USA. 1959.

Crew

Director/Screenplay/Producer – Edward D. Wood Jr, Photography (b&w) – William Thompson, Music – Gordon Zahler, Special Effects – Tommy Kemp, Makeup – Harry Thomas. Production Company – J. Edward Reynolds Productions.

Cast

Gregory Walcott (Jeff Trent), Mona McKinnon (Paula Trent), Duke Moore (Inspector Harper), Tom Keene (Colonel Edwards), Dudley Manlove (Eros), Joanna Lee (Tanna), Tor Johnson (Inspector Clay), Vampira (Ghoul Woman), Bela Lugosi (Ghoul Man), Lyle Talbot (General Roberts), John Breckinridge (The Ruler), Criswell (Narrator)

Plot

Aliens are intent upon destroying Earth because humanity’s warlike tendencies are starting to endanger the rest of the universe. Having been foiled in their preceding attempts, the aliens launch Plan 9 – to take over the world by raising the dead from their graves. Landing in a Hollywood graveyard, they resurrect three dead people – a murdered police inspector and a widower and his wife.

Plan 9 from Outer Space, the film acclaimed as the worst ever made, is a name that has become not only a genre joke but one that seems to represent every bad Z-budget science-fiction movie ever made. Plan 9 from Outer Space‘s legendary ineptitudes, the behind-the-scenes story and the lives of the people who made it have become the stuff of cult fascination. Conversely, rather than a black star rating, this site gives Plan 9 from Outer Space a four star (very good) rating. The cult of bad films is something that perversely beggars questioning of exactly what bad means. How is it possible to call a film bad when that badness is something that is being enjoyed by its audience?

Maybe it is that ‘bad’ is a term that has become so loosely applied that our critical terminology is not versatile enough to allow our stupid, stupid minds to stretch to the various shadings of bad. New labels are needed. There should be a term to mean ‘the bad that comes from exaggerated expectations’ where a film falls disastrously short of the hype and expectation that is lavished upon it – such examples might include Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace (1999) or King Kong (1976). There is also ‘bad ineptitude’, which would cover films that come with gaping technical gaffes such as Plan 9 from Outer Space. There might be ‘artistic ineptitude’ that would cover films of exaggerated pretensions like Zardoz (1974) or Born of Fire (1986). There would be ‘ill-conceived bad’, which would cover films that should never have been made in the first place – a great host of sequels and remakes could be placed here. Then there is ‘morally repugnant bad’ for films that leave an unpleasant aftertaste (many horror films are often categorised thus) or have an offensively reactionary jingoism, such as John Wayne’s The Green Berets (1968) or Falling Down (1993).

Finally, there is the ‘deliberately bad’ where one can place a body of films that sprang up in the 1980s, making a virtue of their cheesiness and attempting to create a faux bad movie atmosphere – almost the entire outputs of some directors such as Fred Olen Ray, David DeCoteau, Jim Wynorski consist of such deliberately bad films.

Even when talking about the ineptly made there is a world of difference between films like King Kong Lives (1986), Batman & Robin (1997) and The Haunting (1999), which were made with enough money and people present that someone in the creative process should have known better, and films like Plan 9 from Outer Space and Robot Monster (1953), which were made by people who seemed to be putting all they could in with zero resources and carrying on regardless, sometimes despite their cast, crew’s and own glaringly evident lack of talent.

Plan 9 from Outer Space and the oeuvre of Edward D. Wood Jr inhabits the place reserved for the slow kid in the class where one tries to find ways of lavishing out encouragement so as not to discourage the clear effort to create something that has gone into the enterprise. There was always something endearingly personal about Edward D. Wood Jr’s films. He would shoot in one take and seemed to care more about the vision he had in his head than whether he or his crew were ever adequately conveying it.

Wood’s films seem filled with impassioned speeches where you felt that Wood clearly had something to say, even if the purple prose and hyperbole of his writing failed him. Plan 9 from Outer Space has the classic piece of overwrought simile [regarding Bela Lugosi mourning his wife]: “The home they had so long shared together became a tomb; the sky to which she had once looked was now only a covering for her dead body. The ever-beautiful flowers she had planted with her own hands became nothing more than the lost roses of her cheeks.”

In terms of plot, Plan 9 from Outer Space is an incoherent hodgepodge that seems to shift among various different characters and all over the place without a clear focus. It might have been interesting to see what would have happened if Edward D. Wood Jr had ever been granted a halfway decent budget, rather than no budget and a script that seemed less like it were composed around whatever Wood could manage to sling together on the resources he had. Wood’s Bride of the Monster (1955), for example, rather than a bad movie, is actually a reasonably engaging mad scientist effort.

