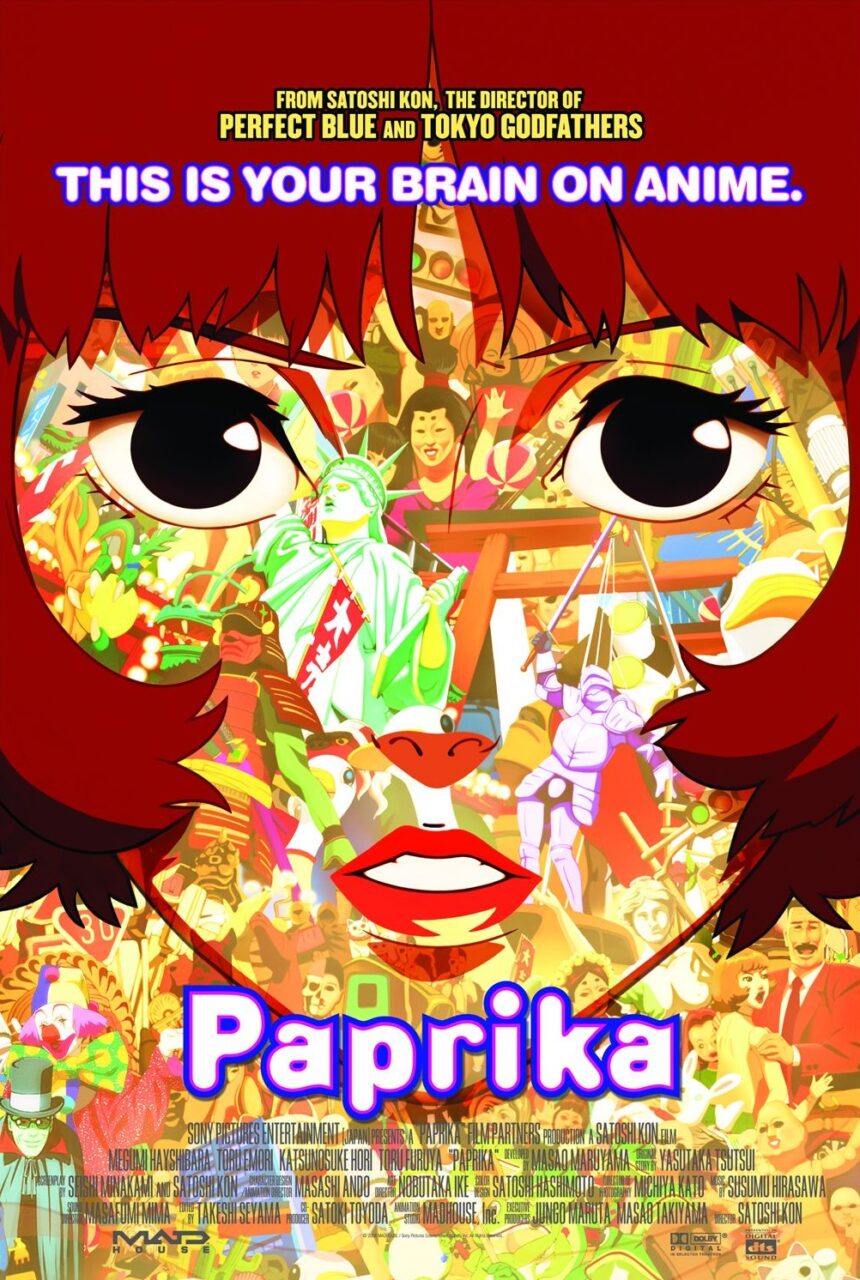

Japan. 2006.

Crew

Director – Satoshi Kon, Screenplay – Satoshi Kon & Seishi Minakami, Based on the Novel by Yasutaka Tsutsui, Photography – Michiya Katou, Music – Susumu Hirasawa, Animation Supervisor – Masashi Ando, Art Direction – Nobutaka Ike. Production Company – Madhouse.

Plot

Chiba Atsuko is part of a research project that has developed a device known as DC Mini that allows a therapist to enter and interact with a person’s dreams. Though the device has not yet been perfected, Chiba has been working as a therapist for the police detective Kogawa using a virtual alter ego known as Paprika. Chiba’s co-developer Tokita then informs her that the prototype of the DC Mini has been stolen. This means that the thief can enter into the dreams of any person who has used the DC Mini. Chiba’s colleague, the aging Dr Shima, goes crazy as his dreams become colonized by the hallucinations of another patient. Chiba retrieves Dr Shima from the hallucination using Paprika. It is believed that the thief was Tokita’s assistant Kei Himuro but Chiba finds that this is not the case. As the dreams begin to spread and take over people everywhere, Chiba races to find the real thief.

