USA. 2000.

Crew

Director – Brian De Palma, Screenplay – Jim Thomas, John Thomas & Graham Yost, Story – Jim Thomas, John Thomas & Lowell Cannon, Producer – Tom Jacobson, Photography – Stephen H. Burum, Music – Ennio Morricone, Visual Effects Supervisors – John Knoll & Hoyt Yeatman, Visual Effects – CIS Hollywood, DreamQuest Images & Industrial Light and Magic & Tippet Studio, Alien Character Design Supervisor – Jeff Mann, Makeup Effects – KNB EFX Group, Production Design – Ed Verreaux. Production Company – Jacobson Co/Touchstone.

Cast

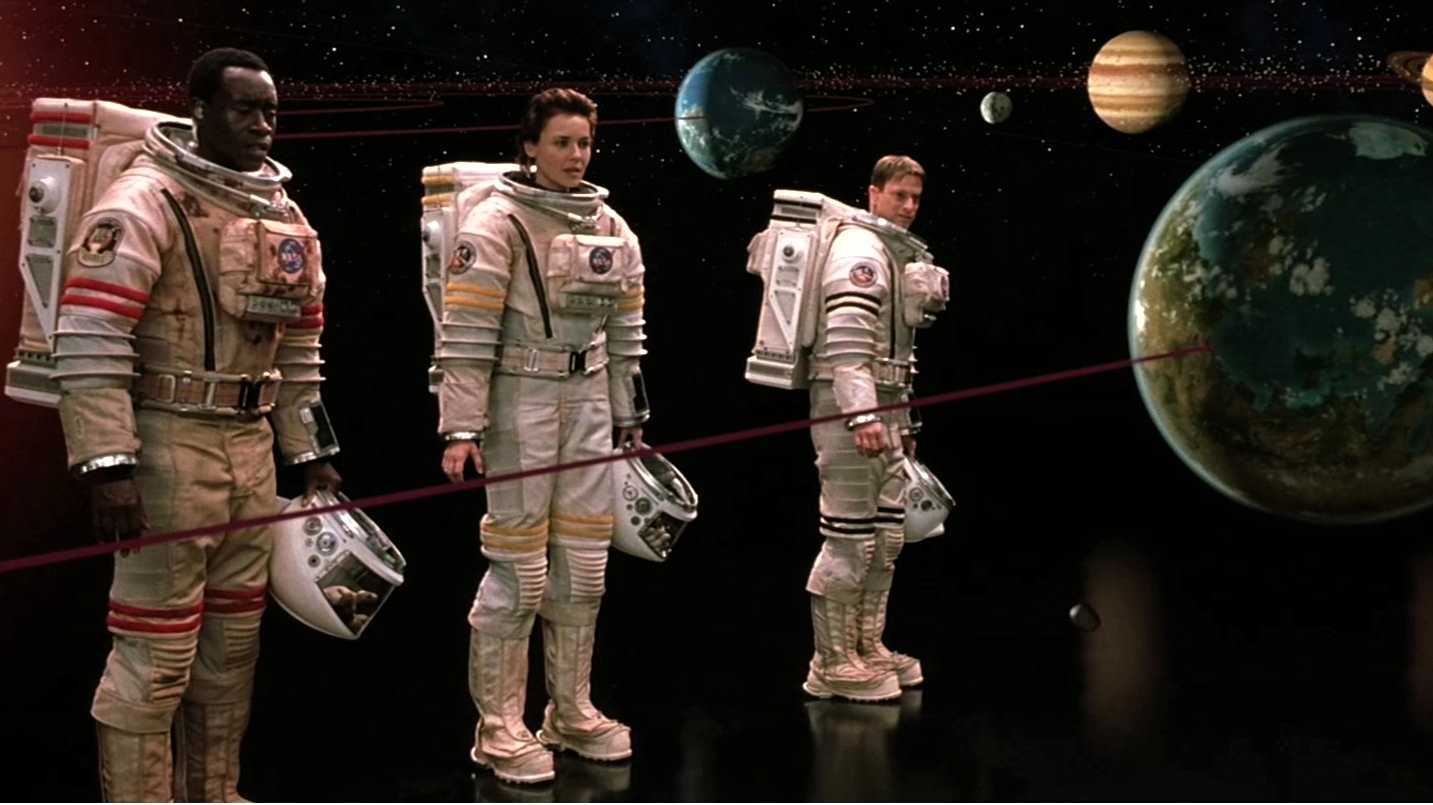

Gary Sinise (Jim McConnell), Tim Robbins (Woody Blake), Don Cheadle (Luc Goddard), Connie Nielsen (Terri Blake), Jerry O’Connell (Phil Ohlmeyer), Armin Mueller-Stahl (Ray), Jill Teed (Renee Cote), Peter Outerbridge (Sergei Kirov), Kim Delaney (Maggie McConnell)

Plot

In the year 2020, Mars 1 becomes the first manned Mars landing. The crew discover a giant structure in the sand. However, as they attempt to investigate, they are obliterated by a sudden sandstorm. At Mission Control, it is believed there may be one survivor and so a rescue effort is launched. However, the rescue ship is destroyed in an accident following a micro-meteorite storm. The crew survive and make a landing, finding the sole survivor who has spent a year living inside a greenhouse. From there they investigate the anomaly, a giant face-shaped structure, the decoding of which may reveal the secrets of the beginnings of life on Earth.

In the mid-1990s, there was a huge boom in Mars-themed science-fiction publishing. First there was Kim Stanley Robinson’s epical trilogy – Red Mars (1992), Green Mars (1994) and Blue Mars (1996) – arguably the most dazzling work of science-fiction writing, social projection and hard science in the 1990s. This was followed all more or less at once by Ben Bova’s Mars (1992), Greg Bear’s Moving Mars (1993) and Larry Niven’s Rainbow Mars (1999). Much of this fascination came out of the discovery in 1996 of the Mars rock and the furore over the possibility of life on Mars, as well as the intense worldwide fascination with the Mars lander photos a couple of years later.

Mission to Mars was the first of a host of serious scientifically credible Mars films to reach the big screen all at once – the same period also included the video-released Escape from Mars (1999), Red Planet (2000), John Carpenter’s delayed Ghosts of Mars (2001) and with James Cameron also having announced a Mars film project around this time that never came to fruition. None of these were regarded as particularly successful by the critical press or general public – although this author would beg consideration otherwise – and it was not until The Martian (2015) a few years later that we had a definitive Mars movie.

