New Zealand. 1977.

Crew

Director/Producer – Roger Donaldson, Screenplay – Arthur Baysting & Ian Mune, Based on the Novel Smith’s Dream by Karl [C.K.] Stead, Photography – Michael Seresin, Music – Mathew Brown, David Calder & Murray Grindlay, Special Effects – Geoff Murphy, Art Direction – Roger Donaldson & Ian Mune. Production Company – Aardvark Films.

Cast

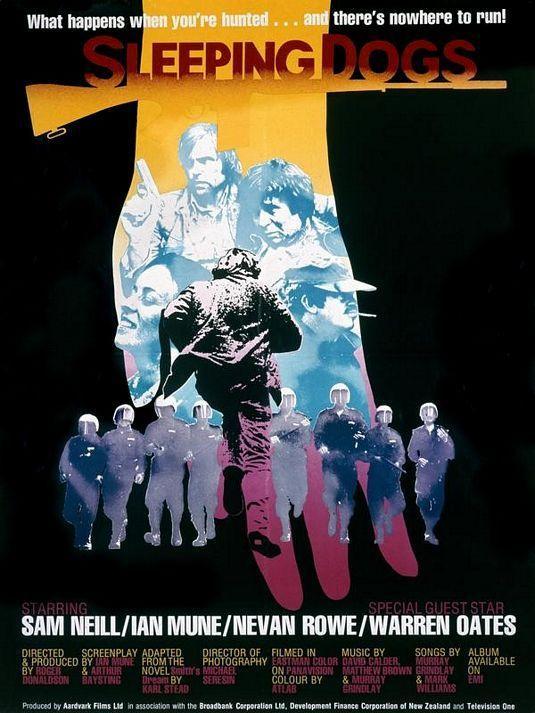

Sam Neill (Smith), Ian Mune (Bullen), Warren Oates (Colonel Willoughby), Nevan Rowe (Gloria Smith), Donna Akersten (Mary), Clyde Scott (Jesperson), Ian Watkin (Dudley), Don Selwyn (Taupiri), Davina Whitehouse (Elsie Thompson), Bernard Kearns (Prime Minister Vorster)

Plot

After learning that his wife has started seeing another man, Smith gets up one day and leaves her, his daughter and home and rents a bach on an uninhabited island off the Coromandel Peninsula. At the same time, Prime Minister Vorster declares martial law in New Zealand. A resistance movement springs up. Smith’s idyll on the island is shattered when he finds a cache of arms left by the resistance and is then arrested as a subversive. Jailed, he is offered the opportunity to make a televised confession and go into exile or else face execution. Instead, Smith manages to escape. He flees across the country hunted by the government’s armed Specials, where he reluctantly becomes involved with the resistance.

I grew up in New Zealand. It is a country that has around the same landmass as the United Kingdom, yet only a population that topped four million in the last decade. The country’s filmic output is negligible – maybe 3-4 films per year and television production limited to a single teen soap opera Shortland Street (1992– ), plus maybe a sitcom and one dramatic series produced a year.

Certainly, for such a minuscule output, the country’s film industry has had some surprising success stories in the international arena – directors like Vincent Ward of The Navigator: A Mediaeval Odyssey (1988) and What Dreams May Come (1988), Peter Jackson of The Lord of the Rings fame, Lee Tamahori of Die Another Day (2002), Jane Campion who made The Piano (1993) and In the Cut (2003), Martin Campbell who made GoldenEye (1995) and Casino Royale (2006), and actors such as Russell Crowe, Lucy Lawless, Kerry Fox, Anna Paquin, Temuera Morrison, Keisha Castle-Hughes, Karl Urban and the late Bruno Lawrence.

Of course, Sleeping Dogs introduced two major talents that would go onto great success internationally – actor Sam Neill in his first screen performance and director Roger Donaldson (see below for his other credits). It was NZ’s second ever science-fiction film – the first feature-length one – with that distinction being held by the now lost A Message from Mars (1903).

Sleeping Dogs was the cornerstone of the New Zealand film industry. It is hard to believe in the same year that also produced Star Wars (1977) that the total output of New Zealand feature films up to that point could be counted on one hand and a couple of fingers. As Sam Neill points out in his excellent documentary Cinema of Unease: A Personal Journey by Sam Neill (1995), the New Zealand cultural image was (and to a large extent still is) determined by foreign influences, first as colony of England and mostly through the overwhelming prevalence of American films and television. As Neill notes, it was strange going to local cinema screens when he was growing up and seeing only international faces and accents reflected back.

With Sleeping Dogs, all of that changed. Sleeping Dogs was the first film to be a major home-made Kiwi success. It saw a local director relentlessly incorporating international styles of filmmaking. Most importantly though, it was local accents and locales being seen up on screen. The success of Sleeping Dogs directly led to the setting up of the New Zealand Film Commission the same year – a government-funded body that both finances local filmmaking and acts as an international sales agent.