Plan 9 from Outer Space‘s failings are legendary. Scenes flick back and forward between day and night because Wood had shot day-for-night but then forgot to have them processed at the lab. There are the classically bad sets – the plane cockpit that consists only of a curtain and two people on chairs who rock around while the plane itself never moves; or the graveyard scenes where Tor Johnson stumbles and knocks a cardboard tombstone over. There are the classic pieces of bad dialogue:– “One thing’s sure. Inspector Clay’s dead. Murdered. And someone’s responsible.” A UFO is described as cigar-shaped, yet when it appears is saucer-shaped. Or Paul Marco’s cop who keeps scratching his head with his revolver throughout the film. Criswell’s portentous, urgent narration over the credits – “Can you prove it didn’t happen?” and “future events such as these will affect us in the future” – has audiences in hysterics even before the film starts.

The behind-the-scenes story of Plan 9 from Outer Space has almost grown into a greater fascination than the film itself. A few years earlier, Wood had fallen into the company of Bela Lugosi. Lugosi had once been at the height of his career with Dracula (1931) but his career throughout the 1940s had charted a single line downwards until he became the chief attraction in the cheapest of poverty row studio mad scientist films. By the 1950s, Lugosi was washed up and had developed a drug and alcohol dependency so bad that by this point that he was reputedly drinking formaldehyde because it was the only thing that would have an effect on him.

Wood placed Bela Lugosi in two of his films – Glen or Glenda? (1952) and Bride of the Monster. Wood had originally intended Plan 9 from Outer Space as a career comeback for Lugosi and had written a script for him to star in entitled Tomb of the Vampire. He shot about two minutes worth of scenes in and around Lugosi’s home in 1956, but then Lugosi curtailed Wood’s plans for reviving his career by dying a few days later.

Holding onto the few minutes of footage, Wood obtained funding from, of all places, a group of Baptist ministers (who thought the profits from the film would allow them to finance a series of Biblical films) and combined the Lugosi material into a new script Plan 9 from Outer Space. (It was originally entitled Grave Robbers from Outer Space but this was nixed by the Baptists). In the new script, Lugosi is turned from a vampire to a zombified widower. Wood had the ingenious idea of recasting the part with a double in Tom Mason, his wife’s chiropractor. Although Wood instructed Tom Mason to cover his face with his cape, Mason is clearly a foot taller than Lugosi and with noticeably lighter hair.