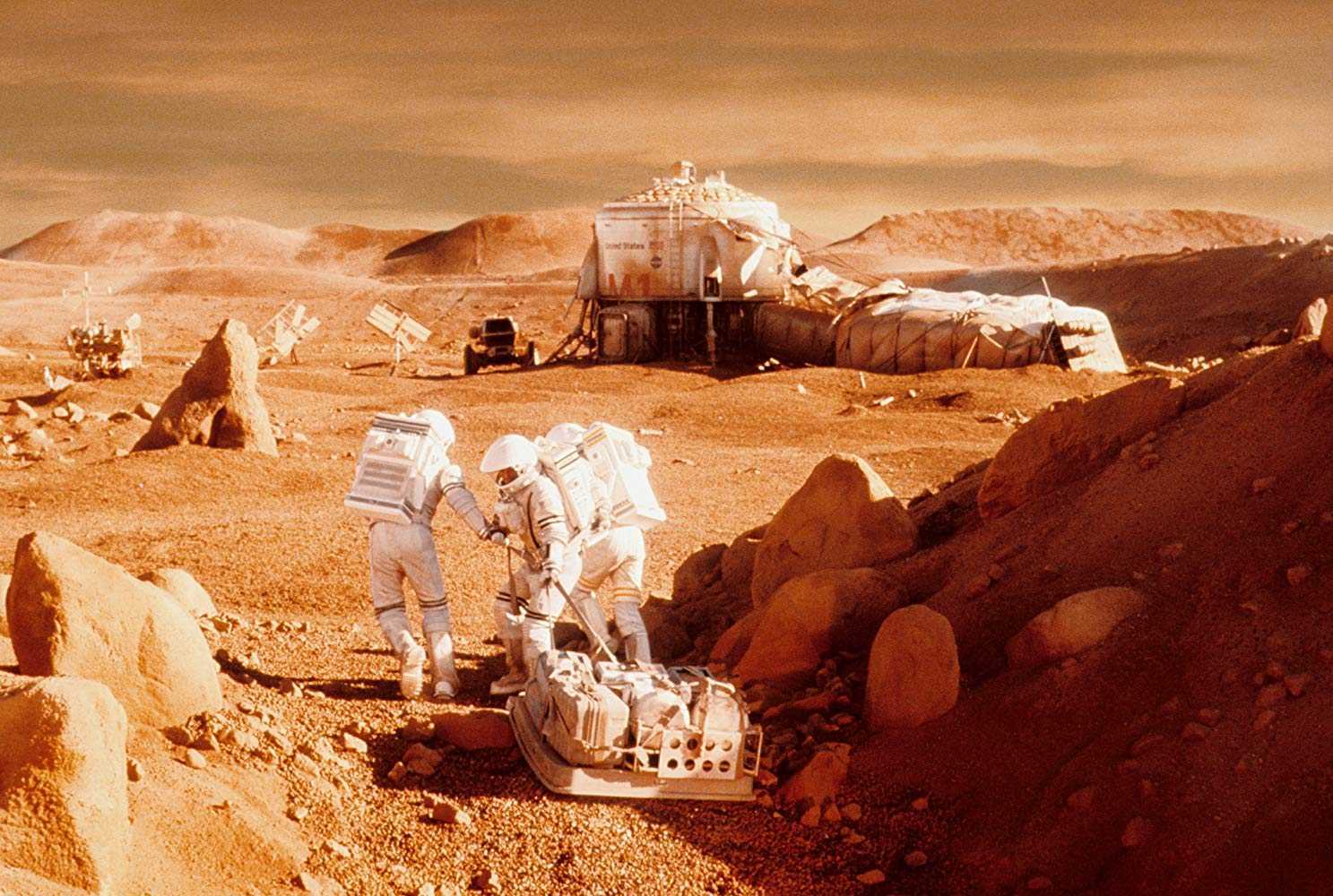

Mission to Mars is immediately a different Mars film to anything that had gone before. Previously, Mars had been a lurid potboiler locale for movies such as Aelita (1924), Flight to Mars (1951), The Angry Red Planet (1959) and the cauldron out of which emerged the aliens in films such as The War of the Worlds (1953), Invaders from Mars (1953), Devil Girl from Mars (1954), The Day Mars Invaded Earth (1962) and Mars Needs Women (1966). The most thematically substantial Mars treatments up this point had been Robinson Crusoe on Mars (1964), a well-worthwhile but even in its time scientifically unfeasible survivalist story; the dreary tv mini-series adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles (1980) – and even then Bradbury’s vision was knowingly a scientifically anachronistic one; or else Capricorn One (1978) about a faked Mars landing. There was the promising Mars (1996) but this turned out to be no more than a mediocre action movie where the title location was of no relevance. Mission to Mars feels like the first film to be set on a real Mars wherein the filmmakers have gone and exactingly recreated Mars in a studio based directly on the lander photos.

Mission to Mars was directed by Brian De Palma. Brian De Palma first obtained genre attention in the 1970s with a directorially dazzling series of genre films – Sisters (1973), The Phantom of the Paradise (1974), Obsession (1976), Carrie (1976), The Fury (1978), Dressed to Kill (1980), Blow Out (1981) and Body Double (1984). In the latter half of the 1980s and 1990s, De Palma less interestingly dropped back to being a director for hire. His best films have been his most personal ones – gangster films such as Scarface (1983) and Carlito’s Way (1993) – but his other commercial entries – the Vietnam War film Casualties of War (1987), the notorious The Bonfire of the Vanities (1990) and Snake Eyes (1998) – were strangely unaffecting. De Palma had huge hits with The Untouchables (1987) and Mission: Impossible (1996) but in retrospect these only consist of individual set-pieces of stylistic panache and fail to hold together in terms of plot. The question with Mission to Mars is is a stylist such as Brian De Palma capable of subsuming his showy directorial style to conduct a big-budget science-fiction film that draws upon top drawer special effects to carry it, rather than individual directorial stamp.