The success that Sleeping Dogs had was in the shock image of the country it reflected back. To such a placid and dull country as New Zealand, where police today still don’t carry guns and the national crime rate barely runs above half-a-dozen murders a year, the sense for audiences in 1977 in seeing all of that overrun by the imagery of fascism – helmeted riot squads beating up mobs with batons in the street, i.d. cards for citizens, armed resistance movements, arrest without due process – must have had an electrifying shock effect. The film’s world is a nightmare that is very peculiar to New Zealand in the late 1970s – one in which the country is rent by union strikes, Mideast oil shortages and petrol rationing (this was the infamous era of government induced Carless Days in an attempt to cut petrol consumption). A further sense of immediacy, that this really was happening, is reinforced by the image of Dougal Stevenson as a newsreader on tv screens, a role that Stevenson also conducted in real life on the then sole nightly news broadcast on one of the country’s two tv channels.

The scary thing about Sleeping Dogs was how prophetic such imagery was as only a matter of years later (1981) would see the very same images of helmeted police battering crowds with batons in the streets during the nationwide protests against the Springbok rugby tour. The most noticeable thing is that when Sleeping Dogs was released internationally it did zero business – there it was what it just a standard issue dystopia-come-action film – whereas back home in New Zealand all the resonance was in the sense of familiarity being overturned.

Actor and later director Ian Mune – see Bridge to Nowhere (1986) – adapted Smith’s Dream (1971), a novel by C.K. Stead, who is nowadays regarded as one of the country’s most acclaimed literary figures. The film fairly much strips away all of Stead’s sociopolitical writing and turns the story into an action film. Sleeping Dogs has no further ambition beyond this. Certainly, it never engages in any of the political/ideological diatribe that dystopian science-fiction does – the government portrayed is just totalitarian and repressive, a generic police state with no greater depth than that. We never even find out what stance the rebels are fighting for.

Roger Donaldson, who was operating on a shoestring budget, keeps the action moving. The best scenes in the film are the last twenty minutes or so with Sam Neill and Ian Mune struggling through the bush hunted by the Specials with Neill having to drag a wounded Mune. Here Donaldson evokes a gritty harsh survivalism. The climactic scenes with they getting to freedom on the other side of the bush only to find themselves surrounded where Sam Neill realises that rather than surrender, his only choice to defy the regime is to start shooting is great stuff.

The film is probably too laidback and tends to drag somewhat in between the action scenes. Here though Donaldson adds an appealingly laidback parochialism. Where most dystopian films tend to create heroes as ideological cutouts, Donaldson keeps the film focused on the wry warmth of his characters. Smith is shown as just an ordinary man in naturalistic surroundings – playing with the dog on a beach, cycling through the countryside, mowing the lawns at the motel. After all, how more archetypically average could you get than a hero who is known as just Smith? As such, Smith is the quintessential New Zealand hero. He seems to embody all the aspects that the country saw as laudable around that era – the time when New Zealand was sitting just between post-War British colonialism and modern metropolitanisation – Smith is happy-go-lucky, disinterested in any ideological stance on the world around him and at best rises to an anti-authoritarian defiance, but mostly just wants to be on his own and enjoying Godzone.

Sam Neill has yet to fully develop the charisma that had labeled the Sexiest Man in the World in the 1990s. A couple of years later, Neill would appear in My Brilliant Career (1979) then go onto The Final Conflict (1981) and the international acclaim of the masterful tv series Reilly, Ace of Spies (1983), directed by fellow New Zealander Martin Campbell, and the rest is history. Here Neill is still new as a screen presence – even though he is the hero of the show, his Smith is a passive character, yet Neill has an undeniably cocky and infectious smile that signals great screen presence.

The craggy Ian Mune is good as the roughnecked Bullen. Even before the habit of bringing American stars in to carry films in the international arena became commonplace in NZ, Donaldson was way ahead of the crowd and imports Warren Oates in an appearance as an American military officer. The early parts of the film are stolen by Don Selwyn in a brief appearance as a Maori man who rents Sam Neill the island and gives him a dog – “What’s its name?” “I don’t know. It’s your dog.”

Sleeping Dogs should not be confused with the Canadian science-fiction/heist film Sleeping Dogs (1998).

Roger Donaldson next made Smash Palace (1981), a disturbing and emotionally raw film about a marriage breakup, which is one of finest films to emerge out of New Zealand in the 1980s and remains Donaldson’s single best film. The success of Smash Palace took Donaldson overseas where he made The Bounty (1984) and the Kevin Costner thriller No Way Out (1987), before such generally unexceptional mainstream commercial output as Cocktail (1988), Cadillac Man (1990), White Sands (1995), the underrated remake of The Getaway (1994), the disaster movie Dante’s Peak (1997), Thirteen Days (2000), before returning to New Zealand to make The World’s Fastest Indian (2005), and then back to international work on The Bank Job (2008), Seeking Justice (2011) and The November Man (2014). Donaldson’s one other venture into the science-fiction genre so far has been Species (1995).

Trailer here