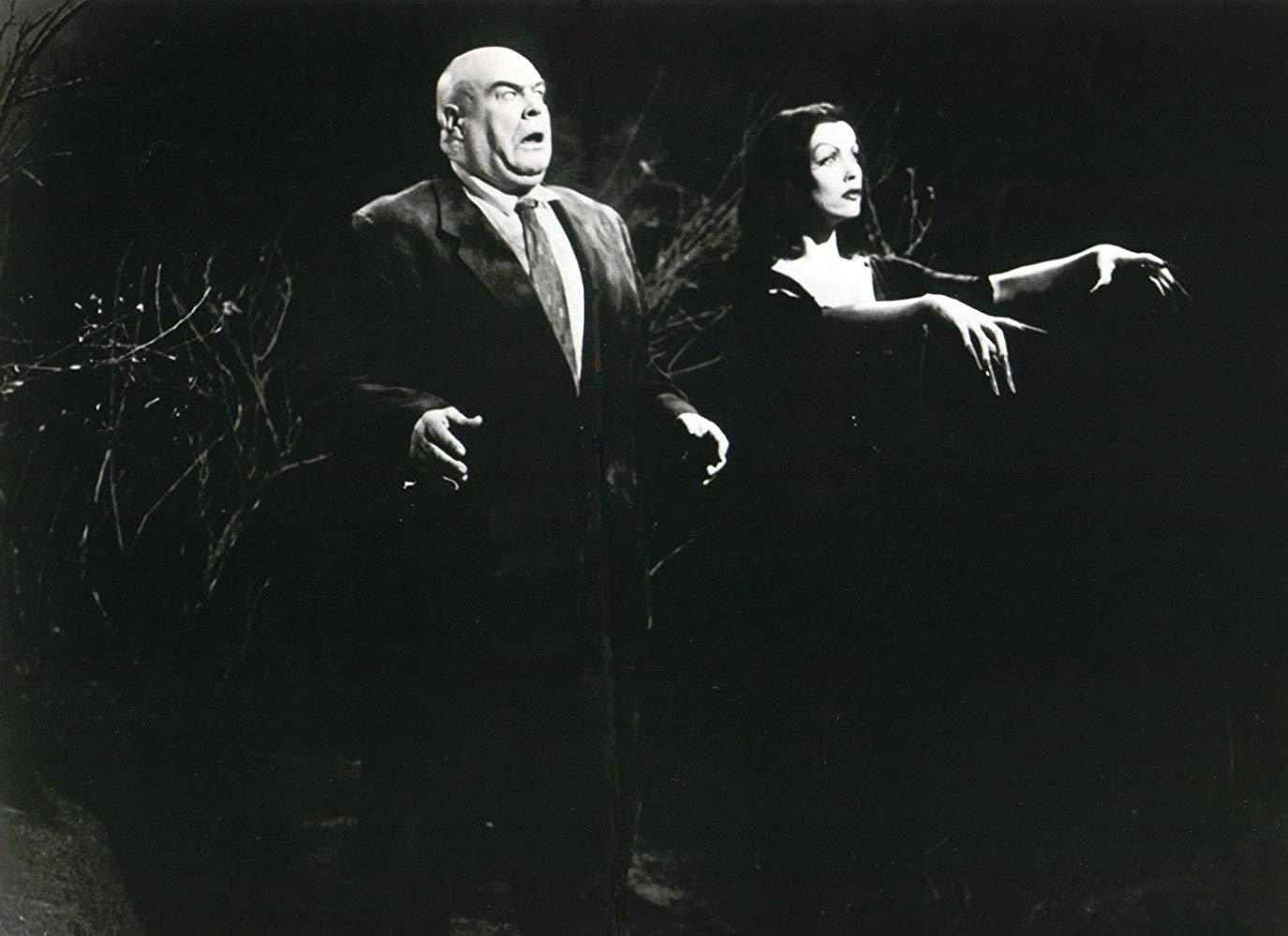

As was always the case with Edward D. Wood Jr’s films, Wood culled his cast from the various Hollywood hangers-on and oddballs he gathered around him. Plan 9 from Outer Space manages to gather the most fascinating of Edward D. Wood Jr casts – at times, the film resembles a John Waters freakshow. Outside of the tragic Bela Lugosi, Wood managed to get Vampira (alias Finnish-born Maila Nurmi), the original tv horror hostess (she sued Elvira in the 1980s for ripping her act off), who creates a striking presence in the film with her seventeen-inch waistline and nearly six-inch fingernails. Equally striking in terms of presence is the 400-pound Swedish wrestler Tor Johnson, a minor Z movie actor of the era, who appears as a ghoulishly bloated zombie.

The film is narrated by the fascinating Criswell. Born Jerome Criswell, he gained fame as a prophet through a series of syndicated newspaper columns and later tv talkshow appearances where he predicted the emergence of NAFTA, that something would happen to John F. Kennedy in November 1963 and that Ronald Reagan would become the Governor of California, although was slightly out in his predictions that humanity would encounter aliens in the 1980s, that Mae West would become the President of the US and that the world would end in August 1999. At the centre of this fascination was the bizarrely entertaining figure of the cross-dressing Wood himself, who claimed to have worn bra and panties under his uniform while in the Marines in WWII and would direct his films while dressed in women’s angora sweaters and a pink chiffon dress.

The fascination with Plan 9 from Outer Space, Edward D. Wood Jr and his life has become a major cult. This began with Harry and Michael Medved’s The Golden Turkey Awards (1980), which ridiculed Plan 9 from Outer Space as the worst film ever made and gave Wood the title of worst director ever. Contrarily, this served to create a major new fascination with Wood and his films. Lost Edward D. Wood Jr films were revived and some saw the light of a projector for the very first time. There have been three Ed Wood biographies – Rudolf H. Grey’s Nightmare of Ecstasy: The Life and Art of Edward D. Wood Jr (1992), Lee Harris’s King of the B’s: The Biography of Edward D. Wood Jr (1995) and David C. Hayes’s Muddled Mind: The Complete Works of Edward D. Wood Jr (2001), and three documentaries Flying Saucers Over Hollywood: The Plan 9 Companion (1992), Ed Wood: Look Back in Angora (1994) and The Haunted World of Edward D. Wood Jr (1995), while Unspeakable Horrors: The Plan 9 Conspiracy (2016) is a mockumentary. Magazines like Filmfax seem to fill every second issue with an interview with someone who knew Wood. An episode of the alternate world-hopping tv series Sliders (1995-2000) amusingly featured a world where Wood was the President of the United States. This culminated in the making of Tim Burton’s affectionate biopic Ed Wood (1994). Outside of this, there grew a genre of deliberately bad movies, not to mention the popularity of Mystery Science Theater 3000 (1988-99, 2017-8) and its contemptible habit of screening old bad movies with dubbed-over laugh tracks.

Plan 9 (2015) was a loose remake that billed itself as the film Edward D. Wood Jr would have wanted to make. There was a purported sequel Plan 10 from Outer Space (1995) about alien invaders and Mormons, while several touted remakes have been announced. There was even a pornographic version Plan 69 from Outer Space (1993). A stage version of the film Plan Live from Outer Space was produced in Canada in 2006 and won several awards.

Edward D. Wood Jr’s other genre films are:– the transvestitism pseudo-documentary Glen or Glenda? (1952), the mad scientist film Bride of the Monster (1955), the script for the ape-human love saga The Bride and the Beast (1958), the fake medium film Night of the Ghouls (1960, released 1983), the script for the nudie horror Orgy of the Dead (1965); and the pornographic film Necromania: A Tale of Weird Love (1971).

Trailer here

Full film available online here:-