed through the ranks to become a director, premiering with the lost The Half-Caste (1919) and then catching attention with the two-part adventure film The Spiders (1919). Lang first broached fantasy subjects with Destiny (1921), a multi-episodic cross-historical drama about an incarnate Death. Lang reached his heights with Dr Mabuse, The Gambler (1922), his classic about a criminal mastermind ruthlessly manipulating a decadent Berlin, and the two-part Niebelungen saga Siegfried (1924) and Kriemhild’s Revenge (1924), a colossally scaled interpretation of the Teutonic legend. It is however Metropolis that Fritz Lang will be forever remembered for.

The period from around 1913 and in particular from 1919 to the early 1930s was an unparalleled era of fantastic cinema in Germany. Although there were antecedents, the floodgate was opened by the Expressionist classic The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1919). The era went onto produce other fantastic epics like F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922) and Faust (1926), Paul Leni’s Waxworks (1924) and several versions of Alraune, The Golem and The Student of Prague, among others. Few other eras of fantastic cinema have produced such epic visions, either architecturally or stylistically.

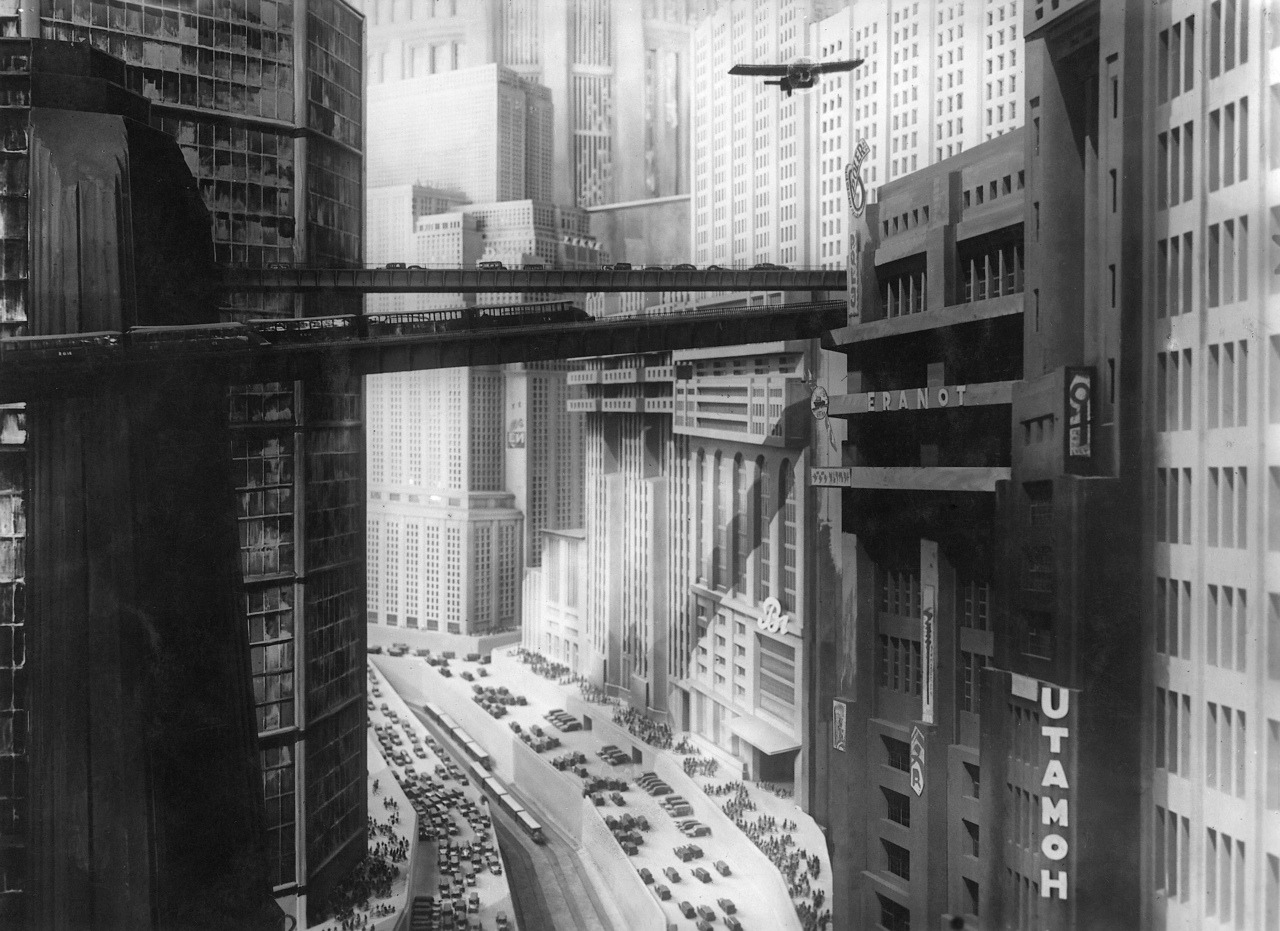

What strikes most about German fantastic films is almost invariably their sets. They were marvels of architectural fantasy and came built on a colossal scale. Metropolis, for instance, was the most expensive film ever made in the world at the time – costing 7 million marks (which would be around $200 million today). It took the combined resources of two studios and nearly bankrupted them when it received a middling box-office reception.

