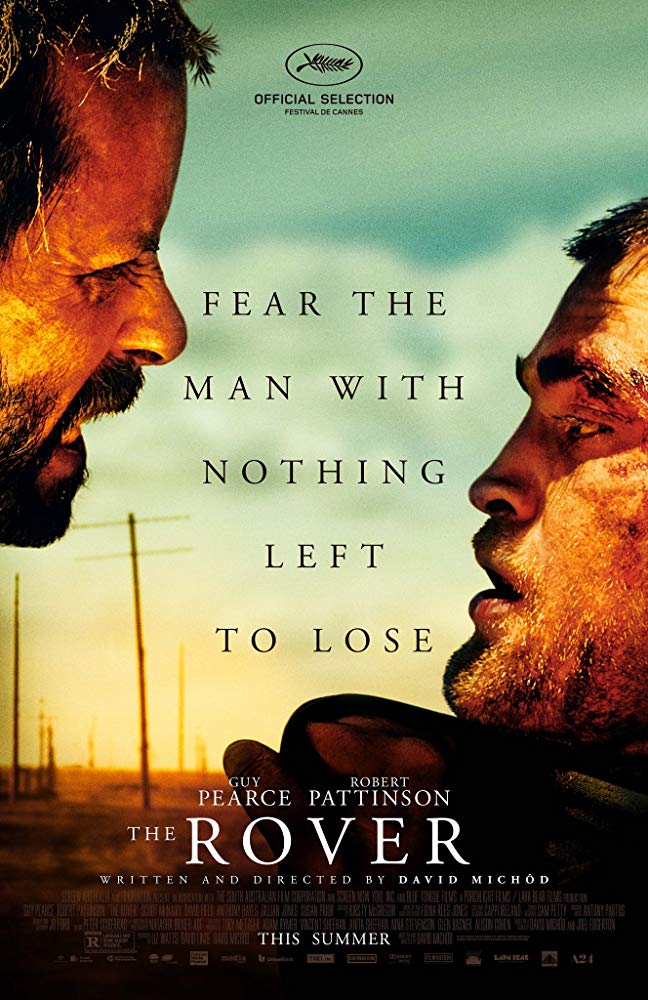

Australia. 2014.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – David Michôd, Story – Joel Edgerton & David Michôd, Producers – David Linde, David Michôd & Liz Watts, Photography – Natasha Braier, Music – Antony Partos, Visual Effects Supervisor – Dave Morley, Visual Effects – Fuel VFX, Special Effects Supervisor – Angelo Sahin, Production Design – Josephine Ford. Production Company – Lava Bear Films/Porchlight Films/Yoki/Blue Tongue Films/Screen Australia.

Cast

Guy Pearce (Eric), Robert Pattinson (Rey), Susan Prior (Dorothy Peeples), Scoot McNairy (Henry), David Field (Archie), Tawanda Manyimo (Caleb), Anthony Hayes (Sergeant Rickofferson), Gillian Jones (Grandma), Jamie Fallon (Colin)

Plot

The Australian Outback, ten years after the collapse. Eric stops by a bar in the desert only for three men fleeing from a robbery gone wrong to crash in their vehicle just outside. Unable to get their truck restarted, they steal Eric’s car. Eric takes their truck and pursues to get his car back only for it to end in a roadside confrontation where they pull guns and beat him unconscious. Eric then encounters Rey, the slow-witted brother of Henry, one of the men who took his car, who was left behind in the getaway, thought dead. He drags Rey to a doctor to patch him together and then sets out on the road to follow the three men. As they journey to Karloon where Rey knows that his brother Henry is going to be, a slow friendship grows between Eric and Rey. Together, this pits them against the dangers encountered on the road and the people pursuing Eric.

Okay, so the title needs some work. It makes you think firstly that we are in for a dog film – which, given the film’s enigmatic final scene, may well have been intentional – or perhaps something about a wandering minstrel viz The Irish Rovers. One even held out the possibility just from a reading of the title that we are in for a film based around the Mars Rover. None of which really keys you into what the film you are about to watch is about. Even a glance through the plot description from the press release gives more the impression that we are watching a revenge/road movie perhaps something like the recent Out of the Furnace (2013).

Of course, the bit that then gets your attention after reading the press materials is the film’s setting of ‘ten years after the collapse’. Exactly what has collapsed is never specified, although the impression we get is that they are talking about economic collapse and social cohesion as the world we seem to be in is one where people are either making do with American dollars as currency or else make comments about how money is now useless paper. This recalls the other Australian classic Mad Max 2 (1981) with its images of a burned-out post-collapse future world where people are eking out a desperate survival on the remnants of the present.

