France/UK/Luxembourg. 2006.

Crew

Director – Christian Volckman, Screenplay – Alexandre de la Patelliere, Mathieu Delaporte, Jean-Bernard Puoy & Patrick Raynal, Story – Alexandre de la Patelliere & Mathieu Delaporte, Producers – Roch Lener, Aton Soumache & Alexis Vonarb, Music – Nicholas Dodd, Animation – Attitude Studio, Special Effects Supervisor – Pierre Villette, Art Direction – Pascal Valdes, Visual Concept – Marc Miance. Production Company – Onyx Films/Millimages/Luxanimation/Timefirm Ltd/France 2 Cinema.

Voices

(English Language Version)

Daniel Craig (Captain Karas), Catherine McCormack (Bislane Tasuiev), Romola Garai (Ilona Tasuiev), Ian Holm (Dr Jonas Muller), Jonathan Pryce (Paul Dellenbach), Kevork Malikyan (Nusrat Farfella), Rick Warden (Lieutenant Amiel), Breffini McKenna (Dmitri)

Plot

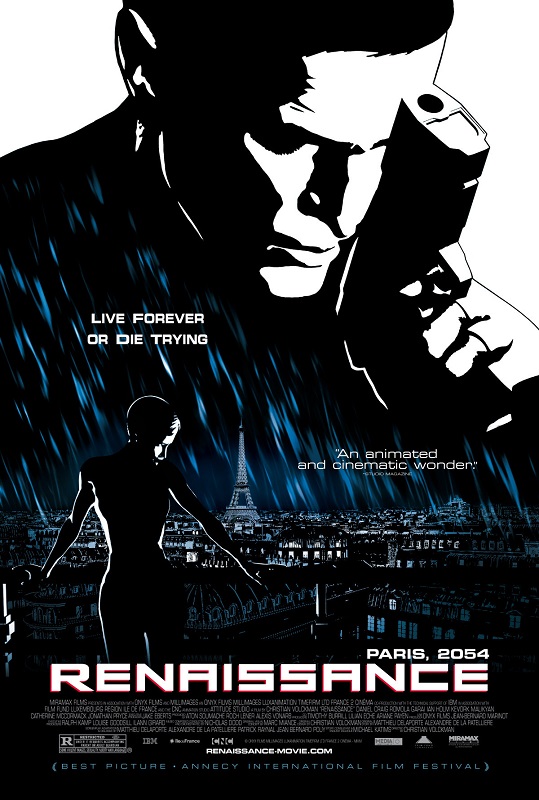

Paris, the year 2054. Police detective Karas is assigned to investigate after Ilona Tasuiev is reported missing, thought to have been abducted outside a nightclub. Karas begins investigating Ilona’s employer Avalon, which dominates the market in beauty and youth products, as well as her mentor, the genetic researcher Dr Jonas Muller. Karas forms a touchy relationship with Ilona’s sister Bislane and is later drawn into a relationship with her. As he investigates further, Karas discovers how Muller was engaged in research into progeria and longevity and how he deliberately killed a batch of experimental subjects. He realises that Ilona may have uncovered the secret to immortality – a secret that is being desperately sought by Avalon.

Renaissance is a fascinating animated film from France (principally). It has been made in the performance capture/animation process that was developed notably in Robert Zemeckis’s The Polar Express (2004) wherein sensors are placed on actors’ bodies and data recording their movements is fed directly into a computer and then rendered as animation. Renaissance is the debut feature from French director Christian Volckman who spent six years producing the film in a Luxembourg animation studio on a tiny $15 million budget.