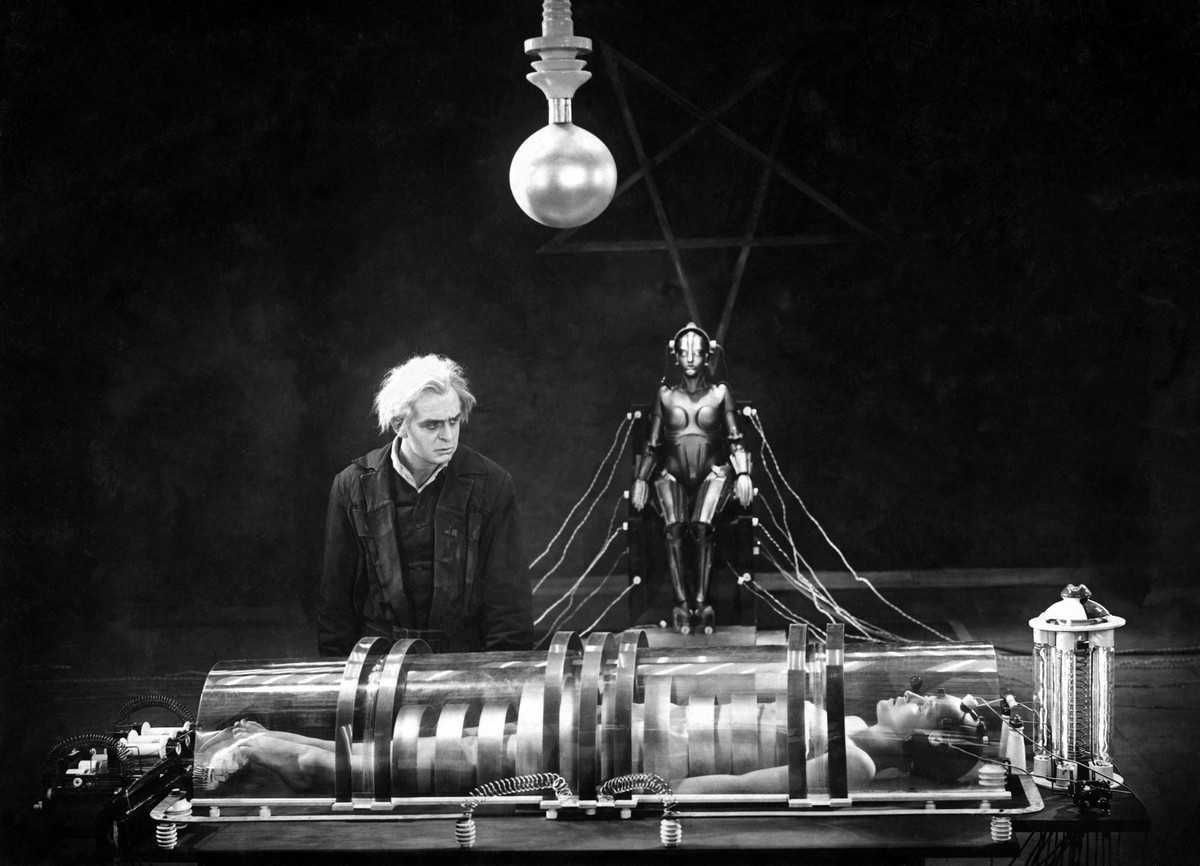

The scale of Metropolis is staggering. Some of the set pieces rank among the great images of fantastic cinema – Moloch devouring the workers, Freder working the arms of the clock, the recounting of the Tower of Babel story, the robot Maria’s erotic dance, and especially the sequence where Rotwang brings the robot to life. Lang wields big crowds (some 37,000 extras) into stylised pantomimes. His gigantic multi-layered sets overwhelm the eye. Part of the reason for the expense of these films was that all the sets would be built in forced perspective – larger up close, smaller further away – to make them seem much bigger than they were. (This is the reason why the camera rarely moves within a scene but usually stays in master shot and then cuts to closeups and medium angles – if you change the angle from which you look at a forced perspective set, the illusion vanishes).

The striking thing about such extravagant fantasies was also the social backdrop against which they were made. Following World War I and the establishment of the short-lived Weimar Republic, Germany was thrown into financial chaos by massive war reparations levied by the League of Nations and was virtually ruined by massive over-inflation. That somebody in the midst of this could lavish the time and money to make such an extravagant fantasy is remarkable.

Its reputation aside, Metropolis is a lunatic film. The plotting is a naive mishmash, especially when it comes to the politics. It was a function of the times, more than any real comment on the Marxist revolution. This was the era of Germany’s Weimar Republic, which was as naive in its democratic outlook as this film’s thinking. Dialogue is as flowery as the hammy contorted acting – it is hard to imagine any trade union leader today getting anywhere with an epithet like “The heart must mediate between the hands and the brain” [or the more accurately translated “The mediator between head and hands must be the heart!” in the 2010 restored version] on their placard. All of Metropolis‘s effect lies in the visuals, not its story or sociology.

