aka Warriors of the Wind

(Kaze no Tani no Naushika)

Japan. 1984.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Hayao Miyazaki, Based on his Manga, Producer – Isao Takahata, Music – Joe Hiaishi, Art Direction – Mitsuyoshi Nakamura. Production Company – Tokuma Shoten/Hakuhudo.

Plot

It is a thousand years after the Earth has been devastated by nuclear holocaust. Nausicaa is the princess of the people of the peaceful Valley of the Wind. They live a tenuous life trying to drive back the giant Ohm creatures and the toxic plant life of the Sea of Decay that live beyond the valley, using flamethrowers to eliminate every spore that comes their way. Suddenly the valley is invaded by the warships of the powerful Tolmekian people who announce that they are going to attempt to eliminate the Sea of Decay by unleashing against it one of the Great Warriors that started the original holocaust. Nausicaa is taken prisoner but makes an escape. Fleeing, she plunges into the world beneath the Sea of Decay where she discovers that the plants are not destroying the air but instead sucking the toxins from it and purifying the world again. As the Tolmekians mount their insane plan to unleash the Great Warrior, she rushes to stop an onrushing horde of angered Ohms that are heading towards the valley and destroying everything in their path.

In the 1990s-2000s, Japan’s Hayao Miyazaki has emerged as probably the finest animator in the world. Hayao Miyazaki did not start directing films until he was in his 40s. He worked for a number of years as an animator on various anime tv series, including Lupin III (1971-2), Panda! Go Panda! (1972), Heidi (1974), A Dog of Flanders (1975) and Future Boy Conan (1978). Miyazaki’s first film as director was a theatrical spinoff of Lupin III, the appealingly nonsensical slapstick caper The Castle of Cagliostro (1980). Nausicaa in the Valley of the Wind was his second film. Miyazaki would go onto make the likes of Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986), My Neighbor Totoro (1988), Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989) and Porco Rosso (1992), before great acclaim outside of cult anime audiences with Princess Mononoke (1997), Spirited Away (2001), Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), Ponyo on a Cliff By the Sea (2008), The Wind Rises (2013) and The Boy and the Heron (2023). Also of interest is The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness (2013), a documentary about Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli.

Nausicaa in the Valley of the Wind is based on a manga also by Hayao Miyazaki, which was published in seven volumes between 1982 and 1994. Miyazaki condenses the complex story he tells in the manga – in fact, he only films the first two volumes of the printed story. Nausicaa in the Valley of the Wind was originally released to English-language speaking audiences in a badly edited American version Warriors of the Wind, which cut some twenty minutes out of the film’s nearly two hour running time. (There are frequent unconfirmed reports that this was because the heroine appears to fly around on her glider with her bare bottom showing beneath her skirt). Miyazaki disowned Warriors of the Wind, in fact told people that they were best to forget it, and reacted so negatively to the experience that he subsequently added contractual stipulations that none of his films be cut in any way. A restored subtitled print was re-released by Disney in 2004, along with a host of other Hayao Miyazaki titles.

Nausicaa in the Valley of the Wind is a post-holocaust film, although has little to do with any of the stock car derbies in the ruins of civilization that were being seen in contemporary live-action films around the same time following Mad Max 2 (1981) and its numerous copies. Instead, Hayao Miyazaki’s concerns are strongly environmentalist. (A strong interest in environmentalism runs throughout almost all of Miyazaki’s films – many of the themes here are later reflected in Princess Mononoke).

Nausicaa in the Valley of the Wind certainly echoes Mad Max 2 et al in that it is a reflection of the Cold War nuclear arms race that was being hyped anew by Ronald Reagan in the mid-1980s. Although, where Mad Max 2 and most of its ilk avoid any political subtext, Nausicaa in the Valley of the Wind comes out with a strong one. The Valley of the Wind appears to stand in for a pacifist, non-militarised Japan caught in a standoff between two warring superpowers that are wanting to unleash WMDs against the mutual menace. Indeed, Nausicaa in the Valley of the Wind could even be taken as far as to be read as a direct critique of the American military presence that occupies Japan to this day.

Nausicaa in the Valley of the Wind is a film of soaring humanism, with the heroine coming to represent a sole individual who stands up against the warring factions with forthright pacifism and an ardent belief in the environment. The film’s real beauty is in a conceptual reversal that comes part way through where we come to see that the marauding Sea of Decay is not a threat but a force of the environment trying to clean the Earth up from its despoliation by humanity. Like Princess Mononoke, Nausicaa climaxes on an extraordinarily beautiful moment of transcendent synthesis between forces of the environment and the human. (Hayao Miyazaki’s personal beliefs, one suspect, are Taoist ones that believe in a genteel, pacifist harmony between humanity and the environment).

Nausicaa in the Valley of the Wind was made in the mid-1980s before Hayao Miyazaki’s work attained the extraordinary contemplative beauty of background that has become his trademark. It was also before the advent of computer-assisted animation and Nausicaa comes in a much more limited and traditional form of anime, not unlike tv work. (This was a function of the fact that Miyazaki had not yet formed his Studio Ghibli production company and was operating with a limited budget). There is also a tinny 1980s-styled synthesizer score. Despite all of this, Miyazaki makes an extraordinarily beautiful and stirring film.