Paprika comes from Japanese animator Satoshi Kon. Satoshi Kon first appeared writing the scripts for Katsuhiro Otomo films like World Apartment Horror (1991) and Memories (1995) and then went onto direct with the anime psycho-thriller Perfect Blue (1997), which found an appreciative international audience. Subsequently, Kon made the surreal fictional biography Millennium Actress (2001) and the comedy Tokyo Godfathers (2003). These gained Kon an increasing degree of acclaim internationally before his premature death in 2010 at age 46.

Almost universally, Paprika received notices that celebrated it as being clever, visually rich, with such a profusion of ideas that it was impossible to take everything in in one viewing and so on. On the other hand, I had a different reaction to most others. Maybe it is just that I have seen more genre movies than most of the other mainstream critics out there.

In truth, the ideas that Paprika has are old hat. The dream exploration device and dream therapist/dream incursion idea have been done before in films like The Electronic Monster (1960), Dreamscape (1984), A Nightmare on Elm Street III: The Dream Warriors (1987), The Cell (2000), Nightmare Detective (2006). With the success of the subsequent Inception (2010), there was an upsurge in dreamscape films with the likes of Vanishing Waves (2012), Mindscape (2013), Real (2013), Incarnate (2016) and Lucid Dream (2017).

Paprika does nothing with the idea that could be considered particularly novel. It does have a slightly different take to most of these – that of the heroine combating a villain who is trying to colonize other people’s dreams, although this made me think no further than a variation on Freddy Krueger in A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) and sequels, albeit told in the language of science-fiction and anime rather than horror.

Paprika is certainly Satoshi Kon’s most beautifully animated film. Some of the surreal dream images come with a sinister dis-ease. Particularly striking is the image of a carnival of toys and figures from Japanese children’s stories, not to mention ambulatory refrigerators, giant frogs, rains of blue butterflies and the adorable image of the nerdy Tokita turned into a toy robot with rotating head that dance through the streets – something that with each appearance becomes increasingly more cacophonous and sinister.

On the other hand, Satoshi Kon’s images buy into surprisingly traditional anime cliches such as the mass destruction climax. There is a striking scene where the secondary villain shoves his hand inside Paprika’s body and forces it all the way up, tearing her skin off and revealing her real identity as Chiba and then seeing him taken over by the main villain whose head forces its way out of his shoulder – but this is undone by seeing the villain then turn into a standard mass of tentacles trying to rape the heroine, which has become a cliche of hentai anime. The villain’s motivation is one-dimensional anti-Luddhite hysteria where the why behind their scheme is never particularly clear.

A number of recurrent themes run through Satoshi Kon’s films. As in Perfect Blue, he has an emotionally repressed heroine who leads an unhappy everyday life, which is contrasted with the double life that she lives through an idealised wish fulfilment alter ego. As with the heroine in Millennium Actress, there is the character of the detective Kogawa who seems to live in an allegorical dream world represented by various genres of movies where Satoshi Kon conducts pastiches of James Bond, thriller and Tarzan movies and with the heroine at one point flying through the clouds like Sailor Moon or one of the various preadolescent heroines of shoujo anime. (In an amusing joke, when the detective goes to the movies at the end after conquering his dislike of cinema, one of the films that is showing on the billboard is Satoshi Kon’s own Tokyo Godfathers).

The theme that continually runs through Satoshi Kon’s films is of the blurred line between the real and the imagined – you might well get the impression from some of Kon’s films (especially Millennium Actress) that he regards the imagined (in particular the cinematic) as more real than the real world. Unlike filmmakers such as Joe Dante and Kevin Williamson who seem to make a regular feature of manically quoting genre cinema and inviting their audiences to celebrate the enjoyment of the same films they have seen, Satoshi Kon seems to be searching for something deeper beneath recycled cinematic imagery. What Kon seems to be saying is that the characters in the dreamed life that is popular culture function as our alter egos – the heroine is emotionally repressed but puts all her life into the carefree adolescent superheroine, while cinema comes to stand in for the detective’s repressed feelings.

Satoshi Kon is not dissimilar to his countryman Kiyoshi Kurosawa, the director of horror films like Cure (1997) and Pulse (2001), who always creates plots that leave a host of unanswered questions. The plots of both Perfect Blue and Millennium Actress disappear into frequent total confusion about what is going on. Paprika is certainly less confusing than either of these and for the most part a relatively straightforward and enjoyable storyline. Nevertheless, it does contain a number of what might be considered excessive confusions. I was never sure why the heroine maintained her alter ego as Paprika that nobody else, not even most of the people she works with, knows about. If the machine is only in its test stage, what is the virtual barroom where Kogama goes to for his dream therapy and where Chiba hangs out as Paprika doing on the internet? The processes whereby the DC Mini went from controlling those who had used the machine to be able to infect the population en masse were not clear. The climax of the film also has the same fault as many of the sequels and copies of A Nightmare on Elm Street did in that the dividing line between the dream and reality becomes so eroded that you are never clear what is going on.

Trailer here