USA. 1959.

Crew

Director/Producer – Stanley Kramer, Screenplay – John Paxton, Based on the Novel by Nevil Shute, Photography (b&w) – Giuseppe Rotunno, Music – Ernest Gold, Special Effects – Lee Zavitz, Production Design – Rudolph Sternad. Production Company – Lomitas Productions.

Cast

Gregory Peck (Commander Dwight Towers), Ava Gardner (Moira Davidson), Fred Astaire (Julian Osborn), Anthony Perkins (Lieutenant Peter Holmes), Donna Anderson (Mary Holmes), John Tate (Admiral Birdie)

Plot

January, 1964. The Northern Hemisphere has been wiped out in a nuclear war. Australia waits for the winds that will bring the radiation fallout that will eventually kill them too. An American submarine has survived and docked in Melbourne. The crew make a return journey to the US to investigate random radio messages coming from San Diego and see if anyone is left alive. Back in Australia, people wait for the radiation to arrive with varying degrees of despair and denial.

On the Beach was once called ‘the most important film of our time’. Watching its slow melodrama today it is difficult to believe that people could have been seen it as that. However, things were very different in 1959. Director Stanley Kramer certainly regarded the film as being of monumental importance – it had simultaneous premieres in various cities around the world, including Melbourne (the first ever film to do so).

Looking back from four decades later, it is sometimes difficult trying to gauge just how the Cold War did affect people in the 1950s. Certainly, if the science-fiction of the period is anything to go by, people were utterly paranoid with fear of Communist infiltration and the shadow of imminent nuclear destruction. Up until On the Beach, cinematic Bomb anxiety had only been expressed in the metaphoric catharsis of atomically revived dinosaur and enlarged creatures in films such as The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), Them! (1954) and their ilk.

The only films up to that point to deal with nuclear realities head-on had been Five (1951), the cheap Day the World Ended (1955) and The World, the Flesh and the Devil (1959) and all had faltered in various ways in the clear spelling out of their message, ultimately opting for a cautious optimism, showing survivors heading off to make a better world out of the rubble of the old. On the other hand, On the Beach is notable in its bleakness and the certainty that nobody would survive. (For a more detailed overview see Films About Nuclear War).

What is discernible is the subsequent change wrought in the nuclear war genre after On the Beach came out. It was as though it had achieved a psychological breakthrough that suddenly gave filmmakers the freedom to discuss anxieties openly. Almost immediately after the giant atomic monster movie as a species began to die out and suddenly the floodgates were open to the likes of Dr Strangelove or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), Fail-Safe (1964) and The War Game (1965), all of which came determined to ram home the realities of nuclear war in the grimmest possible light. Of course in the real world, the Cuban Missile Crisis also occurred in 1962, the point that the whole world came the nearest it ever had to all-out nuclear war.

As with On the Beach, all of these were A-budget films, well out of the B-budget ghetto that the atomic monsters stomped about in. They were also made by well-known directors – Stanley Kramer, Stanley Kubrick, Sidney Lumet and Peter Watkins (fresh from the success of the BBC’s Culloden [1964]) – and used A-budget actors. All were also shot against prevailing trend in black-and-white, the film stock that has been most associated with the unblinking eye of reality.

On the Beach‘s distinction is not that it is a great film, merely that it was the first. Certainly, it reduces the nuclear holocaust to absurdly mannered melodrama. The intention to represent the human face of the holocaust is a fine one, but the melodramas present – Can Gregory Peck face the fact that his wife and children are probably dead and go on to love Ava Gardner? Can she raise herself from alcoholic indifference for the love of a good man? Can Anthony Perkins persuade his wife to take the suicide pills? Will Fred Astaire kill himself in his near-suicidal wish to race a Grand Prix? – reduce the film to soap-operatic banality.

Despite the fact that all life on Earth has been destroyed, we never see a single corpse throughout. The end of the world hardly dents the composure of its stars – Gregory Peck’s noble acceptance and both Ava Gardner and Donna Anderson’s subservient feminine compliance are held up as the ideals of behaviour in the face of adversity. (The film’s inherent sexism is never more clearly demonstrated than in the ending that concludes on a tragic parting between Gregory Peck and Ava Gardner simply it seems because women are not allowed on board a submarine – even at the end of the world).

The film is not exactly helped by an incredibly wooden performance from Gregory Peck – watching him trying to display emotion over the death of his wife and children is a ghastly sight to behold. With scenes like the one where two oldsters in a men’s club complain how there isn’t going to be time to get through the four hundred bottles of port, one can understand Stanley Kubrick’s inclination to turn the nuclear holocaust into a black comedy in Dr Strangelove.