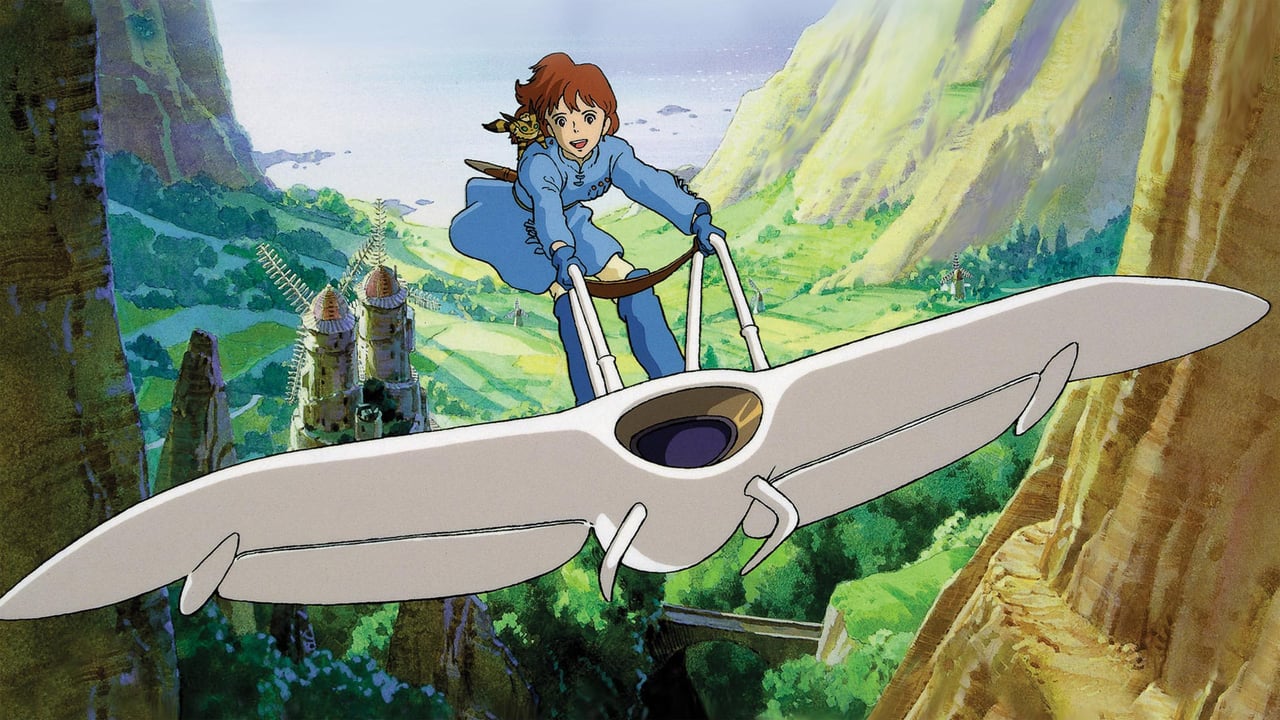

Hayao Miyazaki’s films often seem to reflect a love of flight – see also Porco Rosso, Laputa, Kiki’s Delivery Service, Howl’s Moving Castle and especially The Wind Rises, the biography of a Japanese airplane designer. Nausicaa is filled with flying machines – from the heroine zipping around on her jet-powered surfboard to the giant invading Tolmekian machines that seem modelled on B52 bombers, to a plane that appears to have been literally conceived as a gunship – a machine that is like the barrel of a revolver with wings. There is a great deal of exhilaration to the scenes of the planes shooting one another down, crashing and crews boarding ships in mid-air like marauding pirates.

Most of all though, the beauty of Nausicaa in the Valley of the Wind is its dizzying sense of scale – the tiny frail humans in the valley pitted against the vast forces of the oncoming Sea of Decay and in particular the stirring climactic scenes with the bucket ship flying before the giant tide of Ohms lowering a dead baby, the whole sea suddenly lit up by a flare and the image of Nausicaa facing the oncoming Ohms like a single person standing before a tidal wave. However, it is the final moments that leave everything else for dead as thousands of the gorgons invade the valley to be blasted apart by the vast lumbering Fire Monster, Nausicaa’s reckless flight down into the face of the horizon-spanning gorgon onslaught, her tiny body being battered out of the way by the hurtling mass and the transcendent beauty of the image of the Ohms lifting her body up between them to give life back to her from within their gestalt. Truly extraordinary filmmaking.

What also strikes one watching Nausicaa in the Valley of the Wind is the number of similarities between it and Frank Herbert’s Dune (1965), which was notedly also filmed by David Lynch as Dune (1984) in the same year that Nausicaa came out. Both Nausicaa and Dune have as hero(ine) a prince(ss) heir whose father is killed off when an invading army takes over their peaceful enclave by force; both also have a hero(ine) who discovers unique powers throughout that aid them in leading the resistance; both feature gigantic worm-like creatures; both feature people trying to life in an inhospitable world, where those who succeed in doing so are those who come to an understanding of and harmony with the environment; and both feature massively-scaled climaxes with the worm creatures riding in to save the day.

Trailer here