(Metoroporisu)

Japan. 2001.

Crew

Director – Rintaro, Screenplay – Katsuhiro Otomo, Based on the Manga by Osamu Tezuka, Music – Toshiyuki Honda, Animation Studio – Madhouse Productions, Animation Supervisors – Shigeo Akahori, Shigeru Fujita, Yasuhiro Nakura & Kunihiko Sakurai, Character Design – Nakura, Art Directior/CG Art Director – Shuichi Hirata. Production Company – Metropolis Committee.

Plot

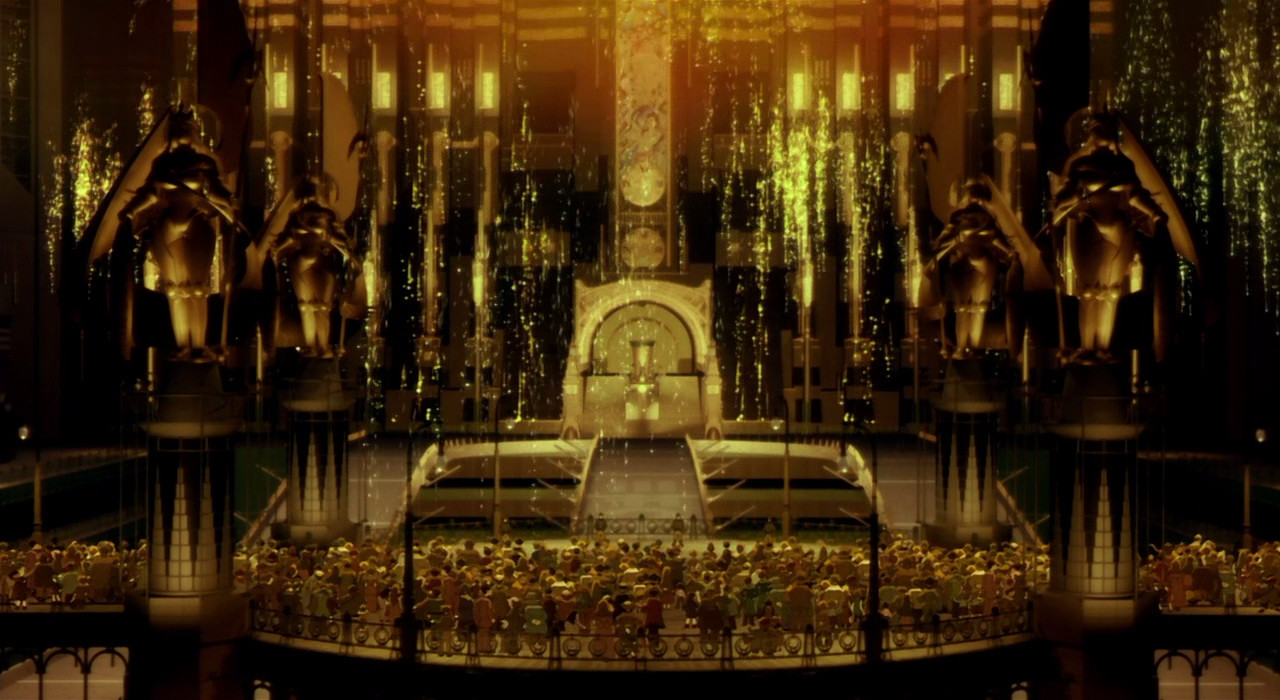

In the future city of Metropolis, the leader Duke Red builds the city’s most powerful new edifice The Ziggurat. The Duke’s most loyal follower Rock makes the discovery that Dr Laughton has created a human-like android, the girl Tima, to sit on the throne of The Ziggurat alongside Duke Red. There being considerable anti-robot prejudice among the people in the city, Rock decides that Tima must be destroyed to protect the Duke and so kills Laughton and blows the laboratory up. However, Tima is thrown free in the explosion and is found in the sewers by police detective Kenichi. Kenichi begins to educate Tima’s blank mind and the two fall in love. They then have to deal with the pursuing Rock, as well as masses that are rising up in anti-robot riots after having been stirred up by the scheming President Boon who wants to bring Duke Red down.