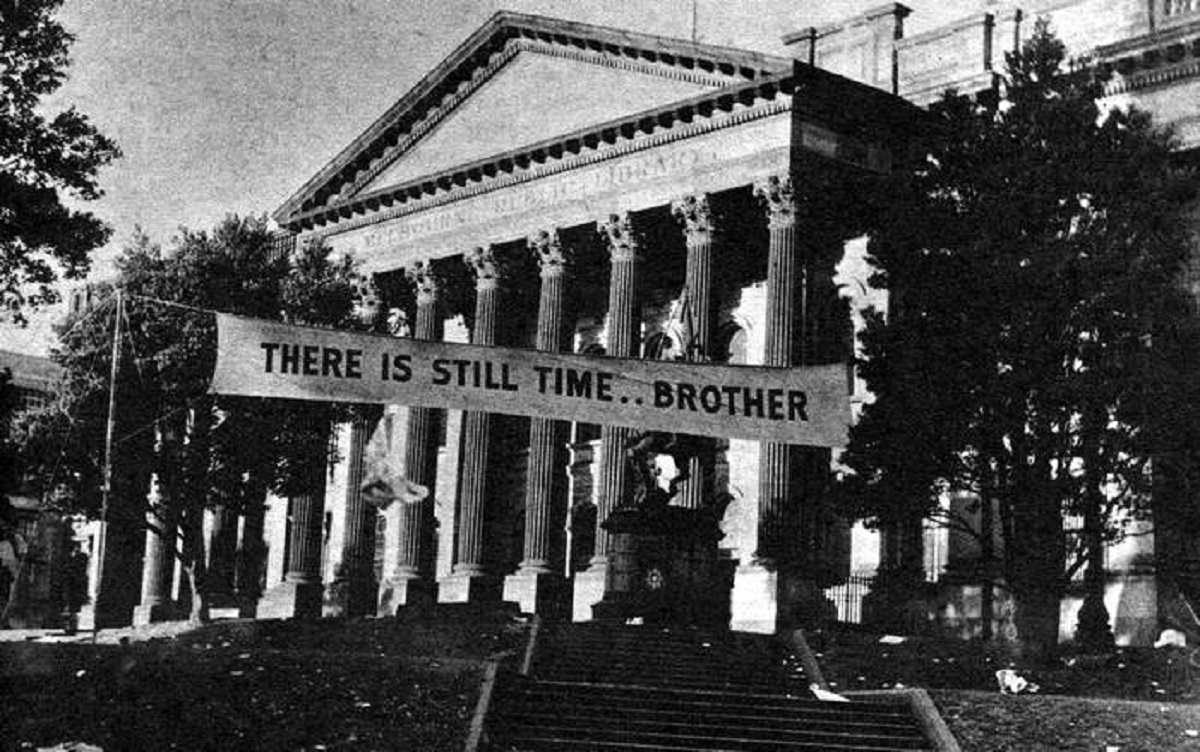

The pace also drags hideously. The reason for this is that Stanley Kramer deems it necessary to spell every issue out in bold several times over. He leaves nothing understated. The film literally talks us to the end of the world. And not merely content with portraying the end in a grim light, Kramer at the end turns and directly preaches to the audience, allowing with an appalling heavy-handedness the film to fade out on the image of a Salvation Army banner, “There is Still Time … Brother” sitting in the midst of a city empty of all human life.

Despite itself, On the Beach does still impress. The bleakness of some of its imagery – dead cities, people queuing up for suicide pills – does strike, even if most of this comes directly from Nevil Shute’s book. No image more potently demonstrates the death of an entire continent than the journey to the US in search of the source of the radio signals only to find they are being sent by a Coke bottle caught in a window shade being blown by the wind against a radio transmitter key. The scene with the crewman who has decided to swim into San Francisco sitting in a boat conversing with the submarine, aware of the fact that he is going to die, holds a degree of poignance – although the image of a man in a boat talking with pained melodrama to a periscope poking up out of the water holds its own level of surreal banality.

The Nevil Shute book was later remade as a tv mini-series On the Beach (2000) by Australian director Russell Mulcahy. This had the benefit of an authentic Australian cast with Rachel Ward in the Ava Gardner part and Bryan Brown in the Fred Astaire role, as well as Armand Assante as the American naval commander. This version seems to be a remake of this film more than it is an adaptation of the Nevil Shute book and covers all the basic aspects here. It is directed with a lush romantic sweep and has a number of worthwhile moments.

This was the fourth film for director Stanley Kramer (1913-2001), previously best known for the interracial escaped convicts film The Defiant Ones. Kramer subsequently went on to a career making big important, message-heavy films such as Inherit the Wind (1960), Judgment at Nuremberg (1961) and Ship of Fools (1965), as well as comedies like It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World (1962) and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967). Kramer never directed any other genre films, although did produce a couple of others with the psycho film The Sniper (1952) and the Dr Seuss film The 5000 Fingers of Dr T (1953).

Trailer here