Moreover, Metropolis is an oddly schizophrenic film. It seems to be born out two differing visions of Germany that on one side glorifies its mythic Mediaeval past and on the other stretches towards a vision of a modern industrial Utopia. This dividing line runs right through all German silent fantastic cinema. The Cabinet of Dr Caligari was an exaggerated fantasy that takes place inside the distorted world of a madman and employed the Expressionist stylism of art and theatre – all twisted, angular sets and heavy shadows. By its nature, it was anti-realism, full of exaggerated movements that were intended as outward expressions of inner states of mind. It was the first film to take cinema away from realism and a literalistic depiction of events.

Caligari‘s success gave birth to huge studio-based spectacles that drew upon the same stylised Expressionism in their design. A number of these films returned to a mythologised historic past and took themselves from Teutonic or Mediaeval mythology – Lang’s Niebelungen saga, Murnau’s Faust, Paul Wegener’s Golem films. Many other films of the era such as Nosferatu, Lang’s own Destiny, The Student of Prague (1913), The Hands of Orlac (1924) and The Student of Prague (1926) seem shrouded in Gothic superstition and Mediaeval worldviews. If one wants an idea just how strong these Mediaeval notions struck in the German mindset at the time, look nor further than Adolf Hitler and the Nazis’ mystic obsession with the Knights Templar and deification of the Teutonic heroism of Richard Wagner. Many of these films – Homunculus (1916), the Golem films, the various versions of Alraune – also centre around the Gothic notion of human-like artificial creations that go amok.

Silent German fantastique cinema seems caught on one hand between this backward-looking reverence of mythic heroism and the Gothic Mediaeval worldview, and a drive toward industrial modernity on the other. At the same time as all this was happening, both the Weimar Republic and, following that, Nazi Germany was shucking all remnants of the Kaiser’s empire and becoming a relentlessly modern nation. Many films of the later half of the 1920s and beyond celebrate epic feats of engineering and human triumph – Lang’s Woman in the Moon (1929), F.P.1 Does Not Answer (1932), The Tunnel (1933), Gold (1934). Indeed, you can draw parallel between Lang’s vast city of the future and Nazi architect Albert Speer’s plans for the architectural rebuilding of Berlin as an shining monument of modern industrialism, or between Lang’s crafting of crowds here and the way that Leni Riefenstahl later used the crafting of huge crowds as political propaganda for Adolf Hitler in films like The Triumph of the Will (1934) and The Olympiad (1938).