Perhaps even more so than that, we come the closest to the original Mad Max (1979), a very different film to its sequels, one set in a burned-out (but not post-holocaust) near future where the law was starting to fray at the edges as we follow the tough Main Force Patrol in their efforts to stay atop the anarchy. The Rover comes without the MFP – or rather, they are there in the person of soldiers who turn up occasionally – but it often feels like it could be taking place in the same near-future Australia. Indeed, when you think about it, Guy Pearce’s Eric and Mel Gibson’s Max would make for rather fascinating nemeses if paired up against one another in a film.

You are taken aback at what David Michôd does with the film. The landscape is the bare, wide open Outback that we are familiar with in any Australian film from Walkabout (1970) to Wake in Fear (1971), The Proposition (2006), Tracks (2013) and the Mad Max, Crocodile Dundee and Wolf Creek films – a world that seems to almost dwarf the human ability to grasp it, where the normal rules of civilisation start to collapse at the edges and it seems to require a special breed of men who can live in it.

David Michôd makes a darkly nihilistic film, one about survival in a collapsing world. The casualness of the violence – just the way Guy Pearce picks up the gun the dwarf merchant’s offers him and shoots him with it – is astonishing in its nonchalance. You are reminded of something like a Sam Peckinpah Western – the plot after all could easily be transplanted to work as a Western – alhough Michôd is less interested in the glorification of the violence or of the way in which the world is a Hemingway-esque crucible of men’s values that Peckinpah was.

In fact, what The Rover reminds of more than anything is the books of Cormac McCarthy, author of works like Blood Meridian, or the Evening Redness in the West (1985), No Country for Old Men (2005) and The Road (2006). Both create often very violent stories but, like McCarthy, David Michôd is less interested in action and the spectacle of violence than the interior spaces of the protagonists in harsh and violent worlds. Like McCarthy, the dialogue is extraordinarily evocative in its terseness. There are some exceptionally written passages – especially one scene where Guy Pearce talks about his past and the murder of his wife to the soldier (Anthony Hayes) who has him prisoner. Like McCarthy, Michôd is concerned with morality – for McCarthy, questions of what is human and right, of his characters believing in an almost Old Testament sense of judgement; for Michôd, the central question of what matters in a world where morality is collapsing at the edges, where a man can murder his own unfaithful wife and her lover and walk away without any repercussions except the guilt that continues inside his own head. You could call it the soul of the Mad Max films.

Guy Pearce is an actor who has this kind of tightly bound, internalised character down to a degree of expertise such that he can slip into the role by second nature. It is easily a part that could have with a few slight adjustments turned into a cliched revenge-seeking action hero. The journey of the film is a road movie standard – of two mismatched characters coming to care about one another. Or perhaps even more so an Of Mice and Men (1939) friendship.

The other half of the relationship is surprisingly cast with Robert Pattinson. Ever since he came to fame as a teen idol in Twilight (2008) and sequels, Pattinson has been busily doing what Johnny Depp did in the early 1990s and run in the opposite direction and determined to prove himself as a serious actor, working with the likes of Werner Herzog in Queen of the Desert (2014), Anton Corbijn in Life (2015), Claire Denis in High Life (2018), Robert Eggers in The Lighthouse (2019), not to mention with David Cronenberg twice in Cosmopolis (2012) and Maps to the Stars (2014) – directors that all come with strong followings in arthouse release rather than the multiplex. Pattinson goes the Full Retard here – in the sort of role of the imbecilic halfwit and/or socially maladjusted loner filled with awkward tics that actors like Giovanni Ribisi and Jeremy Davies used to specialise in – and gives a surprisingly solid performance such that one tends to forget that it is Pattinson acting and engage with the character’s simplicity.

David Michôd had previously directed the crime film Animal Kingdom (2010) and subsequently went onto the Brad Pitt modern war satire War Machine (2017) and the historical film The King (2019). His co-writer Joel Edgerton is better known as an actor including as the young Owen Lars in the Star Wars prequels and other films like The Thing (2011), The Great Gatsby (2013) and Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014), while he subsequently made his directorial debut with the horror film The Gift (2015).

(Winner in this site’s Top 10 Films of 2014 list. Nominee for Best Director (David Michôd), Best Original Screenplay, Best Actor (Robert Pattinson) and Best Actor (Guy Pearce) at this site’s Best of 2014 Awards).

Trailer here