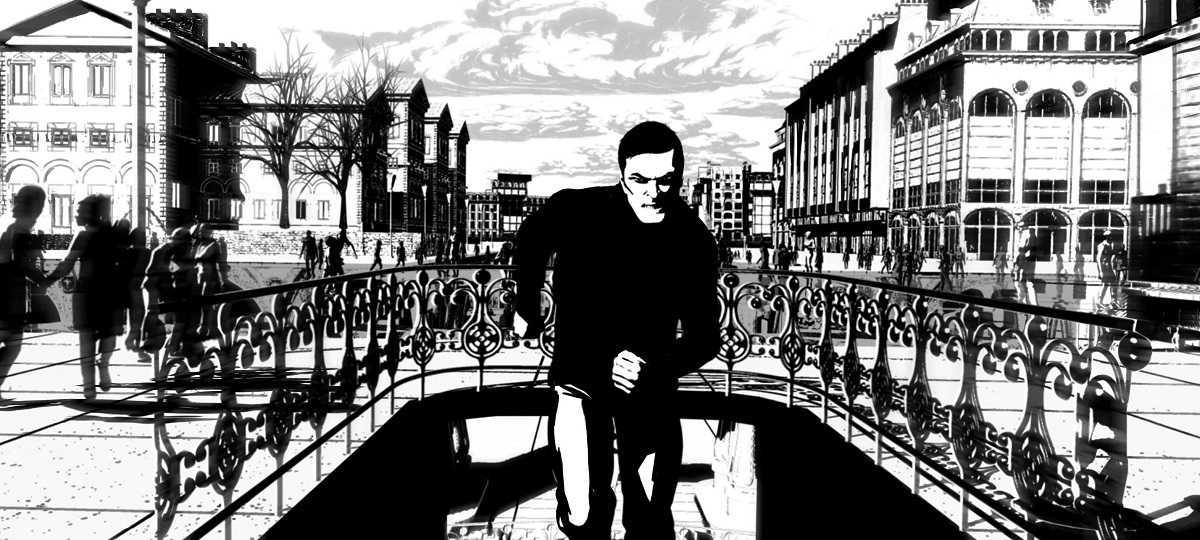

The entire film has been animated in black and white, where everything has been rendered into a stark two-tone contrast that leaves no grey shades in the middle. The results are visually exquisite – the contrast of light and shadow across the characters’ faces plays out like something out of an amazingly arty graphic novel. Volckman and his animators do dazzlingly showoffy things – contrasts between foregrounded reflections or in layered textures, even briefly bursting into colour during two shots where we see Claus Muller doing his doodles. One of the first shots in the film comes as we watch the animation camera move from an amazing aerial vision of the rooftops of Paris right down through the various street levels into closeup on the hero of the show. The three-dimensional depth of such a shot, and especially seeing it in the film’s highly stylised contrasts of white and black, is stunning.

There is a dazzling architectural beauty to the film – more so one suspects if you are a Parisian citizen where existing artifices have been subtly ‘futurised’ – in one scene, a business executive sits at his desk that has a glass floor beneath before at the end of the scene the camera pulls back to reveal he and his glass office are located in the midst of a strut that bisects a giant arc-shaped building; or a foot chase through the streets beneath Notre Dame cathedral where we see that the area has been built with a split level separated by glass floors with each of the pursuers on separate tiers. There are some dazzling action sequences – especially a breathtaking car chase through the streets of Paris and another sequence where Karas faces off a group of invisibility-cloaked gunmen in a shootout in a glassed-in rooftop conservatory.

Such a moody downbeat black-and-white future consciously evokes the look of film noir. Almost any film that attempts to do this cannot help but source Blade Runner (1982), which set the cornerstone when it comes to mixing dark moody futures and quoting film noir. The plot of Renaissance also resembles Blade Runner in a number of ways – the grim detective hero investigating a trail of corporate deviousness; the eventual unveiling of a plot about people searching for a means to extend their lives.

Visually, Renaissance resembles Sin City (2005), which was likewise a film noir story that blurred almost all of the colour out of the frame and shot the film in highly stylised contrasts of black-and-white. Although the film that Renaissance resembles the most is actually the A Detective Story segment of The Animatrix (2003), which did the stylised futuristic film noir look in animated black-and-white several years before Renaissance came along.

Unlike Blade Runner, Renaissance offers up only a minimalist future. Christian Volckman has co-opted some of the Blade Runner/Cyberpunk look in terms of vast building-sized holographic ads and some occasional bits of nifty gadgetry, most notably the Avalon hitmen and their invisibility camouflage gear. On the other hand, compare Renaissance to the other most recent major science-fiction (and animated) work to emerge from France – Enki Bilal’s Immortal (ad vitam) (2004), where Bilal took the opportunity afforded by animation to create a genuinely alien vision of the future. By contrast, Renaissance stays mostly with the familiar present, doing not that much beyond the occasional pieces of architecture to make the vehicles and costumes seem futuristic.

The plot follows standard film noir patterns (and eventually clichés). The characters never fully engage with us they way you feel they should – they often seem like cut-outs of characters such as the burned-out detective, the greedy businessman, the morally ambiguous woman the hero liaises with, the underworld kingpin who becomes the surprise seventh cavalry. By its nature, film noir has an extraordinary ability to draw us into inner moods, but Renaissance‘s failing may be that it seems more interested in the animation, architecture and action set-pieces but never fully engages us on a deeper level beyond its surfaces.

Though the plot follows a generic film noir blueprint, in the last quarter its elements do coalesce into something science-fictional. Here though the film fails to fully engage on a conceptual science-fictional level as what we get is an old hat variant on the quest for immortality, which arrives at a tired conclusion that this is only a discovery that humanity would abuse and we are better off without such knowledge. Visually however, Christian Volckman has done a superlative job with Renaissance and deserves full marks.

Christian Volkman did not make another film for thirteen years before returning with the live-action horror film The Room (2019) about a couple that a buy a house that has a room that makes wishes come true.

Trailer here