Metropolis seems caught between these two strands of thought – the fearful occlusion of the Mediaeval Gothic on one hand and the bold optimism of the New Germany reaching toward marvels of technology on the other. For all its celebration as a visionary science-fiction film, Metropolis is fearful, Gothic and anti-science in nature. Rotwang is a sorcerer rather than a scientist and even comes with a pentagram above his door and in his lab, while social progress is seen in terms of lurid images of Biblical enslavement – the machine as Moloch, epic engineering feats in terms of the hubris of the Tower of Babel.

Metropolis is certainly confused in terms of its motives and messages. You are not even sure what all the Biblical imagery is meant to represent. Traditionally, for example, The Tower of Babel is about visionary idolatry; here it becomes a heavy-handed symbol for oppressed workers. It is not clear why Fredersen inspires his own workers to revolt and tear down his own city (although the restored versions make clear that this was Rotwang subverting Fredersen’s orders because Fredersen stole his wife Hel and that Fredersen went along with out of a desire to teach the workers a lesson). You can even debate if Metropolis is as much on the side of the exploited working classes as it would appear to be. Notedly, it is the mad scientist, not the industrialist, who is responsible for upsetting the balance of labour classes and is the one who is punished for his actions, while the industrialist benevolently restores the status quo.

The working class masses seem docile and only move about in a downcast group without any individuality and require the machinations of an evil robot version of the film’s saintly heroine in order to be inspired to revolution – the implication seeming to be that disgruntled workers are only stirred to revolution by malevolent influence. (In other Fritz Lang films such as Dr Mabuse and Spies (1927), people are often seen as weak and easily manipulated by strong dominant leaders). The end is not a resolution so much as it is a restoration of the status quo with promise of more communication. A classical Marxist would almost certainly blame the exploited condition of the workers on the industrialist and merely regard the mad scientist as their lackey. Lang’s Woman in the Moon is a film that is much more forward thinking, less anti-progress. Metropolis rallies against the inhumanity of the Industrial Revolution in sentimental Marxist cliches and is fearful of progress, while Woman in the Moon is a film that celebrates the great vision that built the cities we see here and more. Fritz Lang later disliked the ending and said he did not think it worked, although was never clear about his reasons for thinking so.

For all its muddiness of thinking, Metropolis is an astonishing film. It is a visual triumph despite the silliness of the plot and the naivete of its politics. Alfred Abel gives a coldly and autocratically controlled performance as Fredersen and Brigitte Helm makes an extraordinary change between virginal beatitude and gleeful malice, the latter none more so than the nightclub dance scene, daring for its time and still carrying a highly erotic charge today. Rudolf Klein-Rogge’s mad scientist is all the over-the-top posturing that was considered to represent madness and villainy during the silent era.

Alas, the Metropolis seen on screens (at least up until the 2000s) was an incomplete vision. For the film’s American release in 1927, nearly a third of the reels (an hour’s worth of screen time) were removed in order to make the film’s approximate 2½ hour running time more palatable for audiences and to eliminate any possible Communist messages. Fritz Lang was vocal about the butchering of the film and once said that “Metropolis no longer exists.” The search for a complete version of Metropolis became regarded as akin to a quest for the Holy Grail.

First of the restoration attempts was the Giorgio Moroder version of Metropolis, released in 1984. Moroder, the producer of several of Donna Summer’s disco hits and Top 10 crossovers from films like Flashdance (1983) and Cat People (1982), and an Oscar winning composer with the score for Midnight Express (1978), scoured the world in search of prints. Moroder succeeded in tracking down material never before shown, inserting stills where he could not find footage and re-released the film. The order of some scenes was rearranged the way Moroder believed the late Fritz Lang would have wanted them, based on screenwriter Thea Von Harbou’s novelisation. Unfortunately, the new material in Moroder’s version adds up to less than a minute’s worth of time. Some scenes where the worker that Freder replaces goes to the Yoshiwara nightclub and the scenes of the robot Maria enticing men there are shown only in stills. There is also a brief scene of Rotwang climbing a pile of vehicle wrecks, blindly thinking that Maria is Hel. A few stills are also added of cityscapes and the Garden of Pleasure.