The answer is surprisingly, yes. Here the big-budget hard-science sf film and Brian De Palma’s stylistic showmanship merge with surprising congruence. There is an unobtrusive opening sequence where one realises that De Palma is doing one of his old tricks of shooting a scene in a single shot – something that he notedly did in the first twenty minutes of Snake Eyes – at a barbecue that goes on for several minutes and takes place within two single shots, each of which moves between several different vignettes and mini-dramas occurring at once.

The hard science scenes allow De Palma some dazzling set-ups – he is not merely content to do a single sequence a la Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and show astronauts travelling around a rotating treadmill but cuts across the cross-section of the wheel to show various of the crew nonchalantly at work, exercising, relaxing and so on at different angles from one another around the circumference of the cylinder. [In the documentary De Palma (2015), De Palma admits that he became fed up with the lengthiness of the effects process and this was the reason he subsequently quit making films in Hollywood].

The script for Mission to Mars comes from brothers Jim and John Thomas who wrote Predator (1987) and Predator 2 (1990) and Graham Yost. Graham Yost had previously established himself as a writer of brainless action vehicles such as Speed (1994), Broken Arrow (1995) and Hard Rain (1998). Where Yost showed his mettle was as scripter and supervising producer of the fabulous tv series about the American space programme From the Earth to the Moon (1997) where he demonstrated an impressive ability to chart out the vicissitudes of hard science while also making it sound dramatically interesting.

Here Graham Yost and the Thomases have taken the time to make the science believable and real. They have clearly researched the greenhouse habitats, the orbital velocities, docking procedures and extra-vehicular maneuvers and know what they are talking about. (Regrettably though, most of the cast give the impression they have no idea what they are talking about – especially Tim Robbins who looks like he is stoned). While most of the trained monkey critics ended up slamming Mission to Mars for its technical gobble-de-gook, it makes perfect and enthralling sense as a work of hard science.

Moreover, the script does not merely highlight realistic science but uses it as the basis of enthralling suspense. There is an extended sequence in the middle with the ship being punctured by micro-meteorites, a repair mission that results in the destruction of the ship, and an intense sequence with the astronauts rendezvousing with an orbiting satellite and trying to rescue an overshot Tim Robbins. The sequence is utterly gripping for the twists that De Palma, Graham Yost and the Thomases keep throwing in – like Connie Nielsen’s seat-edge attempt to rescue Tim Robbins with a winch only for it to fall metres short.

Where Mission to Mars falls down is in its final act. The hard science build-up of the mission there and the sequence involving abandoning ship hold one enrapt. The deciphering of the code and entry into the mausoleum builds an appropriate sense of awe. However, the revelation of the aliens is banally underwhelming. The images of a viable Mars destroyed and the seeding of life on Earth is scientifically credible but the film trades in banal images of transcendent beings and universal brotherhood that have been worn to the point of cliche by the likes of 2001: A Space Odyssey, Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and The Abyss (1989). The alien, even if it meant to be a hologram, looks like a bad CGI cartoon and the heartstrings the sequence attempts to pull are simplistic in extremis. The final image of Gary Sinise going off to the stars aboard a rocketship farting a cute trail of blue smoke is an insipid let down for an otherwise three-quarters great film.

Brian De Palma’s other genre films are:– the absurdist comedy Get to Know Your Rabbit (1972), the psycho-thriller Sisters/Blood Sisters (1973), the rock musical Phantom of the Opera parody The Phantom of the Paradise (1974), the reincarnation thriller Obsession (1976), the psychic powers films Carrie (1976) and The Fury (1978), the psycho-thrillers Dressed to Kill (1980), Blow Out (1981), Body Double (1984), Raising Cain (1992) and Femme Fatale (2002). De Palma (2015) is a documentary about De Palma’s life and films.

(Winner for Most Underrated Film and Nominee for Best Original Screenplay, Best Special Effects and Best Production Design at this site’s Best of 2000 Awards).

Trailer here