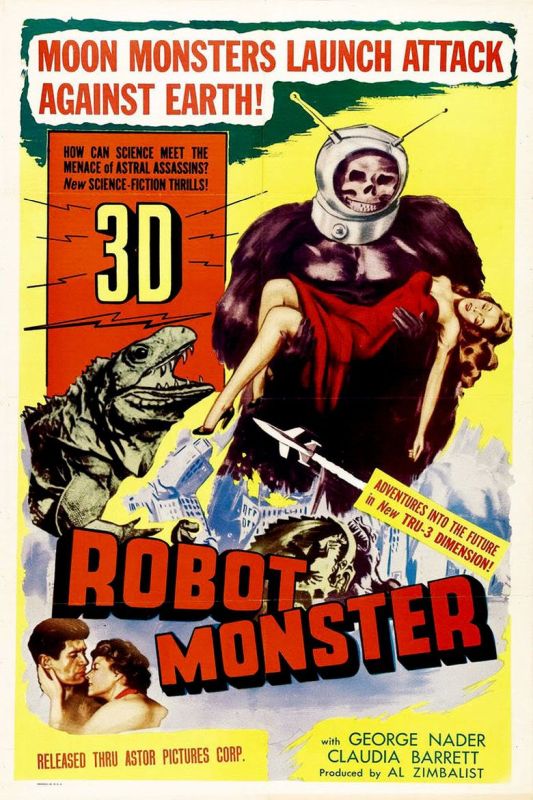

USA. 1953.

Crew

Director/Producer – Phil Tucker, Screenplay – Wyott Ordung, Photography (3-D, b&w) – Jack Greenhalgh, Music – Elmer Bernstein, Special Effects – David Commons & Jack Rabin, Gorilla Suit – George Barrows. Production Company – Three Dimensional Pictures.

Cast

George Nader (Roy), Claudia Barrett (Alice), John Mylong (The Professor), Selena Royle (Mother), Gregory Moffett (Johnny), Pamela Paulson (Carla), George Barrows (Ro-Man)

Plot

Earth has been invaded by the ape-like Ro-Men. The entire human race has been wiped out by the deadly Ro-Man calcinator ray, all except for a scientist who has managed to give his family an antidote. However, as the Ro-Man attempts to finish them off, it discovers desire for the professor’s daughter Alice and begins to doubt its mission.

Robot Monster is one of the classic so-bad-its-funny turkeys from the 1950s. It is right up there in terms of ineptitude along with Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959) and has as much in terms of hilarious gaffes, bad acting, bad special effects and bad dialogue as Plan 9 does. It has not gained the same cult appeal, probably because its behind-the-scenes story and the lives of its creative personnel lack the same freakish fascination. Like Plan 9, Robot Monster is a film that is hard to hate – it gets a four star rating here because the cheesiness of its ineptitude provides such an enormous degree of sheer entertainment value.

Robot Monster‘s ineptitudes are legion. The invading alien monster is one of the most hilarious in cinematic history – the part had originally been intended to be filled by a standard tin man robot of science-fiction cliche but director Phil Tucker found it too expensive to build a robot suit so instead cast George Barrows who had a gorilla suit and then simply placed a diving helmet that had antenna glued on over his head. There are endless scenes of Ro-Man stomping up and down the hillside. The only expression it seems to have is to shake its fist – the little boy escapes, does it pursue? No, instead it prefers to stay and shake its fist.

The Ro-Man attack on Earth consists of stock footage of B-52 bombers and of dinosaurs taken from One Million B.C. (1940), the one film in the science-fiction genre that must hold the record for being the most reused in other films, the same scenes of which are repeated several times over. At one point, you can clearly see the hand holding up the model rocketship as it spins about firing magnesium flare exhaust. The deadly Calcinator ray is a bubble-blowing machine – the film comes with the credit line “Automatic Billion Bubble Machine Provided by N.A. Fisher Chemical Products Inc,” which for some reason had audiences I saw the film with in hysterics.

The acting is atrocious – the children are clearly non-actors and bored with the exercise, while hero George Nader seems to spend the entire film running about with his shirt either off or artfully torn. The writing is frequently hysterical – the effects of the Calcinator Ray are represented by stock footage of B-52 bombers, yet somehow the Professor has managed to produce an antidote against this. (A viral antidote to the effects of bombs would be a truly unique invention). There is Ro-Man’s classic line of dialogue: “To be like the humans. To laugh, feel, want. Why are these things not in the plan? I cannot, yet I must. At what point on the graph do cannot and must meet?”

Robot Monster was made in 3-D to capitalise on the original 3-D fad that had been created by Bwana Devil (1952). These days most bad movie festivals only screen Robot Monster flat, although one US video version does release it on video in 3-D. The twist ending, revealing the story to have all been a young boy’s dream, which then starts all over again, is strikingly reminiscent of Invaders from Mars (1953), which was released only a matter of weeks before Robot Monster (and also originally shot in 3-D).

Director/producer Phil Tucker had previously produced a series of nudie pictures and reputedly written for pulp science-fiction magazines (although nobody has managed to find any examples of these, meaning either that they were very obscure magazines, that Tucker was publishing under a pseudonym or most likely that these claims should be regarded liberally). Tucker made the entire film in only in four days on a reputed $16,000 budget. It was filmed entirely in Bronson Canyon, the location for numerous Westerns, serials and a number of Star Trek (1966-9) episodes – there are, for example, no interior sets in the film.

There is the oft-repeated rumour that the film’s critical reception caused Tucker to attempt suicide with an overdose of sleeping pills – although this is not quite true. Tucker’s suicide attempt was due to the distributors of the film cheating him out of the profits, ending with distribution chains refusing to let Tucker even come in during general admission to see his own film and him being generally blacklisted in the industry, reputedly not even being able to get a job as an usher (again a claim one should treat liberally).

Nor is it quite the case that the film was universally trashed – The Medved Brothers, when they include Robot Monster in The Fifty Worst of Movies of All-Time (1977), selectively quote from a Variety review but in fact the full review is a generally positive one. Whatever the case, Phil Tucker soon recovered from his blacklisting and went on to direct several other films, mostly nudies. His one other genre offering was the marginally better budgeted alien invader film The Cape Canaveral Monsters (1960). He died in 1985.

Screenwriter Wyott Ordung later wrote other cheap science-fiction films such as Target Earth (1954) and First Man Into Space (1959) and directed Monster from the Ocean Floor (1954). There is the frequently repeated claim that Ordung wrote the script for Robot Monster in 30 minutes, although this is hard to believe – considering that the average script consists of 90 pages and allowing no time for such things as changing typewriter paper, making any mistakes on a page or pausing to gather one’s thoughts, this requires Ordung to have written one page every 20 seconds.

The only name on the credits that ever went onto anything of note was that of composer Elmer Bernstein who would compose the soundtracks for The Ten Commandments (1956), The Magnificent Seven (1960), To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), True Grit (1969) and Ghostbusters (1984).

The Ro-Man later made a cameo appearance in Joe Dante’s Looney Tunes: Back in Action (2003).

Trailer here