The Giorgio Moroder version tightens some scenes editorially, particularly in the replacement of intertitle cards with subtitles, allowing much slicker pacing. (The subtitles now refer to the automaton as a robot, a term that was not in popular use in 1927). Moroder also adds sound effects and a music score. The sound effects add a great deal – the robot’s unveiling, heralded by the dull clank of its footsteps, or the roar as the crowds revolt proves startling. There is an effective electronic score – the pop songs are not that memorable but work well enough in the context. One other highly impressive effect is the tinting of footage. The film is still principally in black-and-white alternated with sepia tone but some scenes come with beautifully rotoscoped-in bubbling potions, boiling coloured clouds and glowing neon signs. It is a surprisingly effective move and one that for all the sacrilege cried at the time only succeeds in enhancing the film.

An extensive digital restoration project was conducted by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung foundation and the German federal film archive Bundesarchiv Filmarchiv beginning in 1998 and premiering in 2001. This adds some 40 minutes of missing material. Subsequently in 2008, a near-complete print of Metropolis was found in Buenos Aires. This was combined with the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung 2001 restoration and released in 2010, making the most complete version of Metropolis ever seen in the English language. About all that is missing from this version is eight minutes worth of scenes. The Buenos Aires print is unfortunately in 16mm and poor condition, meaning that some of the scenes look grainy and are in different aspect ratio to the others. However, the result has been patched together and demonstrates at last the vision that Fritz Lang intended. This combined version restores a great many missing sections – the scenes with Freder frolicking at the Eternal Gardens prior to Maria’s appearance with the children; Freder’s offer of help to Josaphat, the worker fired by his father; the scenes where the worker Gyorgy 1811 strays into the Yoshiwara nightclub; the back explanation about Joh Fredersen’s stealing Hel away from Rotwang (including a magnificent scene where Fredersen uncovers a giant-sized bust of her in Rotwang’s lab) and Rotwang’s swearing of vengeance; all of the scenes with The Thin Man who is assigned by Fredersen to follow Freder and how he tries to drive both Josaphat and Gyorgy 1811 away; more scenes during the flooding where Freder and the human Maria try to save a group of children.

This allows a much fuller sense of what the story was about. People’s actions and scenes no longer tend to exist in a vacuum – we understand Rotwang’s vengeance and why Fredersen wants the cities torn down, while the religious allegories are no longer just pretty imagery. On the other hand, you have sympathy with the US editors as their cut removed some of the less interesting material and subplots while retaining all the visionary elements with the robot and the city of the future. The Moroder print made the missing Yoshiwara nightclub material seem far more exotic than it appears in actuality, for instance. What also becomes apparent is just how much the original story was ripe in religious allegory – the stories of the Tower of Babel, allusions to Maria as The Whore of Babylon, the saintly Maria surrounded by crosses, Freder consulting The Book of Revelations, lost scenes of preachers, the dance of the Seven Deadly Sins – almost making it one of the Biblical morality plays that were popular on film during the day.

Metropolis has often been mentioned as a remake, although nobody has yet tried to do so. However, the Japanese anime Metropolis (2001) loosely reworks the basics and is a dazzling film in its own right. Echoes of Metropolis can be found in science-fiction films everywhere. Mad scientists of the 1930s owe much to Metropolis, with the creation of Maria being strongly echoed in the reanimation scenes in Frankenstein (1931). Rotwang also casts his shadow over Peter Sellers’ essayal of the title role in Dr Strangelove or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), while the Maria android clearly influenced the design of C3P0 in Star Wars (1977). The vision of the city of the future was copied and echoed in films such as High Treason (1929), Just Imagine (1930), Blade Runner (1982), Brazil (1982), Dark City (1998) and Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (2004).

Fritz Lang’s other films of genre interest are:– Destiny (1921) wherein Death incarnates two lovers throughout various historical periods; Dr Mabuse, The Gambler (1922) concerning a ruthless criminal mastermind; the two-part Niebelungen saga, Siegfried (1924) and Kriemhild’s Revenge (1924) based on the Teutonic myths; Woman in the Moon (1929), a realistic attempt to portray a Moon landing; M (1931), a thriller concerning the hunt for a child killer; The Testament of Dr Mabuse (1933); the afterlife fantasy Liliom (1933); the film noir psychological thriller Secret Beyond the Door (1948); and a further Dr Mabuse sequel The 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960). Lang also wrote the script for Plague of Florence (1919), an adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Masque of the Red Death (1842)

Trailer here

Full restored film available here:-