Metropolis was one of the most acclaimed animes of the early 2000s. Its arrival was highly touted, even though it was not a huge success in Japan when released. Of course, what drew everybody’s attention was the collaboration of names on the credits. First, there was Katsuhiro Otomo, director of Akira (1988), the cult name in anime. Katsuhiro Otomo’s shadow seems to cast itself over every anime made since Akira, whether as some creative consultant or in films that draw their influence from Akira‘s scenes of transcendental mass destruction and epic mind-stretching scale, even though Otomo has rarely returned to take up the director’s chair again.

In the director’s chair itself, there was Rintaro, sometimes known as Taro Rin, the director of works like Galaxy Express 999 (1979) and X (1996). And everything was based on a manga by the late comic-book artist Osamu Tezuka, director, writer and producer of various Japanese films like Alakazam the Great (1961) and Space Firebird 2772 (1979) and the creator of the original manga that led to tv series like Astro Boy (1963) and Kimba the White Lion (1965-7).

Metropolis shares its title with Fritz Lang’s silent classic Metropolis (1927), although is actually based on Osamu Tezuka’s manga written back in 1949 (which was written when Tezuka had only seen a single still from the still). Nevertheless, the film has definitely been construed as a modern version of Lang’s Metropolis – in both films, there is a city master who lives in a tower far above the masses toiling in the city’s bowels. There is an android girl constructed by a mad scientist on orders from the master of the city and a hero from the upper echelons who falls in love with the girl. And the masses naturally rise up in rebellion against the robots and the city comes falling down at the climax.

Rintaro’s Metropolis even retains the symbolic comparison Fritz Lang made between the towers of the city and the Tower of Babel. Of course, this is also a post-Blade Runner (1982), post-Akira, post-William Gibson Metropolis that has been updated to the world of the internet, anime-styled transcendental mass destruction and the densely crowded future cityscapes of Cyberpunk imagery.

What is utterly stunning about Metropolis is its backgrounds. The film constructs a unique retro look for the future, as though the clock had been wound back and it was a vision of Cyberpunk/Blade Runner that had been made in the grand era of Art Deco. It is a film where the background is almost a character in itself. The artistic detail that has gone into this is amazing – teeming street scenes, terraces filled with dozens of tiny individually milling characters. Or how each building or section of the background seems to come lit and painted a different colour, or the scenes of the ruined city in the aftermath of the climax where it seems as though the animation artists were determined to use every colour of the rainbow all at once within each frame. There are times the density of the visual design almost becomes overwhelming – like where the Japanese detective arrives at the police office and the giant window behind the desk is filled by a stunningly detailed whale swimming past, followed by an equally exquisitely detailed dirigible, images that have such crystalline clarity that the pure awe of them distracts from what the actual exchange in the foreground is about.

Somewhat at odds with such densely beautiful backgrounds comes the depiction of the characters with classically anime-styled large over-exaggerated eyes. The effect is akin to an episode of Sailor Moon (1995-2000) having been crossbred with Blade Runner – the detective hero Kenichi, for example, looks as though he is in his pre-teens. Consummate with the stylised 40s era retro-future look, Metropolis also has a swing score (which features director Rintaro on bass clarinet). This is none the more effective than at the climax where the requisite mass destruction comes eccentrically yet hauntingly scored to Don Gibson’s I Can’t Stop Loving You (1957).

The plot is complex with numerous different factions running about where it is not always clear what is happening. Nevertheless, Metropolis is an extraordinary film, one where Rintaro’s work has made an extraordinary leap from his previous middle-of-the-road light anime pop films to create a genre landmark.

Rintaro’s other films are:- Galaxy Express 999 (1979), Adieu, Galaxy Express 999 (1981), Harmageddon (1983), one episode of the anthology Neo-Tokyo (1987), Doomed Megalopolis (1991), X (1996), the 13-part OVA mini-series Space Pirate Captain Harlock: The Endless Odyssey (2002) and Yona Yona Penguin (2009).

(Winner for Best Production Design at this site’s Best of 2001 Awards).

Trailer here